The Army’s continuous transformation efforts in 2024 centered on the service’s network of systems.

Army leaders have turned to Soldiers to give comprehensive feedback on how to improve its systems and command and control and communications

During the initiative, the service incorporates new technology into operational exercises to better evaluate the equipment’s’ effectiveness in Army formations. The service has consciously built toward its next iteration of Project Convergence, a joint multi-national, multidomain series of experiments.

Year of change for 101st

The Soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, have played a pivotal role in executing the Army’s modernization concept, “transforming in contact,” developed by Army Chief of Staff Gen. Randy A. George.

Troops at the division’s command post now operate network structure that the service once assigned to the brigade level.

Soldiers used the first Integrated Tactical Network aerial toolkit during Operation Lethal Eagle in April and during a Joint Rotation Training Center in January.

During Lethal Eagle, Soldiers engaged in long-range, large-scale, air assault operations or L2A2. During the exercise 101st members used the toolkit to communicate with dismounted Soldiers to augment command and control during the simulated assaults.

In August, 101st Soldiers used advanced aerial tier and command and control technology, providing commanders with more communication with 80 aircraft flying from Fort Campbell to Fort Johnson, Louisiana.

‘War is changing’

The leader of Army Futures Command, Gen. James Rainey published the first of a series of articles in Military Review, beginning in August detailing the “transforming in contact” initiative and how the Army faces the most change in traditional warfare since World War II.

Rainey said technology evolves at a rapid pace and said the Army needs to quickly evolve technologies before they become obsolete. The commander added that the Army must change and evolve with the technology through doctrine, training and policy.

He said that the Army should document requirements for specific battlefield capabilities rather than individual pieces of technology and work with Congress on the Army’s fiscal flexibility.

Rainey said the Army needs to acquire useful technology, such as artificial intelligence, quicker instead of waiting for future capabilities to develop.

He encouraged putting the latest warfighting technologies into Army formations to encourage needed transformations, including the implementation of next generation combat vehicles, robotics and the latest command and control equipment.

He cited human-machine integration as a capability that reduces risk to Soldier safety and allows Soldiers to focus on decision-making tasks that require humans.

Project Convergence expands its scope

The Army’s annual series of modernization experiments, Project Convergence continued to evolve in 2024, expanding its scope and scale.

From Feb. 23 to March 20, more than 4,000 participants including members of partner nations from Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand took part in Project Convergence Capstone 4 in the western United States. The Air Force, Marines and Navy also contributed PC-C4, which experimented with more than 200 technologies.

PC-C4 successfully saw the Army, partner nations and other military branches successfully integrate sensors and fires without wasting unnecessary munitions.

The Army hosts Project Convergence annually to inform the integration of new technologies and capabilities to gauge the effectiveness of weapons and defense systems.

Project Convergence expands to Europe and the Pacific

To gain a better understanding of the needs of geographic combatant commands, the service executed more series of experiments in Project Convergence Europe and Project Convergence Pacific in 2024. The Army performed the tests in the context of near-peer regional adversaries, noting the geographic and regional obstacles.

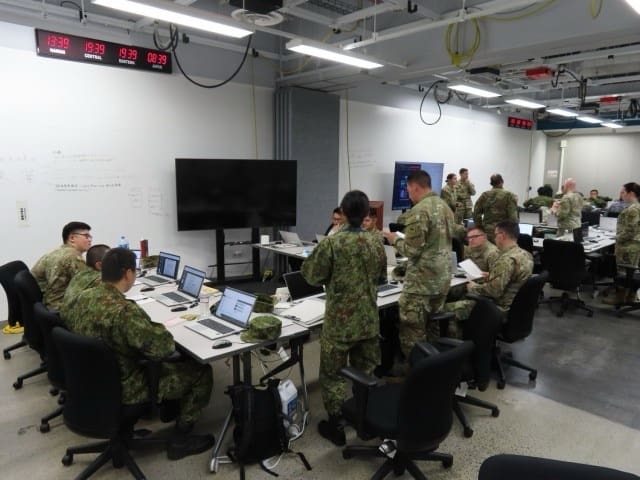

PC Europe focused on the Joint Warfighting Assessment as part of the Avenger Triad Exercise from Sept. 10-19. During the computer-assisted, command post exercise the Army focused on improving force readiness, acquiring Soldier feedback on modernization solutions, integrating and evaluating multi-domain operations concepts and assessing joint and multi-national interoperability.

In June, PC Pacific joined the multi-national exercise Valiant Shield 24 at locations in South Korea, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Japan and Washington State. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command led the field training exercise with troops from the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Space Force, Coast Guard and partner nations.

Army Futures Command, headquartered at Austin Texas conducts 60-70 experiments annually, including Project Convergence Europe and Project Convergence Pacific with new technologies to augment readiness and the capabilities of Army formations.

By Joe Lacdan, Army News Service