Detachment Alpha of Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2 aboard the USNS Catawba with the USS Cole and the MV Blue Marlin in the background. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

On the morning of Oct. 13, 2000, Chief Warrant Officer Frank Perna and his team of US Navy divers were sipping cappuccinos at an open-air coffee shop, enjoying a beautiful Italian morning in the Port of Bari, when the distinct ringtone of Perna’s cell phone cut the casual banter and light mood.

The divers, deployed with Detachment Alpha of Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2 aboard the USNS Mohawk, turned their attention to their officer in charge as he picked up the phone and listened intently. Mike Shields, now a retired master chief master diver, could tell the call was serious.

“I understand,” Perna said into the phone before hanging up. “We will be ready.”

Less than 24 hours earlier, the USS Cole, a US Navy guided-missile destroyer, was docked in Yemen’s Aden harbor for a planned refueling when al Qaeda suicide bombers in a small boat packed with at least 400 pounds of explosives steered their craft into the Cole’s left side. The blast ripped a 1,600-square-foot hole in its hull, killing 17 American sailors and wounding 39.

Aqueous Film Forming Foam flame retardant floats on top of the water, preventing any fuel from igniting near the damaged left-side hull of the USS Cole in October 2000. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

A skilled diver with extensive experience in underwater salvage and recovery operations, Perna had worked on several high-profile dive operations. He participated in salvage and recovery operations for Trans World Airlines Flight 800 and the USS Arthur W. Radford after its collision at sea with a Saudi Arabian container vessel.

Perna looked up at his team, who stared back with anticipation.

“The USS Cole was damaged from an explosion while in port,” he told them. “We are going to Yemen to assist the crew in recovery and salvage of the ship.”

The 12 men who composed Detachment Alpha launched into planning and preparing for a daunting mission: They would locate missing sailors, assist in stabilizing the ship, recover evidence, and perform structural inspections of the Cole after a terrorist attack.

“We immediately started pulling resources and gear to support several different diving and salvage scenarios,” Shields told Coffee or Die Magazine recently. “Because we were going to be somewhat isolated in Yemen, we knew everything we brought had to serve several purposes.”

The USS Cole (DDG-67) is towed by the Navy tug vessel USNS Catawba to a staging point in the Yemeni harbor of Aden to await transportation by the Norwegian-owned, semi-submersible heavy-lift ship MV Blue Marlin. US Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Don L. Maes.

The next day, the hand-picked team of Navy divers landed in Yemen with all the necessary dive systems to support the numerous planned and unplanned tasks of diving into and under a critically damaged ship. They loaded their gear onto two flatbed trucks and departed the airport with a sketchy Yemeni military escort. As they passed through several military checkpoints, Perna and his team began to feel the gravity of the situation.

When they arrived at the port, most of the team went to work setting up gear and readying a dive site near the ship while Perna and his senior leaders went to assess the damage. The sight shocked them. The ship was blackened by the explosion, listing slightly to the left, and without electrical power. The only light was from the green glow of the pier lights.

“Our first glimpse of the ship that night will be forever fixed in our minds,” Perna told Coffee or Die.

As Shields took in the damage and saw the Cole’s battle-weary crew members sleeping on mattresses scattered randomly on the ship’s weather decks, his shock turned into determination.

Sailors from the USS Cole rest on the helicopter deck in Yemen, Oct. 13, 2000, the day after a suicide bomber attacked the ship in the port of Aden, Yemen. US Navy photo by Jim Watson.

“Get in the water,” he thought. “Get the Cole back.”

On the morning of Oct. 15, 2000, the divers began the first phase of their mission. Several sailors were still missing in the flooded spaces below, and the men of Alpha Detachment had to get them out and repair or salvage what they could as soon as possible.

With flooding in the ship still posing a significant threat to electrical and engineering spaces, time was not on Alpha’s side. They determined which areas of the ship to search, identified a centralized location to set up a dive station, and planned how to safely enter the spaces they needed to reach. They boarded the Cole, set up gear, and began diving from inside the flooded spaces.

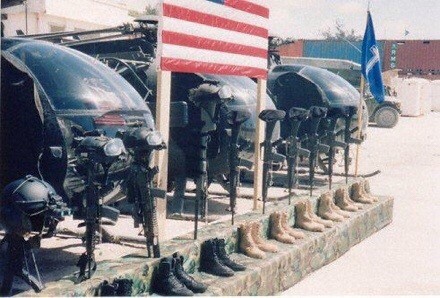

With the utmost care and respect, the Navy divers recovered missing Cole sailors. When a sailor was recovered, the divers paused their work to observe a moment of silence and honor the dead. They draped a flag over each fallen soul and escorted them down the pier to be taken back home.

“It’s a very heavy feeling in your heart to see one of your own covered in the flag,” Perna said. “It’s hard to check your emotions and refocus attention back to the task at hand, but you’ve got to push it back down because we’re doing a dangerous job.”

Gunner’s mate Petty Officer 2nd Class Don Schappert prepares to enter the lower levels of the flooded engine room assisted by hull maintenance technician Petty Officer 2nd Class Brett Husbeck. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

In addition to recovering the fallen, Alpha had to stop the flooding into the only engine room that was still operational. Reaching the damaged area required navigating through 50 feet of razor-sharp mangled steel, reduced visibility, and a thick layer of engine fuel building on the surface of the water. To get in and out of the water, the Navy divers had to travel through a layer of oil that they worried might catch fire if something sparked. The team deployed a fire retardant over the surface as a preventive measure.

Shields, who was familiar with the layout of the Cole from conducting routine maintenance on the ship the previous year, was one of two divers who suited up, went below the surface through an auxiliary shaft, and made their way slowly to the engine room. They couldn’t see anything and kept bumping into loose gear and debris floating around the spaces.

Making things even worse, the divers’ life-giving tether lines of air, communication, and light power — their “umbilicals” — were constantly hanging up or snagging on unknown obstructions. With every valuable foot gained, the divers had to stop to free themselves.

“We were blindly feeling around for landmarks that would take us to where we thought the flooding was coming from,” Shields recalled.

Using memories of what the engine room would have looked like, Shields and his dive buddy felt around and found landmarks to orient themselves by, eventually finding the cause of the flooding. They filled it with a 3-inch braided ship’s mooring line covered in a thick layer of electrical putty.

“We filled in the crack and effectively stopped all flooding,” Shields said.

Stopping the flooding saved the ship from sinking and prevented what could have been a total loss.

Mike Shields descends into a flooded engine room through a ventilation shaft on the USS Cole in October 2000. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

The next day, the Cole’s diesel generator stopped running, and members of the dive team had to locate and secure the damaged piping and reroute pressure through alternate channels back to the generators. Navigating underwater in the damaged area again proved challenging. Bulkheads were blown inward, all non-watertight doors had broken from their hinges, filing cabinets lay scattered across the deck, and visibility was reduced to less than 3 inches.

The Navy divers spent a lot of time rerouting valves controlling pressure, fuel, oil, or air to their secondary and tertiary systems to help offset the ship’s left-side listing. With the major flooding stopped and the Cole stable, the team focused on reviewing and assessing the massive opening the blast had ripped in the left side of the ship’s hull.

“It was nothing less than devastating,” Perna said. “The most disturbing sight was the extensive damage inside the ship. The blast from the explosion had torn 30-35 feet into the center of the ship.”

The explosion was so powerful that the deck had blown upward and fused onto the bulkhead where an office once sat. Crew members who’d been eating on the mess decks reported that the blast’s power created a visible wave that traveled across the deck.

The divers created a staging area just aft of the blast area on the Cole’s left side so they could easily access the outside space and assist the FBI and several other agencies in gathering information and documenting evidence for future investigations.

Hull maintenance technician Petty Officer 2nd Class Brett Husbeck, left, and engineman Petty Officer 2nd Class Mike Shields, right, conduct dive operations in a flooded engine on the USS Cole. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

Outfitted with thick rubber wetsuits, dive knives, and iconic yellow Kirby Morgan MK 21 diving helmets, divers splashed into the hot Persian Gulf water and entered the blast area.

“Everything was surreal about diving on board and into a ship with an extensive hole in the side of its hull,” Perna said. “The fact that you can dive inside the ship, turn around, and see the sunlight cascading into the enormous space is beyond explanation.”

On Oct. 17, 2000, Navy divers prepared to search the flooded main engine room, which suffered extensive damage in the blast and was essentially a total loss. Confirming primary and secondary routes with engineers and the crew, Perna and his team devised a plan to move through the ship’s ventilation-shaft system to access the previously unreachable space.

Before entering the cramped shaft, divers wrapped fire hoses around their umbilicals for protection, modified their gear to slim down their profiles, and slipped into wetsuits to protect themselves from the environmental hazards of fuel, oil, and razor-blade-like steel. The divers inched their way to the main engine room, a feat Perna and Shields likened to John McClane crawling through the ventilation shafts of Nakatomi Plaza in Die Hard.

Damage to the USS Cole. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

Watching closed-circuit video systems, engineers from the Cole and the USS Donald Cook guided the Navy divers as they moved through sheared bulkheads, buckled decks, broken pipes, and wires that created an immense “spider web” of destruction. Metal shavings sparkled as the divers’ lights scanned the engine room.

“We could feel the change in densities between fuel and water,” Perna recalled. “Everything fouled our umbilicals in the engine room. Pieces of broken equipment fell from the overhead as we disturbed their delicate balance.”

In that unforgiving, stifling space, the men of Detachment Alpha recovered three more missing sailors.

Over the following 10 days, from Oct. 18 through Oct. 28, the Navy divers recovered personal items from the flooded spaces and sifted through the fine sand on the seafloor for anything that might have belonged to the fallen. They searched every flooded compartment, including areas deemed too dangerous to enter safely, recovering all remaining missing sailors and assisting FBI investigators in collecting evidence. The divers inspected every inch of the blast area, looking for evidence of the explosive device. The FBI was keenly interested in anything that might help its investigation to identify the terrorists or the composition of the bomb.

A diver descends a ladder in the flooded engine room. Photo courtesy of Mike Shields.

The Navy divers also worked to mend damaged areas of the Cole and helped prepare the ship for its journey back to the United States. They relieved pressure in the main structural supports by drilling holes at the ends of the significant cracks, alleviating stress and preventing the damage from spreading. Once the necessary repairs were made, the team prepped the ship for a journey out to sea.

The challenge was to keep the ship from listing over to the left side. The Cole’s crew worried that the repairs made to stop the flooding might be damaged once in the open ocean.

“We had the idea to hedge our bets and have some contingencies in place if something happened,” Shields said.

The USS Cole is towed from the port of Aden, Yemen. Photo courtesy of the US Navy.

They ran several hydraulic pumps to the critical spaces and had discharge lines over the side in case a space started to fill with water.

On Oct. 29, the USS Cole slowly moved away from the pier with a small crew aboard to monitor the ship. Supported by tugboats and a tow line from the USNS Catawba, the Cole made the journey from the coast of Yemen to the MV Blue Marlin, a 700-foot-long Norwegian heavy-lift transport ship 23 miles out at sea.

When the Cole reached the Blue Marlin, the Blue Marlin partially submerged its lower deck and floated it under the damaged Cole. Once in place, the ship slowly rose to the surface, gently lifting the Cole from the ocean and resting the mighty ship on the Blue Marlin’s deck.

The MV Blue Marlin transports the USS Cole from Yemen following the attack on the ship in 2000. Photo courtesy of the US Navy.

With the Cole on the Blue Marlin, Shields and his divers checked the ship for flooding once more and found that their work had held. Shields gave the thumbs-up to higher, climbed the side railing, and dove into the ocean, swimming back to his team on the Catawba.

The entire docking evolution took nearly 24 hours to complete. With the Cole securely aboard the Blue Marlin’s deck, they made the trip back to the United States.

The Navy divers’ contributions were instrumental, Perna said. In a small amount of time, the team got the diesel generator back online, rerouted the ship’s air system, set up and operated emergency dewatering equipment, and provided air recharging service to the FBI and explosive ordnance disposal divers.

The guided-missile destroyer USS Cole arrives for a scheduled port visit to Souda Bay, Greece, July 19, 2012. The Cole, home-ported at Naval Station Norfolk, is on a scheduled deployment and is operating in the US 6th Fleet area of responsibility. US Navy photo by Paul Farley.

“No one person can accomplish them alone,” Perna said. “I was grateful to have such a fine and experienced diving and salvage team. I am indebted to and extremely proud of the divers in Detachment Alpha who made it all possible.”

The Detachment Alpha divers safely conducted 37 dives with more than 76 hours of subsurface work during the Cole operation. The ship was fully restored to service within 18 months of the attack in Yemen. The men of Detachment Alpha played a vital role in the operation that ensured the USS Cole’s ability to sail freely today.

A US sailor visits the USS Cole Memorial on the 18th anniversary of the terrorist attack on the ship. Seventeen sailors were killed, and another 39 were wounded in the attack. US Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Justin Wolpert.

The Men of Detachment Alpha:

CWO3 Frank Perna

ENCS (MDV/SG) Lyle Becker

BMC (SW/DV) David Hunter

ETC (SG/DV) Terry Breaux

HMC (DV) Don Adams

HT2 (DV) Don Husbeck

GM2 (SS/DV) Roger Ziliak

STG2 (SW/DV) Donald Schappert

IS3 (DV) Greg Sutherland

EN2 (DV) Mike Shields

BM2 (DV) Mike Allison

GM3 (DV) Sean Baker

This is reposted with permission from Jayme Pastoric