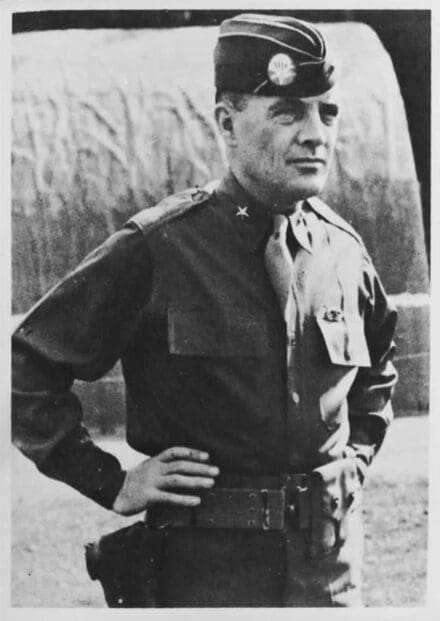

Bobby Ray Inman is a retired Navy Admiral. An Officer Candidate School graduate and the first Naval Intelligence Officer to earn four stars as a Flag Officer. During the 1970s and into the early 80s, ADM Inman served as Director of Naval Intelligence, Vice Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, Director of the National Security Agency and Deputy Director of Central Intelligence. Interestingly, he held these last two posts simultaneously for a period, pushing the two agencies to work more closely. He did this by sending memos back and forth to himself, approving them as he went along.

In response to the Beirut bombings of the US Embassy and Marine Barracks, ADM Inman chaired a commission on improving security at U.S. foreign installations.

Some SSD readers may know him for sitting in the Board of Directors of Academi, a corporation formerly known as Blackwater.

His list of rules are well known within the Intelligence Community and may seem at first glance only suited for senior officers working in Washington. While some are specific to that unique arena, many should be implemented immediately upon starting a career and consistently throughout.

1. Conservation of enemies.

2. When you are explaining you are losing.

3. Something too good to believe probably is just that, untrue.

4. Go to the Hill alone.

5. Wisdom in Washington is having much to say and knowing when not to say it.

6. Never sign for anything.

7. The only one looking out for you is you.

8. If you think your enemy is stupid, think again.

9. Never try to fool yourself.

10. Never go into a meeting without knowing what the outcome is going to be.

11. Don’t change what got you to where you are just to get to the next place.

12. Intelligence is knowing what the enemy doesn’t want you to know.

13. Nothing changes faster than yesterday’s vision of the future.

14. Intelligence users are looking for what is going to happen, not what has already occurred.

15. It is much harder to convince someone they are wrong than it is to convince them they are right.

16. For Intelligence Officers in particular there is no substitute for the truth.

17. By the time intelligence gets back to a user with the answer the question usually has changed.

18. Always know your blind spots, get help to cover them.

19. The first report is usually wrong, act but understand more is to come and it will be different.

20. You can never know too much about the enemy.

21. Tell what you know, tell what you don’t know, tell what it means.

22. Tell them what you are going to say, tell them, then tell them what you told them, they might remember something.

23. Never have more than three points.

24. Never follow lunch or an animal act.

25. Believe is correct, intelligence officers never feel.

26. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

27. Boredom is the enemy, not the time to any briefing.

28. If you can’t summarize it on one page, your can’t sell it to anyone.

29. Always allow time to consider what the enemy wants me to think, is he succeeding or am I?

30. If you can’t add value, get out of the way.