POINT MUGU, Calif. — The Army is hunting for top talent to fill the ranks of specialized units for multi-domain operations, following the first one standing up last year in Washington state.

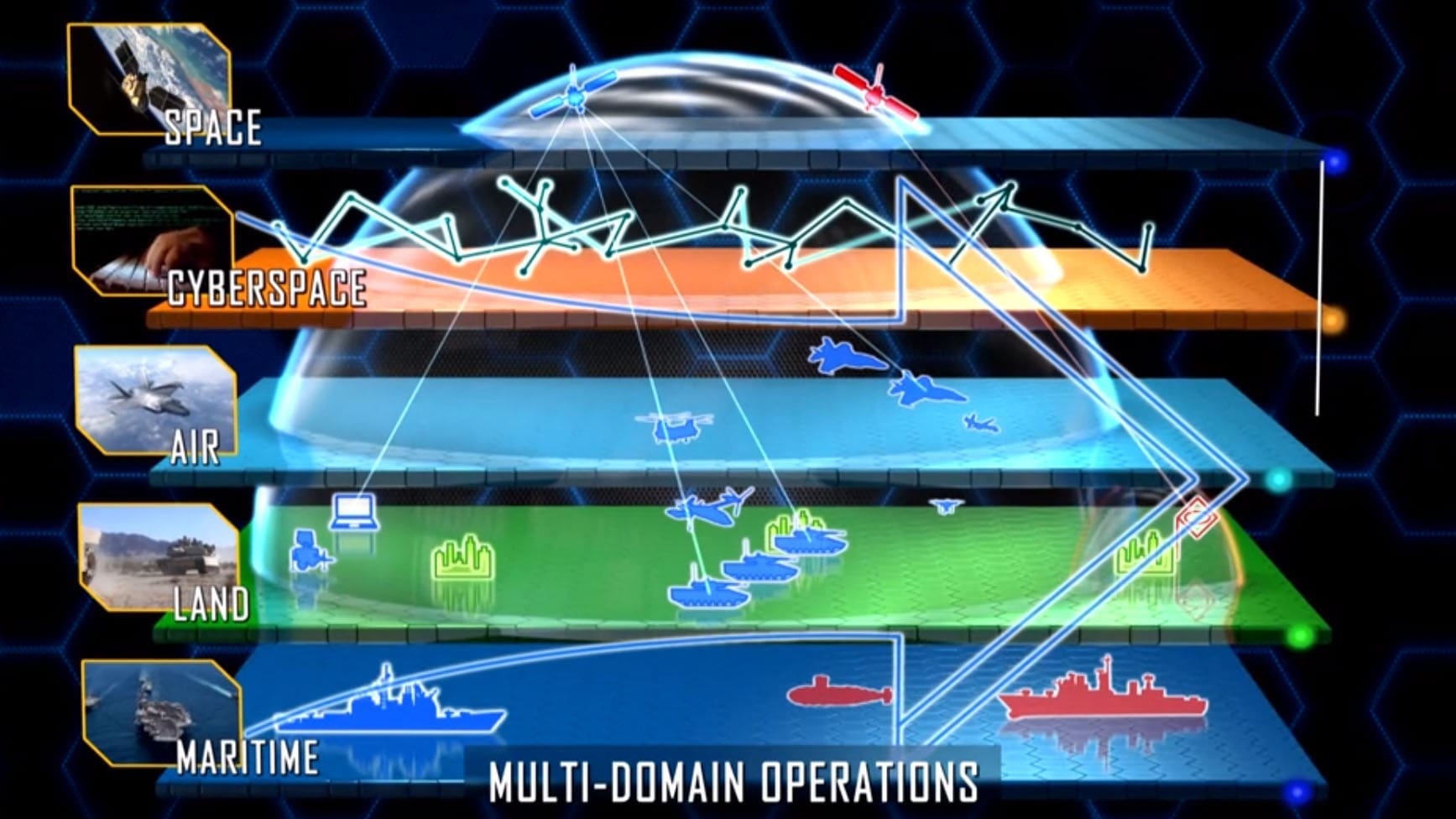

In 2019, a mixture of the Army’s space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities was activated as a cohesive unit called the Intelligence, Information, Cyber, Electronic Warfare, and Space Battalion — or simply I2CEWS.

The battalion has become “the centerpiece of the Multi-Domain Task Force,” Gen. John M. Murray, commander of U.S. Army Futures Command, said Tuesday during the Association of Old Crows virtual EMS Summit.

Located at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, the battalion combines non-lethal Army capabilities with kinetic capabilities, such as missile defense. The I2CEWS operates in support of U.S. Army Pacific, and AFC has “plans to stand up more as we begin to experiment with this formation,” Murray said.

The Multi-Domain Task Force is a model of how the Army envisions joint-warfighting on future battlefields against near-peer competitors, like Russia and China. Before the Army activates additional formations, though, Murray said it will first need the right talent to fill the ranks.

“The No. 1 thing is finding talent, and I’m convinced we have some of that talent already in our ranks,” Murray said. “And we’re going to have to go into our recruiting pools to find some of that talent. The Army is already beginning to explore innovative ways in talent management.”

Some innovative talent management programs include the Assignment Interactive Module 2.0, or AIM 2.0. The information system is a way for officers to build detailed resumes and take part in a market-style hiring system for their next assignments as organizations post specific positions they are looking to fill.

Talent management will also be part of the Integrated Personnel and Pay System-Army, or IPPS-A, a web-based human resources system already adopted by the National Guard, that will soon integrate the Army’s personnel, pay and talent management functions into one secure web-based application.

Much like how traditional battlefields will change under the information age, the Army will also recruit talent differently. For example, Murray explained, “Thirty-eight years ago, when I was offered a four-year Army ROTC scholarship, they couldn’t care less what I majored in.

“So, I picked the easiest major I could find,” he admitted. But today “we’re offering [cadets] a six-year scholarship to come out with a degree the Army needs, and if they can’t meet our requirements, then they’re not going to join the Army.”

The Army has taken other steps to attract and keep cyber talent, such as hosting cyber hackathons, boosting pay and incentives, and direct commissioning.

But “the most attractive way to retain our cyber warriors is the thrill of the mission. To be honest, [cyber warriors] are doing things they could not do outside the Army without spending time in jail,” Murray said, regarding cyber warfare missions.

Cyber warriors direct and conduct integrated electronic warfare, information, and cyberspace actions. They are responsible for the aggressive defense of Army networks, data infrastructure, and cyber weapons systems.

For Murray, who is responsible for leading a team of more than 24,000 Soldiers and civilians in the Army’s modernization enterprise, helping shape the Army’s future force is personal.

The four-star talked about his eight grandchildren, especially one granddaughter who, he believes, will one day be “an infantry commander wearing airborne and Ranger tabs.” It’s her generation he’s working for, he said, not “old Soldiers like me.”

Murray wasn’t the only one with that mindset.

“I use some of the same equipment my father used, and my nephews are now flying some of the same equipment that I flew,” said Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood, director of hypersonics, directed energy, space, and rapid acquisition.

“We need our grandchildren to fly new and modernized equipment as we continue to go forward,” Thurgood added. “So to those of us that have aged a little bit in the process of our careers, it is personal, because we spent that time with our Soldiers, and we spent that time with our families.”

In the end, that’s really what AFC and “the whole team, to include our acquisition partners, brings to our Army, delivering solutions that our Soldiers need when they need it,” Murray said.

“This is about our kids and our grandkids that will defend this great nation going into the future,” he added. “That’s really what personalizes this mission for me, and that’s a heavy rucksack to carry.”

By Thomas Brading, Army News Service