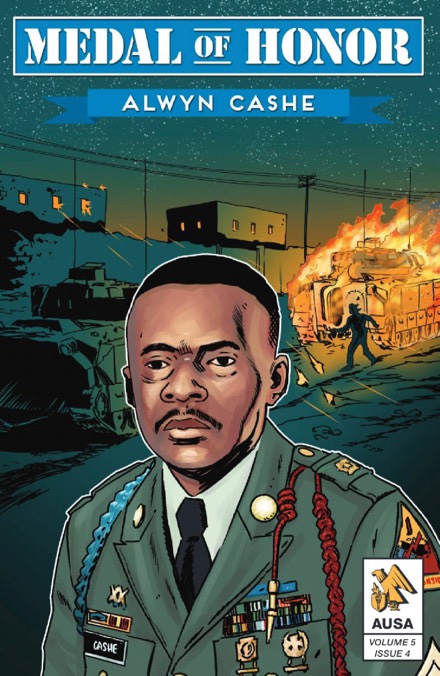

Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe, who ignored his own wounds and repeatedly entered a burning vehicle to save his soldiers, is the focus of the latest graphic novel in the Association of the U.S. Army’s series on recipients of the nation’s highest award for valor.

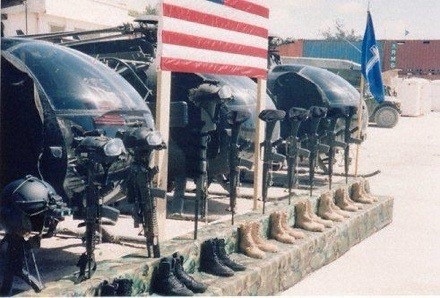

Medal of Honor: Alwyn Cashe tells of the infantryman’s actions on Oct. 17, 2005, when his Bradley Fighting Vehicle was struck by a roadside bomb near Samarra, Iraq. Cashe suffered terrible burns, but he kept returning to the burning vehicle to rescue his soldiers.

Cashe pulled six soldiers and an Iraqi interpreter from the wreckage and made sure everyone was taken care of before agreeing to be evacuated. Suffering burns on more than 70% of his body, Cashe died three weeks later.

“I’ve been wanting to tell this story for years. Alwyn Cashe’s actions were extraordinarily heroic, and I am glad he received the recognition he is due,” said Joseph Craig, director of AUSA’s Book Program. “I’m also glad we had such a talented team to put this book together.”

Medal of Honor: Alwyn Cashe is available here.

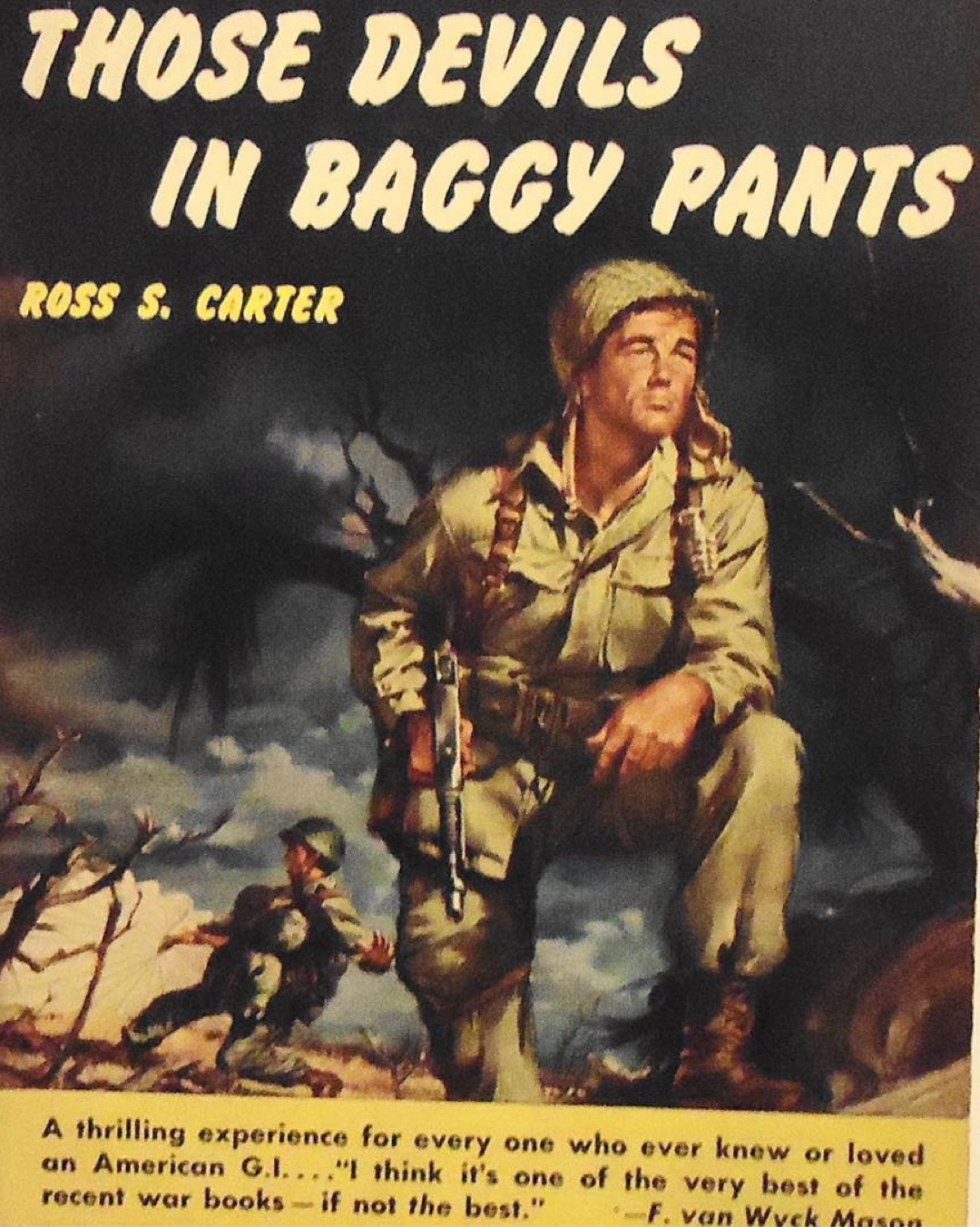

AUSA launched its Medal of Honor graphic novel series in October 2018. This is the 20th novel in the series. A paperback collection of the four issues produced this year is scheduled for release in the fall.

The digital graphic novels are available here.

A native of Oviedo, Florida, Cashe joined the Army in 1989. He served in South Korea, Germany and at installations across the U.S. and deployed in support of the Gulf War in 1991 before becoming a drill sergeant at Fort Benning, now known as Fort Moore, Georgia.

He participated in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and deployed there again in 2005 as a platoon sergeant in the 3rd Infantry Division’s 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment.

On Oct. 17, 2005, Cashe and his soldiers were on a nighttime patrol near Samarra when his Bradley Fighting Vehicle came under enemy fire and was hit by a roadside bomb. The blast tore into the vehicle’s fuel cell, causing it to burst into flames.

Drenched in fuel, Cashe escaped through a front hatch. His uniform began to burn as he and another soldier pulled the Bradley’s driver to safety. Already suffering from severe burns, Cashe refused to stop, moving back to the Bradley’s troop compartment to help his soldiers trapped inside, according to his Medal of Honor citation.

Ignoring the pain and the incoming enemy fire, Cashe opened the troop door and helped four of his soldiers to safety. When he noticed that two other soldiers had not been accounted for, he went back to the burning Bradley to get them.

“Despite the severe second- and third-degree burns covering the majority of his body, Cashe persevered through the pain to encourage his fellow soldiers and ensured they received needed medical care,” the citation says.

Cashe died Nov. 8, 2005, at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. He was 35.

While he was quickly awarded the Silver Star, the nation’s third-highest award for valor, there was a long campaign to have his award upgraded after the extent of his actions became known.

On Dec. 16, 2021, Cashe posthumously was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Each AUSA graphic novel is created by a team of professional comic book veterans. The script for the graphic novel on Cashe was written by Chuck Dixon, whose previous work includes Batman, The Punisher and The ‘Nam.

Pencils and inks were by PJ Holden, a veteran of Judge Dredd, Battlefields and World of Tanks; colors were by Peter Pantazis, who previously worked on Justice League, Superman and Black Panther; and the lettering was by Troy Peteri, who has worked on Spider-Man, Iron Man and X-Men.