At the end of Part 2, I had taken command of F Company of the Training Group’s 1st Battalion at Camp Mackall, NC. For those that do not know, Mackall is a small installation, occupied by elements of the Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS) about 30 miles west of Fort Bragg. It is home to several components of the Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC). At the time, F Company ran 2 Phases of the SFQC. One (Phase II), focused on land navigation and small unit tactics and the other (Phase IV), conducted Unconventional Warfare training and the culminating Robin Sage Exercise. I was living the dream and enjoyed every day of that assignment. Of course, the Army’s personnel management system has the mission to make sure that nothing good ever lasts long.

It started indirectly. Although I had not known him before, I got along very well with the Battalion Commander (BC) who had hired me. As luck would have it, he came out on a Special Mission Unit (SMU) Command List shortly after I took command – and he was gone. It was a great opportunity for him – but turned out not so good for me. Another Lieutenant Colonel was activated off the Alternate Command List to take the Battalion. As it happens, he and I had been Majors together in 3rd Group (96-98), although I did not know him well. The mission at Mackall was clear for my cadre and me; however, as I wrote in an earlier article, there were many ill-conceived initiatives for the SFQC being considered at SWCS during this period. I quickly found out that my new BC and I were philosophically on opposite sides of these plans. That naturally led to friction between us. Moreover, as often happens in these situations, that friction eventually evolved into one of those annoying ethical dilemmas I have written about ad nauseam.

Long story short, in May of 2001, I was Relieved of Command by that BC, a.k.a. fired, sacked, dismissed. However, since that episode is convoluted and not germane to the subject at hand, I will save that part of the story for another time. Suffice to say, getting fired is considered a sub-optimum outcome to any assignment. That is also how I became personas non grata at the Training Group and, indeed, all of SWCS for the second time. I spent the next few months fighting the accusations made against me to justify my firing. I will mention just one here because it is the only accusation that was based on a kernel of truth. Allegedly, I had been “insubordinate” to the BC. For what it is worth, I have found that it is all but impossible to tell your boss something he really, really does not want to hear without him perceiving it as insubordination.

As a practical matter, there is an administrative process to appeal those sorts of negative personnel actions and I took immediate advantage of that mechanism. Bottom line, I made my case to the Army and achieved a partial vindication in a matter of 9 months or so. I received my promotion orders to Lieutenant Colonel in March 2002, backdated with an effective date of 1 January of that year. I purposely held my promotion ceremony in front of the Bull Simon statue across from the SWCS HQ. Then Brigadier General Stanley McChrystal did the honors. He was one of those SF qualified infantrymen I mentioned in Part 1. As he put the rank on my collar, he asked me, “Terry, is it true that you commanded three SF Companies?” I replied, “Yes Sir, twice successfully!” We all got a chuckle out of that.

That was not the end of the story; I also had to spend a considerable amount of money to hire lawyers who spent years getting the associated “bad paper” removed from my records. Oddly enough, that was not my biggest career management problem going forward. With my promotion orders came a letter from Department of the Army (DA). The letter stated that since I had more than 24 years of combined service I was ineligible to be considered for War College attendance. In effect, I was non-select for the school before I even pinned on that silver oak leaf. In turn, that meant that I was instantly non-competitive for Battalion Command or promotion to Colonel. Unfortunately, there was no waiver or appeal process for that verdict – and, yes, I looked.

However, in the interim, 9/11 happened and I had little time to dwell on it myself. I wanted to get into the fight ASAP. For that first few months, I was in assignment limbo at Fort Bragg. SF Branch wanted nothing to do with me and DA was indifferent. I came to realize that essentially I had been ejected from the system. I had not jumped ship, I had been pushed off. That was fine with me. I still knew a lot of people and started doing my own independent talent management. The pattern for the next 9 years went like this. I would call commanders I knew directly, or have a mutual friend introduce us and ask for work. I was not often rejected. I did a number of jobs: J3 (Operations), J5 (Plans), Chief of Staff, and Deputy Commander for example. Additionally, I did Liaison work between HQs on occasion and even commanded a couple of ad hoc organizations in theater.

I do not want to exaggerate my contributions to the mission. I am not pretending to be a hero. I took my share of risks, but I have no medals for valor or purple hearts. Nevertheless, I carried my share of the burden and then some. I am proud of that. The reasons I was able to do that for an extended period are directly related to the idiosyncrasies built into the current personnel management system. First, because I was a “free agent,” I could go where I pleased and no one at DA or SF Branch cared – or interfered. Second, the system was consistently failing commanders in the field. Almost everyone else was “locked” into his or her current assignment and even the system itself had no pre-existing mechanism to meet fluctuating personnel demands from the field commanders. Never mind “talent management,” there is something fundamentally wrong with a system that has to ignore its own rules to even try to support the warfighter. The result was that commanders – by necessity – had to make off the books “handshake deals” with their peers who were not deploying for critical manpower fills.

It was a heck of a way to run a railroad. Still, it worked for me for a long time. Of course, the system could not abide that sort of autonomous freedom of action indefinitely. Toward the end, I was involved in planning for the drawdown of all SOF in Iraq. In February 2011, I had briefed the plan for approval to all the senior leadership in the theater and beyond. Afterwards, I decided to take some down time back at Bragg with my wife. That is when SF Branch sprung their ambush. About 10 days after I got home they hit me with a “Request for Orders” (RFO) sending me to a Branch Immaterial (BI) assignment with the 8th Army HQ in Korea. BI simply means that the job required only a warm body to move papers. As usual with the system, my training, expertise, experience, and / or “talent” was entirely irrelevant to the job parameters.

To be certain, I could have dodged this RFO. Technically, I was “on leave” and could have got on the first thing smoking back to Iraq. The 1-Star Commander of the HQ I had been working for had asked me to come back as soon as felt like it anyway. I doubt that Branch would have even tried to “extradite” me out of theater. That is why they did not drop the RFO earlier. I also could have gone to a number of 3 or 4-Stars I had worked for and asked for a favor. I did not do either. My last boss in Iraq in 2011 was a Colonel (O-6) who had worked for me as a Major in 2004. One of my peers had already pinned on his first star and another was about to. I did not envy their success, but all were glaring reminders that professionally I was just treading water. Objectively, I had done all that I could do and then some from outside the system. And, just as obviously, the system saw no further value in me. I did not leave because I was tired, disillusioned, or discouraged but I also had no interest in just killing time. Therefore, I came to the conclusion that while I was still having fun and did not want it to end, just as clearly, it was the right time to go.

So I told SF Branch to find someone else and I dropped my retirement packet. Frankly, I do not think they cared. I believe that they offered that crap job as my one and only assignment option because they wanted to force me out. I may not be anyone special, but I am not Joe Shit the Ragman either. I thought that it was insulting and told them so. They certainly made no effort to dissuade me from leaving. They were convinced that I was “excess to the Regiment’s requirements” and needed to go. The sooner the better as far as the system was concerned. The funny thing is that when someone takes retirement “in lieu of PCS,” DA does not let you quit honorably; rather, they make it abundantly clear that that you are being fired as punishment for your transgression. In other words, after 36 years of mostly exemplary service, DA itself declared me persona non grata! Somehow, that seems entirely appropriate.

In terms of military careers, in typical American style, today we have made promotions (and the resulting pay raises) the single measure of professional success. You either get promoted on a strict timetable or you are forced out. No matter how good you are in your current job, you must always keep moving with the herd. Therefore, the system persists in pounding ill-fitting human pegs into holes they are not suited for to temporarily fill spaces. And, I do mean temporarily. In a year or so we pull out all of the pegs and start pounding every one of them into new holes! In the process we disillusion far too many and they vote with their feet and leave. How exactly does a personnel system that facilitates and perpetuates high turnover help sustain unit combat readiness? It does not. That does not make much sense today. I would argue that it never did, and it is past time to overhaul our system.

I submit that the current system is actually optimized not to retain talent, but rather to deprive the Army of soldiers and officers – just as they are seasoned enough to be of real value to a unit. In effect, the system is fratricidal and designed to encourage the majority of our junior officer and NCO leaders to self-select out at the end of their initial contracts. In turn, we spend enormous time, money, and effort, bringing newer people into the front end of the pipeline to replace our loses. There is no real logic or military necessity that drives this dysfunctional methodology. We allow that nonsense to continue simple because that is the way we have always done it – at least since WWII. If an enemy had such a devastating casualty producing capability, we would be working tirelessly on an effective countermeasure. We certainly must stop doing it to ourselves – and soon.

Managing talent effectively takes more effort than what we are doing now. To make the best blades, you have to hammer the steel. The harder the metal, the more you have to hammer. It takes extra work, but those harder heads – if hammered properly by a good leader – often make great soldiers. I was lucky that some good leaders took the time and effort to hammer me. Here are some of the old-fashioned mallets used successfully on me over the course of my career. Rehabilitative transfers, “acting” rank (call it a test run), and Article 15s – used old school style to punish, educate and shape, not to terminate. Leaders must be provided these kinds of tools if talent management is ever going to be a reality. True talent cannot and will not be centrally managed and mass-produced by DA. Rather, it must be handcrafted by the individual soldiers themselves and their leaders at the lowest levels. The Army must push down the right tools and authorities to them and would be better served by removing the bulk of those “personnel management” responsibilities and decisions from PERSCOM.

Epilog: one of the foreseeable consequences of having been rogue for almost a decade is that I did not really belong to anyone at Fort Bragg. SF Command and later USASOC had carried me as “excess” on the books for that entire time. The HQ G1s had kept accountability of me, but none of the Staff Directorates owned or owed me. Therefore, there was no one obliged to even consider putting me in for an end of service award or to sponsor a retirement ceremony of some kind. Therefore, it is no surprise that I got neither. When I signed out on my last duty day in the Army, one of the Specialists at HHC USASOC gave me a folded American flag in a triangular display case and thanked me for my service. I thanked her back and left. I must say, it was an anticlimactic conclusion to a professional career I consider very well spent. Moreover, I will not deny, I thought the occasion was fully deserving of a wee bit more pomp and circumstance.

I did have one last “official” duty to perform. Two days after my retirement date, I returned to Camp Mackall one last time to take a student team’s Robin Sage Briefback. After interacting with the students, I sat down with a couple of the Cadre Team Sergeants and reminisced about the Q-Course for an hour or so. Although I did not remember him, one of the NCOs had gone through the course when I had been out there. It was a pleasant afternoon. Of course, I had to eventually let them get back to work; so, I said my goodbyes and headed home. Although I was driving east and it was mid-afternoon, I had no doubt that I was riding into the sunset. That is, after all, exactly the way a story like this is supposed to end. De Oppresso Liber!

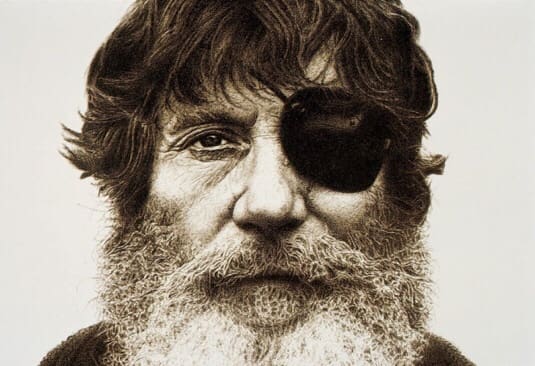

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.