The SCUBAPRO Seawing Nova turns ten years old. The Seawing Nova appeared in 2009 and

immediately turned heads with its clean sheet streamlined design. The original Seawing fin inspired it with its radical blade profile.

This innovative fin caught the attention of designers and engineers worldwide. It won Popular Science magazine’s “Best of What’s New in 2009” award. Then it won the ScubaLab Testers Choice award for the best performing new fin of 2010. In 2011 the Seawing Nova won the prestigious, internationally- recognized Red Dot Award for product design, then in 2013, when a full-foot version came out, it won the Testers Choice for the best full-foot fin of the year. And in 2015, after benefitting from several upgrades to make a great fin even greater, the improved Seawing Nova won the Testers Choice award for the best fin of the year once again.

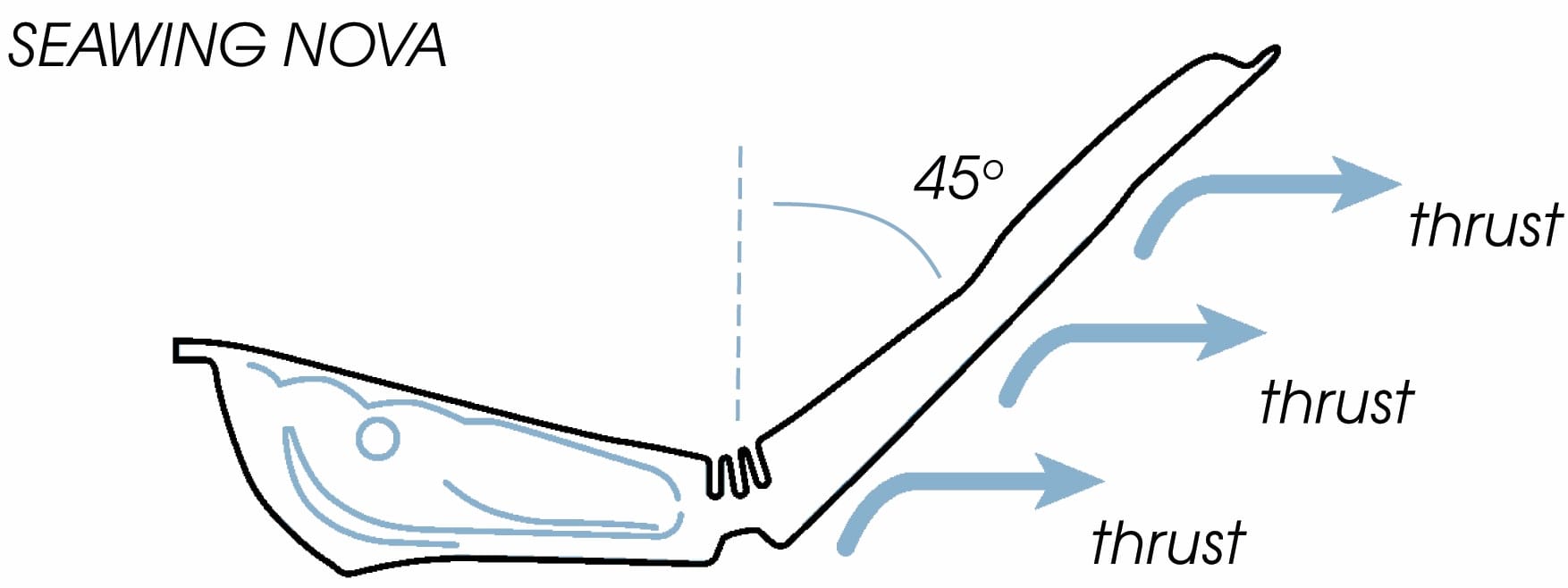

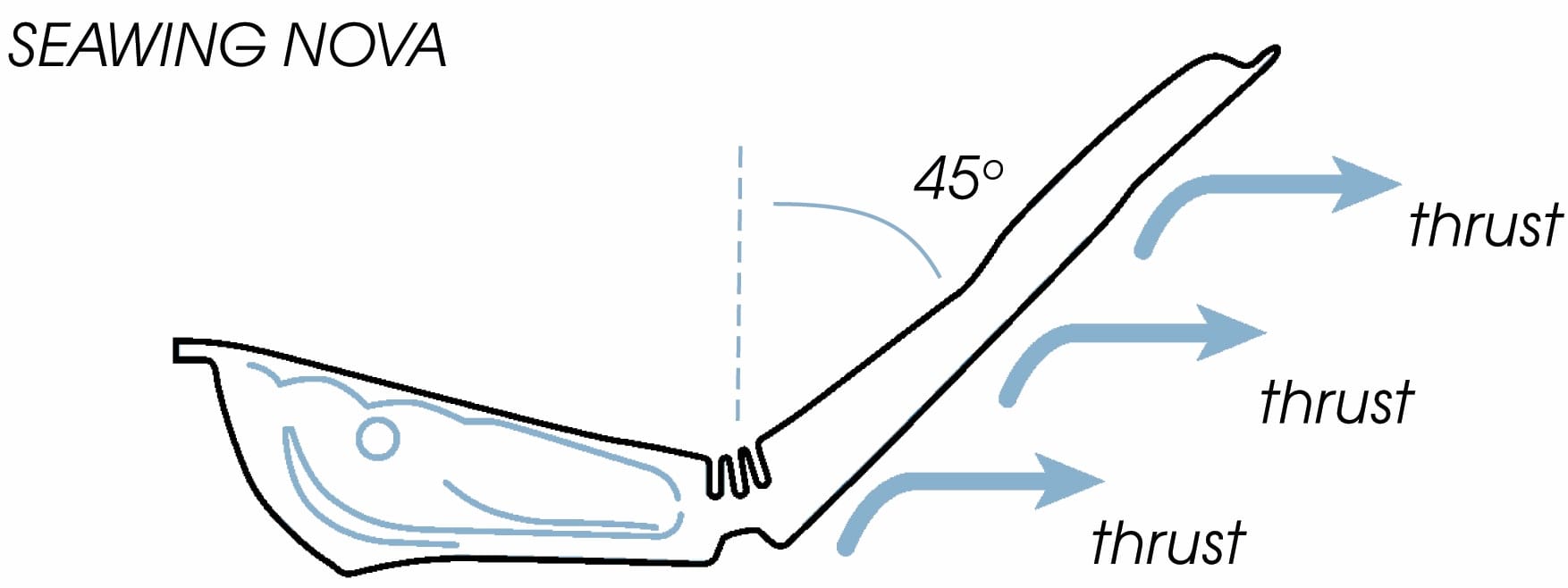

Built with a space-age Monprene elastomer that is virtually indestructible. (The Seawing Gorilla includes a special additive to enhance stiffness and increase feedback.) Spotlighting its proprietary G4 (4th Generation) articulated hinge with enlarged Pivot Control notches that enables the entire wing-shaped blade to pivot and generate thrust, the Seawing Nova produces a propulsive snap that can rocket you through open water at top speed or propel you along reefs or in and out of tight spots with total control—all with little to no ankle or leg strain. Pivot Control technology ensures that the most efficient 45-degree angle of attack is maintained no matter how easy, or hard you kick.

The Seawing Nova also excels in low-speed maneuvering, including frog kicks, reverse kicks, and turtle backing. Offers improved handling when making small directional adjustments. This is due in large part to a slight increase in rigidity across the trailing edge of the blade, which has ratcheted up responsiveness and thrust at full power while requiring no increased kicking effort in cruising mode.

The fin features a well-engineered footplate that extends all the way to the back of the heel, maximizing power transmission while minimizing stress on legs and ankles. Co-molded Grip Pads provide efficient non-skid footing on wet surfaces. The famous bungee straps have been redesigned and updated, reducing overall weight and providing enhanced durability.

• Monprene Shroud is 35% lighter.

• Re-engineered with the injection gate relocated to provide enhanced durability.

• More flex means improved comfort.

• It’s the same bulletproof 8mm marine-grade bungee as in existing Seawing Nova Straps.

The fin also features the popular self-adjusting heel strap made of marine-grade bungee. This bungee is highly elastic, resistant to the elements, and the soft heel pad with an over-sized finger loop is comfortable and simplifies doffing and donning. It can also be fitted with a steel spring strap that also fits on the twin jet fins

SEAWING NOVA FAMILY OF FINS

• Seawing Nova Open Heel This high-performance fin delivers the power, acceleration, and maneuverability of a blade fin, with the kicking comfort and efficiency of a split fin. Available in five sizes (XS-XL).

• Seawing Gorilla Open Heel

While identical in design to the Seawing Nova, the Seawing Gorilla uses a special additive in its compound to provide more stiffness and snap to the blade. This results in more power, speed, and control for divers who like a stiffer fin with more feedback in their kicks. The more rigid blade also allows for more effective sculling, frog-kicking, and reverse-kicking, making it an excellent choice for tech divers. Available in five sizes (XS-XL) Graphite (while supplies last) Black is available by special order.

THE SEAWING NOVA ADVANTAGE

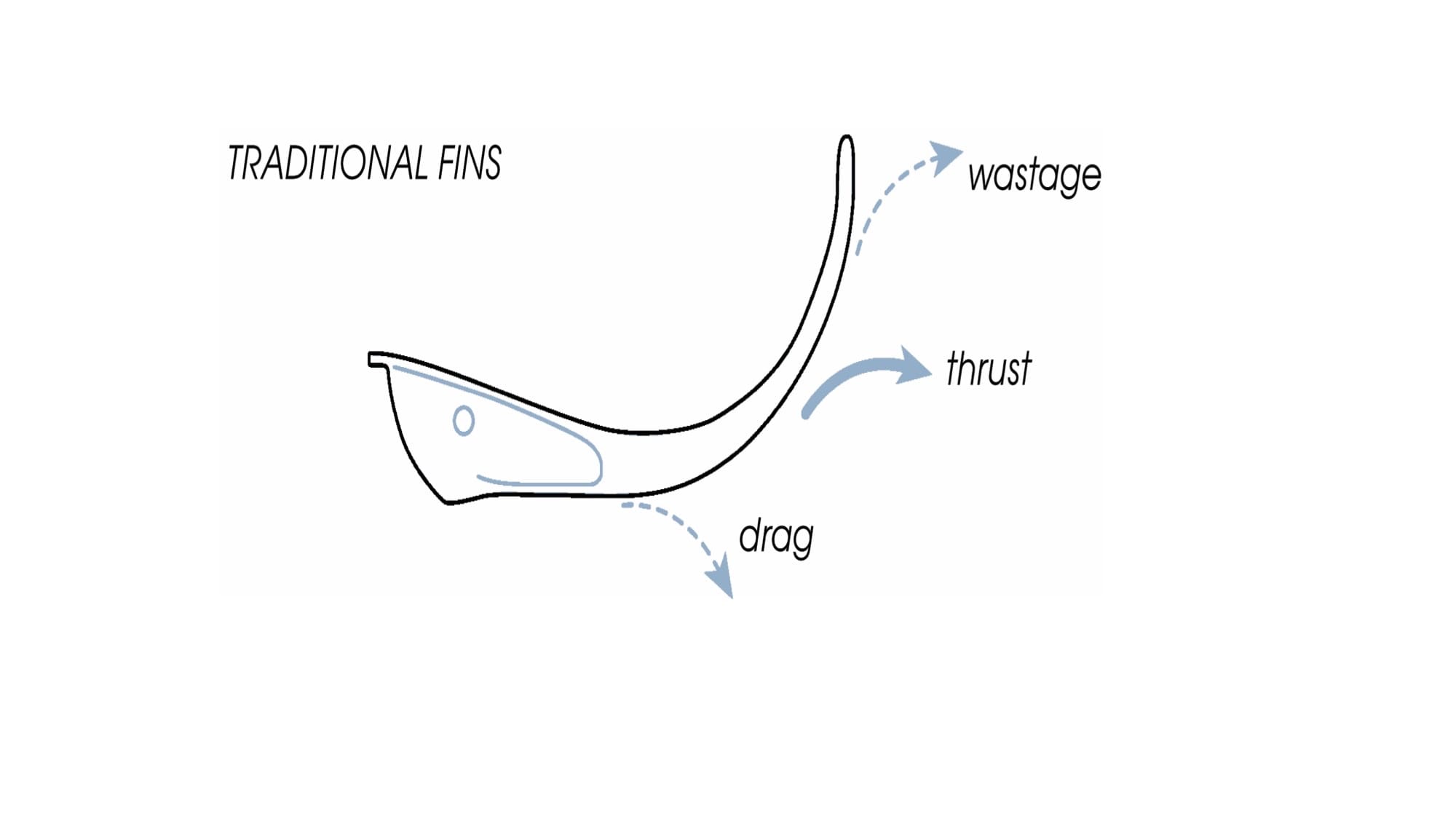

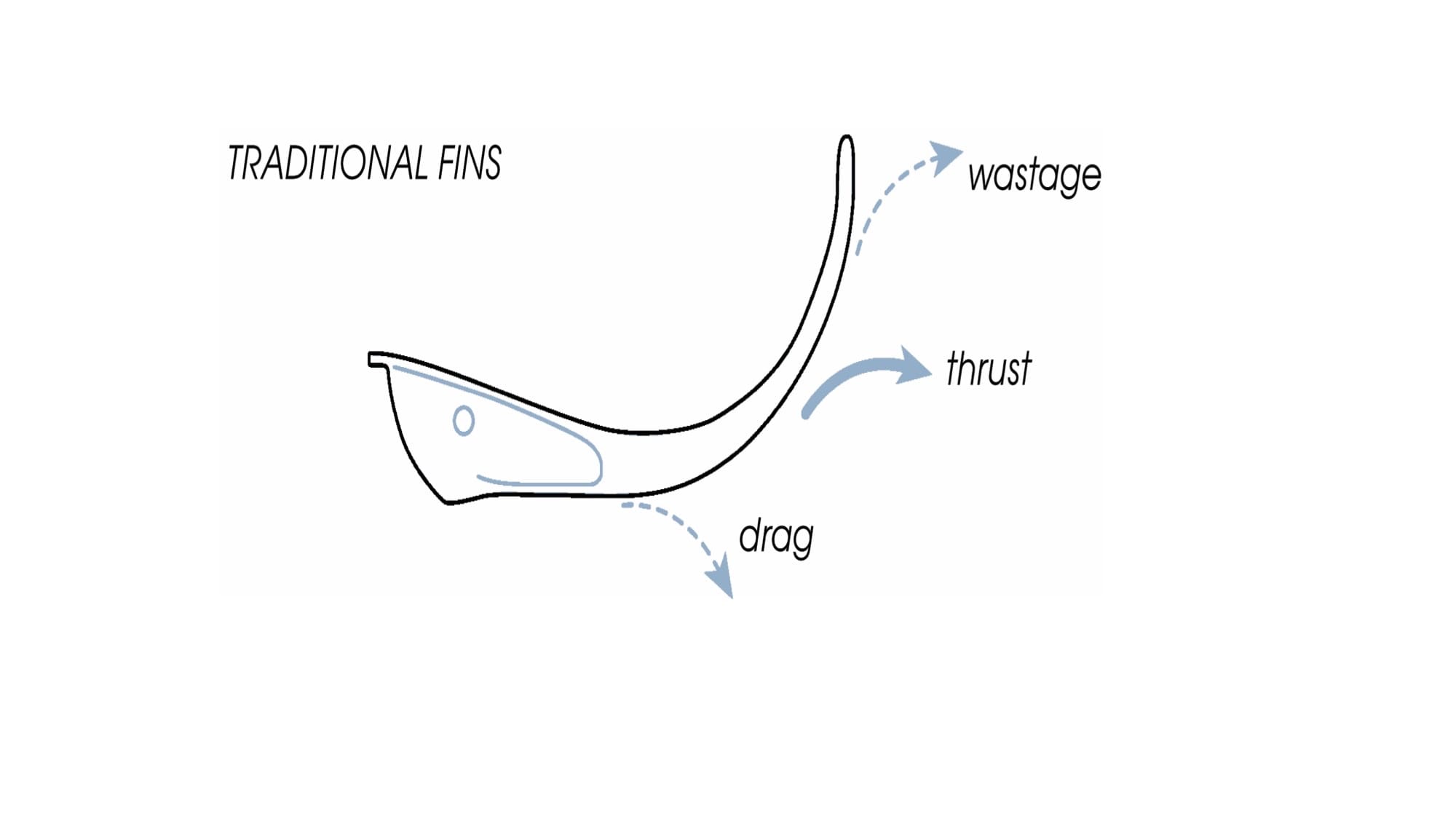

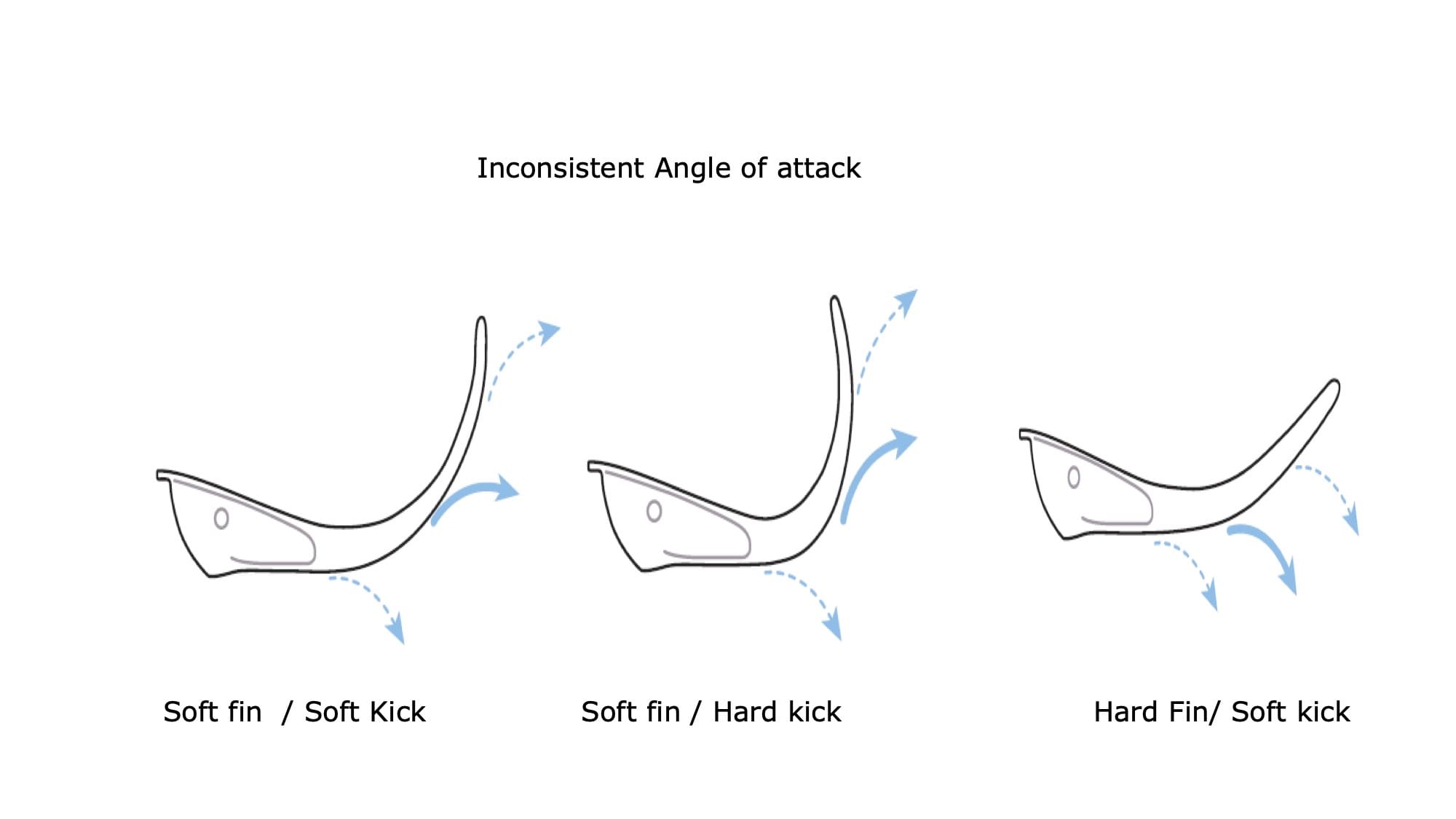

On a traditional paddle fin, during a typical kick stroke, as water flow hits the fin, the blade will curve along its length. This means that the blade’s angle of attack, relative to the water flow, is going to be different at different points on the blade. In such a case, the leading edge remains too flat to generate efficient thrust, while the trailing edge flexes too much. Consequently, only the midsection can produce dynamic thrust.

The Downfalls of traditional fins

The Seawing Nova will always maintain the most efficient angle of attack along the entire length of its blade because instead of the gradual curve of a traditional blade, the Seawing Nova’s blade stays relatively flat due to the G4 articulated joint that allows the entire blade to pivot (like the tail joint of a whale or dolphin). Also, the blade is longitudinally reinforced by pronounced rails that help prevent curvature (this is supported by the monocoque effect that takes place when the Variable Blade Geometry wing tips arc upwards).

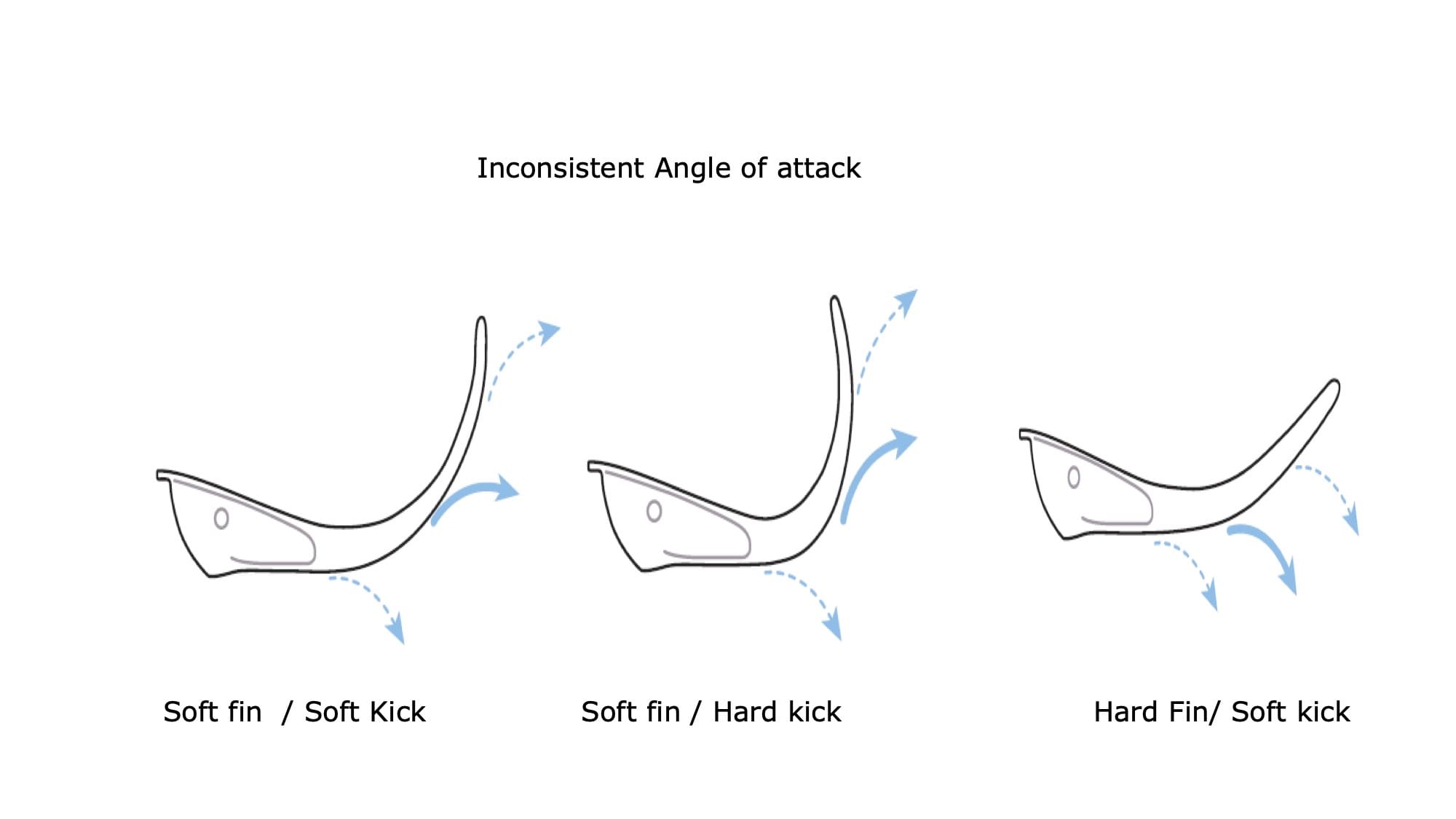

On a traditional paddle fin, the harder you kick, the more the blade bends. That means a soft fin will achieve the ideal 45-degree angle when it’s kicked gently but will over-bend and lose thrust when it’s kicked hard. Stiffer fins, on the other hand, achieve that ideal 45-degree angle when kicked hard but remain too flat to be efficient when kicked gently. Consequently, both types require the diver to compromise his or her kicking style to get any efficiency out of the fin.

On the Seawing Nova, by creating a fixed angle of attack, the unique G4 hinge also allows the blade to flex easily to that ideal 45-degree angle but prevents it from flexing further as kicking strength increases. Therefore, the angle of attack is close to the optimal 45 degrees at all times, regardless of kicking strength. Kicking easy or kicking hard, the Seawing Nova lets you always maintain the optimum angle of attack for maximum performance.

On a traditional paddle fin, that non-productive or “dead” section where foot pocket and blade meet creates a lot of drag without generating any thrust.

On the Seawing Nova, engineers eliminated this section, creating a “Clean Water Blade” where water flows cleanly onto the working part of the blade, reducing drag and increasing thrust.

The ‘dead’ section between the foot pocket and the blade of a traditional fin generates drag but not thrust. We removed it! This means that water is free to flow cleanly onto the working section of the blade. Drag is reduced, and thrust is increased.

MATBOCK Skins, SCUBAPRO, has been working with MATBOCK to develop Skins for SCUBAPRO fins that will help you adapt your fins to every environment. Perfect for Over the Beach or River and Stream crossing. The patent Pending MATBOCK Skins is a multi-layer adhesive/ fabric laminate designed to give the user the ability to camouflage any surface desired. The Skins are waterproof, and oil resistant can be reused mutable times. Skins are designed and laser-cut specifically for the following fins, Seawing Nova’s, Gorilla, and SCUBAPRO Jet fins.