Several years ago one of my children asked at dinner, “Dad, what’s a leg?” I replied, “that’s your mother’s side of the family, son.”

Several years ago one of my children asked at dinner, “Dad, what’s a leg?” I replied, “that’s your mother’s side of the family, son.”

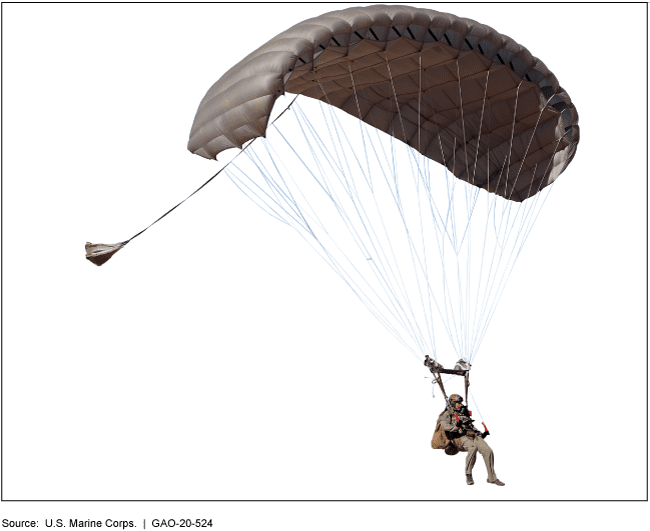

The House Armed Services Committee directed the Government Accounting Office to review the Army and Marine Corps’ procurement of free fall parachutes.

Their report examines the acquisition strategies used by the Army and Marine Corps for their parachute programs and the extent to which the Army and Marine Corps programs are meeting their cost, schedule, and performance goals.

The Army awarded its contract for the Advanced Ram Air Parachute System—known as the RA-1—in 2011. The Marine Corps awarded its contract for the Enhanced-Multi Mission Parachute System—now called the PS-2—in 2018.

GAO found that both programs are on cost and schedule.

Download your copy here.

The MultiCam Vic Project is a collaboration between Firebird Skydiving and Airwalk to offer a run of MultiCam and MultiCam Black hightops.

Expect some slight changes before production.

Participate in the survey if you are interested.

FORT PICKETT, Va. – The sky above this installation was once again filled with paratroopers dropping from aircraft as the Quartermaster School resumed airborne operations April 22.

The Virginia National Guard base – a 45-minute drive west of Fort Lee – is where the QMS Aerial Delivery and Field Services Department conducts airborne operations for parachute riggers.

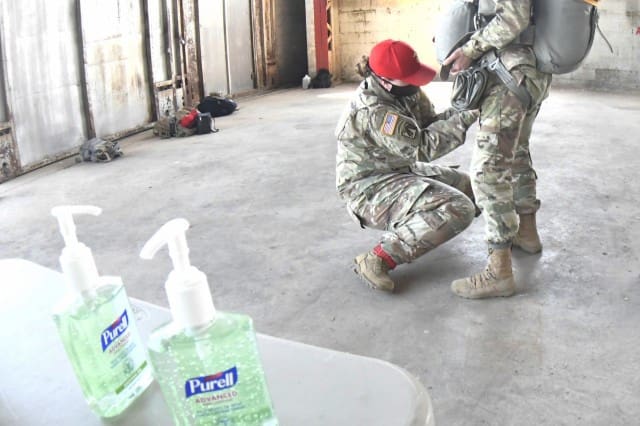

Staff Sgt. Raymond Debusshere, an instructor, said his department last conducted jump training March 12. It has since undergone a thorough review and reassessment to determine how to best conduct such operations without putting paratroopers at risk for contracting COVID-19.

“We’ve added various safety precautions,” said the jumpmaster from a hangar skirting Pickett’s massive airfield. “We are practicing spacing, and every jumper out here has a face mask. In addition, we’re using hand sanitizer before and after every JMPI. We also added lifts (flights) to maintain spacing on the aircraft.”

JMPI, or Jumpmaster Personnel Inspections, is a safety process ensuring every paratrooper is prepared for the operation prior to boarding the aircraft. Jumpmasters meticulously check straps and equipment placement to ensure they’re secure and not likely to cause injury. With all the precautions taken, the operation took longer than usual, Debusshere admitted. “(It) added a lot to the process, but it was crucial and it worked out well.”

The QM School is one of the few Army entities outside of operational units that has resumed airborne operations. Not surprisingly, the task of securing aircraft through normal channels for the mission proved to be a challenge because the coronavirus pandemic has shifted air support functions across the Department of Defense.

“It was an undertaking calling different units and trying to get them to come in,” said ADFSD’s Kenneth Pygatt, airborne operations coordinator. “Some units have been willing, but their commands (are being highly selective in the approval of flights). It has been a task to bring it all together, but we got it done.”

There are no aircraft assets assigned to Fort Lee, thus, airborne operations must be coordinated through aviation units spanning the entire region. Active duty Marine aviators from Cherry Point, N.C., supported the April 22 drop. There are roughly 20 different aviation units that support the rigger course, Pygatt said.

Despite all that has taken place to resume training, parachute rigger students seemed oblivious to the changes. Many of them were in the first few weeks of the 92-Romeo course when the pandemic-necessitated measures such as social distancing became the “new normal.” It was apparent at the airfield they had become accustomed to it. They were focused on the day’s mission – jumping a parachute they packed themselves to demonstrate confidence in their abilities. It has always been a course graduation requirement. All of that seemed to overshadow even the pandemic precautions.

“I’m just excited to jump,” said a masked Pvt. Angelica Gonzalez while waiting for her lift. “It has been a while since I’ve been up there (all students complete the Basic Airborne Course at Fort Benning, Ga., before coming to Fort Lee), so it’s a refreshing moment for me.”

The Charlie Company, 262nd QM Battalion Soldier was one of 28 rigger students making their culmination jump. Numerous NCOs and officers also participated to keep their airborne-qualification status current.

More than 600 Parachute Rigger Course students graduate from ADFSD annually. The Fort Lee training is 14 weeks long.

By Terrance Bell

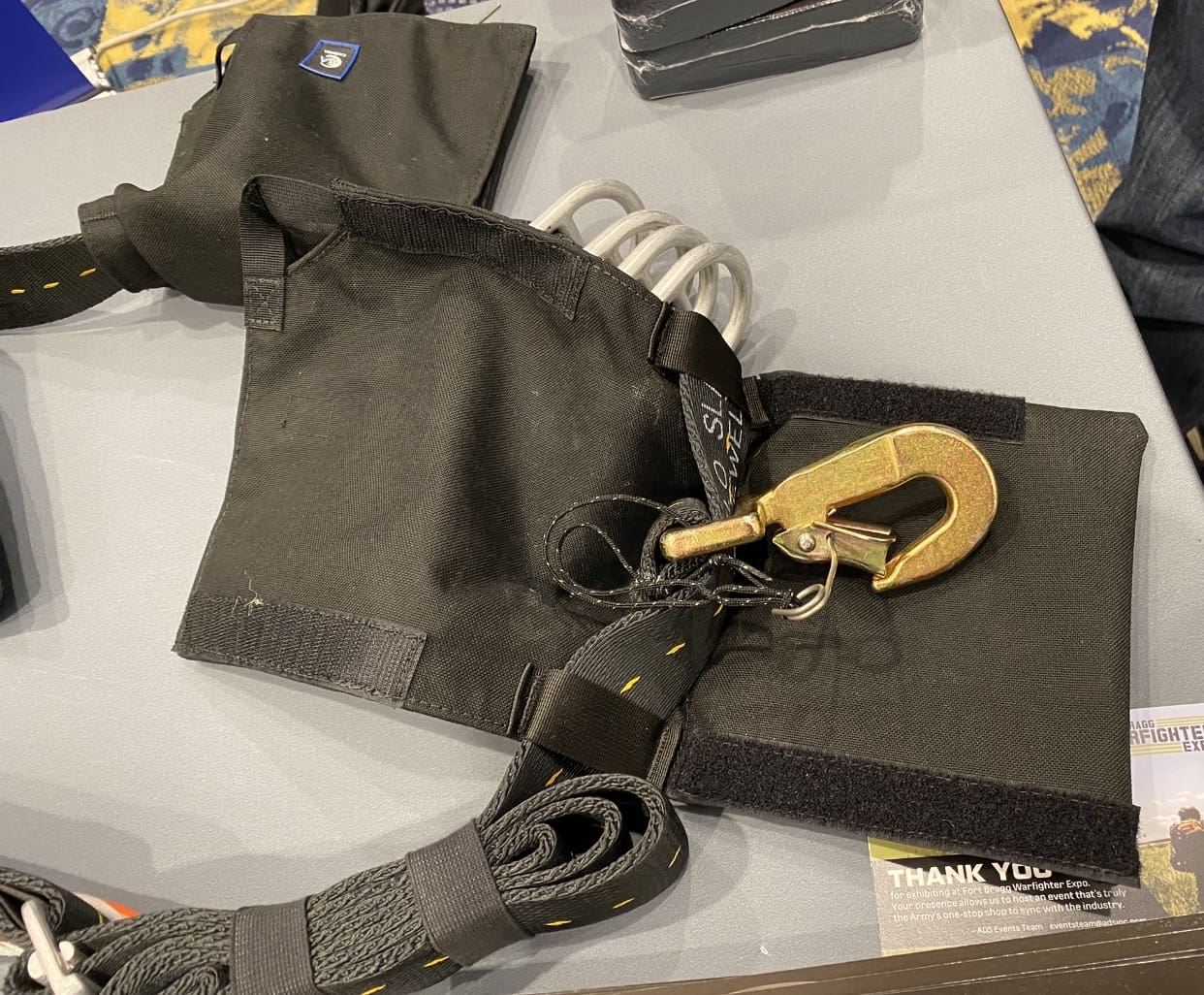

My vote for the best product at the Expo was the Helo Static Line Anchor System from Capewell Aerial Systems.

No more making your own. This system is preconfigured, complete with padding and will sustain more than the required 5200 lbs dynamic load (two jumpers simultaneously falling 14 feet). In fact, they tested the system all the way up to 12,000 lbs.

It also comes with a kit bag for storage which can also be used for recovered d-bag storage while in flight

CAMP LEMONNIER, Djibouti (AFNS) — The Air Force uses more than 20 types of parachutes to conduct personnel recovery, airdrops and asset insertion into combat zones. Knowing what type of parachute is required for each mission and verifying the safety of those parachutes is the job of a parachute rigger.

This responsibility on Camp Lemonnier is up to the 82nd Expeditionary Rescue Squadron Aircrew Flight Equipment riggers, deployed from Moffett Federal Airfield, California.

“Being a rigger, everything we do has to be 100 percent,” said Tech. Sgt. Isaac Corniel, the 82nd ERQS AFE NCO in charge. “There is no room for mistakes. There’s no room for error. Their lives are in our hands. Even if we have a small twist in a line we want to make it straight, as it can mean someone’s life.”

Being deployed to Djibouti has allowed the 82nd ERQS AFE to train on real-world missions unlike any other training they can get at home station.

AFE riggers are required to pack a variety of chutes in a variety of conditions throughout the world to meet mission needs. The packing can take from 35 minutes to several hours to inspect and repack. Along with the complex quality control measures that must be performed.

“We just try to be the best that we can. We preach quality, quantity and efficiency,” Corniel said. “We are combined with a variety of military forces being deployed, so our guys get to train on more scenarios than they would at home.”

According to Corniel, being deployed to Africa has allowed the team to have hands-on experience with more airdrop missions, whereas back home they would only provide chutes for one or two drops a month. The AFE Airmen said they have grown their understanding on the job to make their deployment a success.

“The guys have been great. They all live up to the riggers creed; they know now what it is to be a rigger,” Corniel said. “We are a part of something special and we strive to keep the history of excellence between the pararescue teams and riggers.”

By SSgt Carlin Leslie , Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa Public Affairs

It has been awhile since I have done an article on tactical gear. In the last few days, I managed to get my hands on the new issue version of the Molle 4000 “Airborne” Rucksack. I do not own a lab coat so I am not in the position to objectively and scientifically test this ruck; but I can provide my initial professional evaluation. The opinions I am offering are influenced by my specific experiences and individual preferences; but I think I can provide some broadly applicable and valid observations and hopefully useful practical information for the reader.

Up front, I will make these points to frame my comments and for the reader to keep in mind. There is no such thing as perfect gear. I have never been issued or bought any load-bearing item that I was completely satisfied with out of the wrapper – ever. I believe that everything can be improved and even the best and most expensive gear still needs at least some “customization” to be optimized for each individual user. Indeed, I have already done some of that to this sample and will point out a couple of my modifications and my rationale as we go alone.

I did spend most of my military career on Airborne status as a jumper and Jumpmaster; so I have a great deal of hands-on experience with Airborne operations and techniques. I am also incorporating a number of pictures for illustrative purposes, and a couple of earlier SSD articles with other pictures are here and here for additional reference. As pointed out in the previous pieces, this ruck is being issued to the 82nd Airborne Division and other Airborne units in the Army. I expect that will eventually include the Ranger Regiment, SF Groups, and other ARSOF units because of the Army’s Title 10 responsibilities. There is also some indication that the Army is exploring expanding the issue of this ruck to at least some non-Airborne units.

Let us start with a size comparison. From left to right, and largest to smallest, are the Molle Large, the Molle 4000, the ALICE Large, and the Army’s Medium Rucksack. The Medium Rucksack has ~3000 cubic inches of space. I have a couple of extra pouches mounted as well as a beavertail so this one is probably in the ~3500 cubic inch range. The ALICE is approximately ~3800 cubic inches including the exterior pockets. The Molle Large bag is ~4000 alone and ~5000 cubic inches with a pair of Sustainment Pouches added as shown. As the name implies, the Molle 4000 is ~4000 cubic inches including the external pockets. Compared to the Molle Large, the Molle 4000 has considerably less available real estate for additional pouches. Still, although it may not look like it, it is possible to mount the issue Army or USMC Sustainment Pouches in a somewhat compressed fashion on either side as shown on the right of the ruck.

As the picture also shows, the 3 bottom exterior pockets on the Molle 4000 are approximately the same volume as those on the Large ALICE. Although, since the cordura material is stiffer than packcloth, I found that I could stuff just a little more into the ALICE pouches. The two on either side have a pass thru channel behind them like their ALICE counterparts. However, the opening is just barely big enough for a GI Machete Sheath to be slipped in – nothing any wider or fatter. The horizontal strap shown comes with the ruck and is labeled “Molle 4000 Compression Strap.” Back in the day, we used a GP Strap to do the same thing on the ALICE as shown. It serves to cinch the pouches and attached items like E-Tools to the ruck to minimize flop or bounce – much like the Brits use bungee cord around their old-school belt kits. No doubt, an old ALICE hand like me added this throwback item. I think today’s soldiers will find that it is a useful accessory.

The three smaller pockets towards the top of the rucksack look to be identical to the same pouches on the Large ALICE. They are indeed just as wide but are actually about an inch shorter. On the ALICE, those were very popular for everything from toilet paper, 550 cord, bungies for shelters, to dip cans and smokes. I have been told that they were originally sized to hold a 30 round M16 magazine. A magazine will indeed fit in the pocket; however, I never saw anyone use it for that purpose. I am not sure I believe the story anyway because the Large ALICE was type classified several years before the 30 round magazines became standard issue. Because they are not as deep, an M4 magazine will not fit in the small pockets on the Molle 4000. Still, I think the small pockets will be well received and provide troopers the option to segregate small items for quick access.

In its Airborne role, the Molle 4000 is actually only one-half of the equation – truly even less than half. IMHO, the true star of the show is a much improved Harness, Single Point Release, Molle (HSPR-M) that is being issued concurrently as a separate component. Note: NO portion of the new HSPR-M or any other air item is permanently sewn into the rucksack. Indeed, while rigging and de-rigging of the ruck is much faster with this new harness, the process would be very familiar for any American trained as a static line jumper in the last 30 years. That is a big plus; this new harness will be an easy transition for all jumpers and will actually be considerably easier and faster to check during Jumpmaster Personnel Inspections (JMPI). The new harness is also reverse compatible and can be readily used to rig any rucksack or jumpable load that could be rigged with the older HSPR.

In a nut shell, the big difference between the old and the new is that the release mechanism and attaching straps have been moved to the center of the HSPR-M rather than being positioned at one end near the friction adapters (metal buckles), as it was with the earlier version. Now, when rigged, the release mechanism remains centered on the bottom of the ruck while the friction adapters are routed all the way to the top. Throughout the Airborne operation, the jumper has full access to all the exterior pockets and can even access the main rucksack compartment rapidly if needed without completely derigging and rerigging. That feature alone is an especially important and welcome enhancement. That is because, in real-world contingency operations, mission critical items including ammunition and rations are routinely delivered to the jumpers at the airfield and right up to the point of boarding the aircraft. In short, the new HSPR-M represents a significant product improvement.

As far as I can tell, there is no intention to change the current Hook and Pile Tape (HPT) Lowering Line. Hook and Pile Tape = Velcro. As is Army SOP, I expect that current HPT Lowering Lines in OD (as shown) or Foliage will continue to be used as long as they are serviceable. Eventually, new lowering lines will be produced in Tan 499 as replacement items as required. The ALICE was issued with an instruction pamphlet and the Molle System has a manual; however, if there is a pamphlet for the issue Molle 4000, I have not seen it yet. I presume it will be an addendum to the Molle System and other applicable combat equipment rigging manuals shortly.

Consequently, since I have not seen the instructions, some of my observations – especially about rigging procedures – are just educated guesses. However, while I might not have rigged it precisely in accordance with the official SOP, I bet I am real close. I can guarantee that I have rigged this ruck in a way that is safe to jump and will work as intended. However, this is not a rigging class and I will let the pictures speak for themselves for the most part. As I said, those of you with experience with the old HSPR will find it mostly familiar.

In some of the pictures, the reader may notice that I replaced all the elastic loops and two sided Velcro that comes with the Molle 4000 for strap management. Instead, I prefer to use ITW triglides. The triglides provide an additional tensioning device and failsafe to keep straps from slipping or coming inconveniently unstowed from an elastic retainer. If you read my three-part article on the ALICE, you also know that I am no fan of wrap around waist belts / pads. Therefore, I also traded out the pad that came with the Molle 4000 for a DEI pad designed for the 1606 frame. It hugs the full curvature around the bottom of the frame. I find that spreads the felt weight across the entire area of the body in contact with the pad. Because of the curve, the pad “cups” the back and sides rather than putting pressure on any one spot.

In combat, soldiers put a pack on and off countless times a day in sunlight and darkness and in blizzards and driving rain – and often under fire as well. It is tiring. Uncomplicated is better. Rucksack configurations that are not prone to getting tangled up with other gear or require a lot of fiddling steps to mount and dismount are eminently more practical and appreciated. From my perspective, the DEI style pad integrates much better, especially with the belt worn gear I personally favor, and provides about as much comfort as possible without the negatives. Warfighting ain’t backpacking; and if I am going into a fight this is how I prefer to run my ruck. Otherwise, as the reader can see, the Molle 4000 bag and suspension system is pretty basic. As previously reported, it is a hybrid, half ALICE and half Molle. For example, on the inside (not shown) is an ALICE style sewn in radio pouch and a Molle style zippered panel that can be used to divide the main compartment in half. I think soldiers will actually appreciate the pack’s utilitarian nature.

I am not about to throw shade on the people involved in the design, development, or testing of the Molle 4000. I appreciate their hard work and I am sure they delivered exactly what they were asked to deliver. However, I would be negligent if I did not point out the areas that I feel strongly need improvement. Specifically, there are four problems I see with the Molle 4000: one relatively minor, and three major. First, the minor issue. The current drain grommets on the exterior pouches and the bottom stow pocket are too small. They are much smaller than those on the ALICE or the Molle Large. I do not know why. More importantly, while there are small grommets at least on the bottom of the air items stow pocket, there are no drain grommets at all on the bottom of the rucksack itself. Therefore, if water gets into the main compartment of the ruck it will not drain. That should be an easy and quick fix.

The second problem is that the zipper providing access to the bottom of the rucksack’s “sleeping bag compartment” is too short. It does not even go half way around the ruck. That means the opening is narrow rather than a fuller size as found on the Molle Large or FILBE. In turn, that means soldiers will have a difficult time getting something the size of a patrol sleeping bag – let alone a full sleep system – through that unnecessarily restrictive opening. In contrast, the zipper on the air items stow pocket goes a full 2/3 of the way around. It is a good thing they added the bottom access zipper; the prototype Molle 4000 did not have one at all. No doubt, soldiers can live with it as is – if absolutely necessary – but they should not have to. Therefore, the bottom of the rucksack needs some modification or even redesign (see problem four) to make access much more user friendly then it is now.

The third – and more significant – problem is that the wide upper pad of the Molle 4000 entirely covers the horizontal recurved arms of the 1606 frame. I submit that those arms are its single best feature. Certainly, the center crossbar has to be padded because otherwise it would press uncomfortably against the soldier’s spine. However, as long as about 2 inches on each end are exposed beyond the padding, those arms provides essential “hard points” to tie down heavy and outsized items like mortar baseplates. It would be a shame to keep something like that completely covered up and unavailable when they could be of great utility to the soldier carrying a combat load. Note: the USMC FILBE rucksack also uses the 1606 frame. A friend pointed out to me recently that the FILBE prototypes had a wide pad similar to the Molle 4000, thus leaving the recurve arms unusable. However, the issue FILBE featured a changed pad system that left the ends of those arms exposed rather than covered. I presume that the USMC saw the greater tactical value in making that modification. I suggest the Army do likewise before the Molle 4000 goes into expanded production.

The fourth, last, and most glaring, problem with the Molle 4000 is the air item stow pocket arrangement itself. It is a superfluous design gimmick that is more trouble than it is worth. I know someone asked for it – and some people must like it. It is still demonstrably unnecessary. I would argue emphatically that paratroopers have no pressing requirement for a pocket on their rucksack dedicated solely to the storage of air items. The first clue should be the fact that we have gone DECADES without ever identifying the need for such a pocket before. In all my years of jumping, I do not ever recall a single time when stowing my air items – without a dedicated pocket – was a problem. I do not remember it being an issue for anyone else either.

Even more to the point, paratroopers have no TACTICAL need whatsoever to carry air items off the dropzone. Once those items have served their one and only purpose – to deliver a paratrooper and his combat load safely to the ground – they are all expendable. They always have been. The stuff is meant to be abandoned in order to unburden the trooper as he moves as rapidly as possible to his unit assembly area and / or combat objective. That includes the parachute, harness, kit bag, weapons cases, HSPR, lowering line, and any other packing material that dropped with us. The troopers shed it all, either immediately upon landing or at the first opportunity. It is dead weight.

Sure, we have a habit of bagging it all up and carrying everything to a convenient centralized location so that the Riggers can take the chutes and accessories back to repack and refurbish. That practice is a sensible conservation of our training resources and money. The fact is, we only issue select air items (HSPR & HTP Lowering Line) to individuals because it is convenient and a time saver for troopers to rig their rucks – and perhaps get their rucksacks pre-inspected by a unit Jumpmaster – before they get to the departure airfield to draw their parachutes, weapons cases, kit bags, etc. to finish the rigging process.

However, all of that represents an entirely ADMINISTRATIVE requirement we levy on ourselves that has nothing to do with jumping into combat. And after all, a successful combat jump is ultimately the only jump that really matters – tactically, operationally, and strategically – to the individual paratrooper, the Airborne unit, the Army, and finally the Nation. We do not need to teach our troopers bad habits or add an unneeded design feature to our load carrying gear to support a bad habit. Airborne leaders should constantly be making the clear distinction between what we do routinely on some CONUS dropzone in training vice what needs to happen on a hot DZ in some hostile place.

The air items stow pocket is certainly not necessary for the rigging process. In fact, the pocket actually slows down the procedure rather than making it smoother. It would be much cleaner if the bottom of the Molle 4000 just had four web bars sewn on that would index the HSPR’s release mechanism in both directions on the ruck. See my mockup using the blue painters tape (above). Then, the entire design of the bottom of the rucksack could be significantly simplified. The bottom of the rucksack itself would be just that – the bottom. The now redundant sleeping bag compartment zipper could be eliminated entirely. The 2/3s zipper would be retained and would give better access to the interior anyway. The ruck could be rigged even faster and there would no longer be a need to secure the flap of the open stow pocket anymore either. That would be markedly better.

Bottom line: the new HSPR-M is a home run for Natick and whoever designed it. The Molle 4000 Rucksack is a solid base hit but has some shortcomings that really need to be addressed. I think that perhaps some decision maker(s) got a little too fixated on securing air items rather than concentrating on optimizing the ruck itself for combat. Even in an Airborne unit, the Molle 4000 will just be a rucksack on a soldier’s back 95% of the time. It could be a much better ruck with some relatively modest adjustments. As is, I think soldiers will generally like it. If those things I have identified are fixed, I think they might even love it. Granted, no one asked me for my opinions, but there they are. De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

Recently, the 82nd Airborne Division’s Devil Brigade conducted an Airborne Operation. While many Devils were in flight to the drop zone, members of the Brigade Staff were testing the CASPAN (Command and Staff Palletized Airborne Node) – a large, roll-on/roll-off workstation designed for in-flight mission command collaboration with the Key-Leader Enabler Node, allowing Devil 6 to maintain communication with subordinate commanders during flight.

The CASPAN – equipped with ten airline-style seats, four LED screens, ruggedized laptops and headsets – provides yet another advancement to the Devil Brigade, and will allow them to maintain real-time comms during Airborne operations and exercises, like next Spring’s Defender 20 in Europe.