During the summer of 1918, as World War One ended, the Austrian Navy suffered a series of defeats at the hands of the Royal Italian Navy, which was based in Genoa. The most powerful ships of the Austrian Navy withdrew to the Adriatic Sea port of Pola to avoid capture. Enemy ships could not enter the harbor because of floating booms and barricades designed to encircle and destroy their targets. The Italian Navy attempted several attacks on the Austrian fleet at Pola. Still, it could not penetrate the sophisticated harbor defenses in any of them.

Raffaele Paolucci was an Italian Naval surgeon who devised a plan to infiltrate the harbor at Pola and destroy the largest ships of the Austrian fleet. He was killed during the operation. Even though the sheltered enemy fleet appeared impenetrable to conventional attack, Lieutenant Paolucci had the idea that he might be able to reach the Austrian ships by simply swimming to them with explosives in his possession.

“If I could be dropped off near the entrance to the harbor, a swim of three kilometers would enable me to reach my destination,” Paolucci concluded after consulting charts depicting the Pola estuary.”

Paolucci began training to swim alone into the harbor at Pola while keeping his plans a secret from his friends and family. Evenings and weekends were spent swimming in the lagoons of Venice, building up his endurance to the point where he could comfortably swim five miles without stopping. To simulate the weight of an explosive charge he planned to carry with him to destroy the enemy ships, Paolucci began dragging a 300-pound barrel of water behind him as his stamina grew.

Paolucci presented his plan to his commanding officers in May, confident in his ability to carry out his vision for the military. He was informed of the apparent dangers associated with such a venture. Still, he was instructed to continue with his training.

Paolucci was introduced to Major Raffaele Rossetti in July, who impressed him. In his investigation, Paolucci discovered that Rossetti had designed and built an entirely new type of aquatic weapon. This manned torpedo was ideal for the mission for which he had been preparing himself.

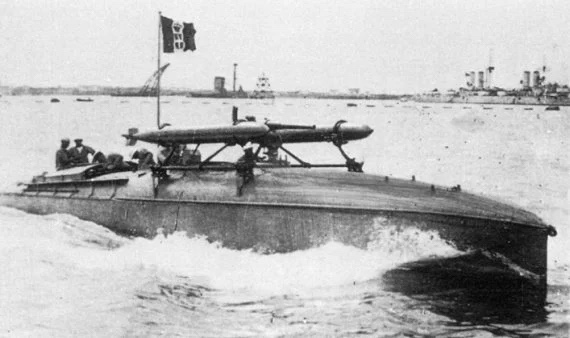

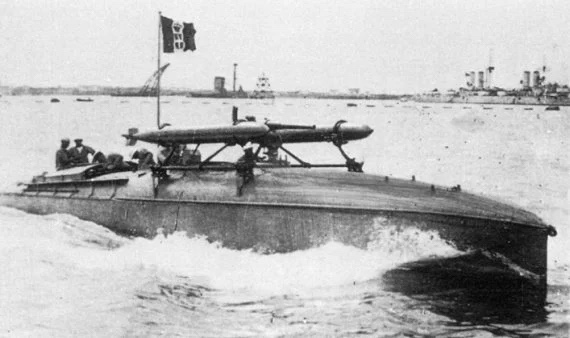

An unexploded German torpedo shell that had washed up on the Italian coast had inspired Rossetti to design and build a sleek submersible craft that could be pulled through the water like a horse, using the long, slender shell as a frame. Rossetti’s rebuilt torpedo was about 20 feet long, weighed one and a half tons, and could propel a pair of riders through the water at a top speed of two miles per hour. It was filled with compressed air that drove two small, silent propellers, powered by compressed air. Located at the front end of the apparatus were two detachable watertight canisters with a capacity of 400 pounds of TNT, each of which could be detached and transported separately. The craft’s position in the water could be changed by adjusting a series of control valves that Rossetti had devised.

Swimming and guiding the torpedo were practiced in the Italian naval shipyard in Venice, where Rossetti and Paolucci worked. Paolucci later wrote, “We had to be in the water clinging to the machine, which moved slowly; we had to steer it with our bodies, and in some cases were forced to drag the apparatus ourselves…we habituated ourselves to remaining in the water for six or seven hours at a stretch with our clothes on, and to passing unnoticed beneath the eyes of the sentries posted along Venice dockyard’s perimeter.”

An Italian navy motorboat brought the two men and their hybrid watercraft to within a few miles of the entrance to the harbor at Pola on the night of 31 October 1918. Rossetti and Paolucci slipped into the water, mounted their torpedoes, and set out to sabotage the Austrian fleet, which was utterly unaware of what they were getting themselves into.

Rossetti and Paolucci submerged the torpedo by riding the incoming tide until only their heads were visible above the water’s surface. They left for Pola at 10:13 p.m. on a Friday. Assuming everything went according to plan, Rossetti estimated that it would take no more than five hours to deliver the explosives to the Austrian ships and return to the waiting Italian motorboat, which was safely anchored away from the sight of Austrian patrol boats.

Rossetti turned off the air valve driving the torpedo’s twin propellers on their way into the harbor, preventing them from being sucked into it. The torpedo was carefully guided up to the first of the barriers that guarded the outer harbor by the two men who had guided it up. The enemy’s searchlights swept across the water, threatening to reveal them to the public. The searchlights passed over them despite their repeated appearances without disclosing their location.

When Rossetti and Paolucci arrived at the outermost barricade at 10:30 a.m., they discovered that it was constructed of “numerous empty metal cylinders, each approximately three yards in length, between which were suspended heavy steel cables.” “….. In the meantime, the two men lifted and pushed their boat over the obstacle, fearful that the sound of metal scraping against metal would alert Austrian guards on the other side of the water. Their efforts went largely unnoticed. “After a great deal of effort,” Paolucci wrote, “we were able to get past the obstruction when I felt myself being seized by the arm.” After a moment’s thought, I realized Rossetti was pointing to a dark shape that appeared to be moving toward us.” They were completely unaware of the presence of an Austrian U-boat, which was gliding past them and out into the Adriatic Sea without using its lights and with only its conning tower above the water.

The two men steered the torpedo slowly toward the seawall that protected Pola’s inner harbor after restarting the torpedo’s motor. While Rossetti waited in the shadow of the seawall, Paolucci swam ahead to find the quickest way into the port. Rossetti was a little late. Instead, he encountered another stumbling block in the form of a gate constructed of heavy timbers studded with long steel spikes.

Paolucci returned to Rossetti’s boat and informed him of his discovery. Rossetti decided to proceed with the mission. It was now against the tide, and the two men had to fight against it to drag the massive torpedo up to the submerged gate. As the tide receded, Rossetti and Paolucci struggled to make their way past the nets and into the harbor where the anchored Austrian battleships were anchored. Paolucci wrote, “our endeavors proved successful.” It was 3:00 a.m. now, and the sun was shining brightly.

The dreadnought SMS Viribus Unitis, the largest ship in the fleet, was chosen as the primary target because it was closest to the shore. Rossetti and Paolucci were swimming through sleet and hail when they noticed the sky beginning to brighten with dawn. Just as they were about to reach the side of the Viribus Unitis, the torpedo began to sink unpredictably.

While Paolucci was frantically trying to keep the torpedo afloat, Rossetti discovered an intake valve that had been accidentally opened, allowing air to escape from the cylinder and sinking the ship. After closing the valve, the two men took a few moments to relax in the shadow of the Austrian flagship. According to Paolucci, “this was unquestionably the worst of all our trying moments.”

They reached the Viribus Unitis at 4:45 a.m. after making their way down a long line of Austrian battleships that stretched for miles. Rossetti detaches one of the TNT canisters from the front of the torpedo and attaches it to the hull of the Viribus Unitis, which was then launched. Rossetti set a timer for 6:30 p.m. when he planned to detonate the 400-pound charge of TNT.

As Rossetti and Paolucci pushed off from the side of the Viribus Unitis, a sentry on the flagship noticed them and alerted the authorities.

The Italians attempted to navigate towards the shore, hoping to find refuge. A boat from the Viribus Unitis was dispatched to capture them as soon as they were discovered. After quickly arming the second canister of explosives, Paolucci set it free in the ebbing tide of the river. As a result of flooding the torpedo’s air cylinder, the ship sank to the bottom.

A group of sailors from the Viribus Unitis apprehended the Italian officers and transported them back to the ship. They were shocked to discover that the Austrian fleet had mutinied during the previous night and that the Austrian admiral had transferred command of the Viribus Unitis to a Yugoslavian captain named Ianko Vukovic. Having been ordered ashore, all German and Austrian crew members were escorted off the ship, leaving the fleet in the care of neutral Yugoslav sailors.

It was 6:00 a.m. at the time. Because Rossetti was aware that the TNT would detonate in half an hour, he informed Captain Vukovic that his ship was in “serious and imminent danger.” “Save your men,” says the captain. Captain Vukovic demanded an explanation calmly. “I’m not going to tell you when, but the ship will be blown up in a short time,” Rossetti said.

Vukovic didn’t waste any time, yelling in German, “Men of the Viribus Unitis, save yourselves and everyone else you can!” “The Italians have smuggled bombs aboard the vessel!” When the Yugoslavian crew members learned of this, they panicked and abandoned the ship. As Paolucci described it, “we heard doors open and shut quickly, we saw half-naked men rushing about madly and clambering up the steps of our batteries, and we heard the noise of bodies splashing into the sea.”

Rossetti took advantage of the sudden panic and inquired of Captain Vukovic about the possibility of saving themselves. Vukovic agreed with me. Rossetti and Paolucci dashed to the side of the ship and jumped overboard. They were captured. They were quickly apprehended by a group of enraged Yugoslavian sailors in a small boat, who took them back to the Viribus Unitis, where they were imprisoned. “We were under the impression that they intended for us to perish on the doomed ship,” Paolucci wrote. The time was 6:20 p.m.

Once again, Rossetti and Paolucci found themselves surrounded by a threatening mob of sailors when they returned to the ship’s deck for the second time. They were yelling at us, claiming that we had deceived them, and others demanded to know where the bombs were hidden. Rossetti rose to his feet and demanded that he and Paolucci be treated relatively as prisoners of war, which was granted. Vukovic ordered his men not to harm the Italians, and they followed his orders.

There was no explosion at 6:30 p.m. when the time came. Neither Rossetti nor Paolucci said anything to one another, as if they were wondering what had gone wrong. Captain Vukovic was still attempting to restore order on the ship’s deck when a storm hit the ship. Crewmen who had abandoned the Viribus Unitis rowed in lifeboats all around the ship, unsure whether to flee to safety or return to the ship as the ship sank.

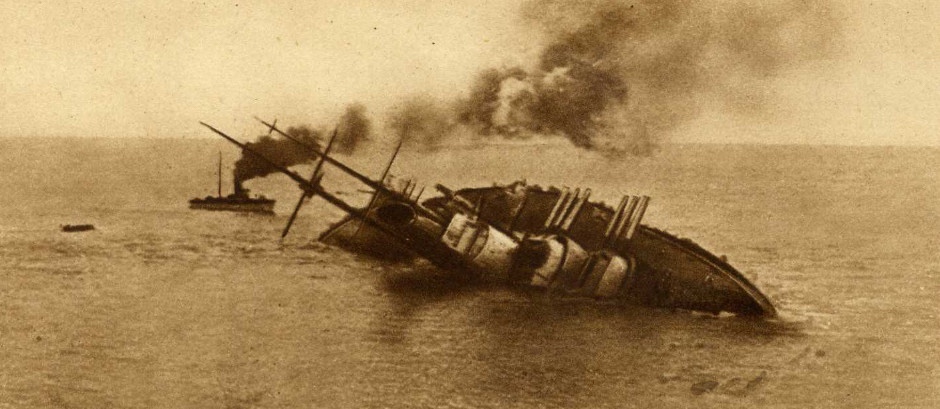

The TNT charge exploded at 6:44 p.m. local time. When the delayed explosion occurred, Rossetti and Paolucci were taken aback by how quiet it was, describing it as “a dull noise…a deep roaring, not loud or terrible, but rather light.” Instantaneously, however, a massive column of water rose into the air at the ship’s bow and splashed down on the ship’s forward deck. In the aftermath of the explosion, Rossetti and Paolucci requested permission to abandon the ship once more out of shock. Captain Vukovic shook their hands and pointed to a rope they could use to escape into the water, motioning for one of the lifeboats to come and pick them up from the water.

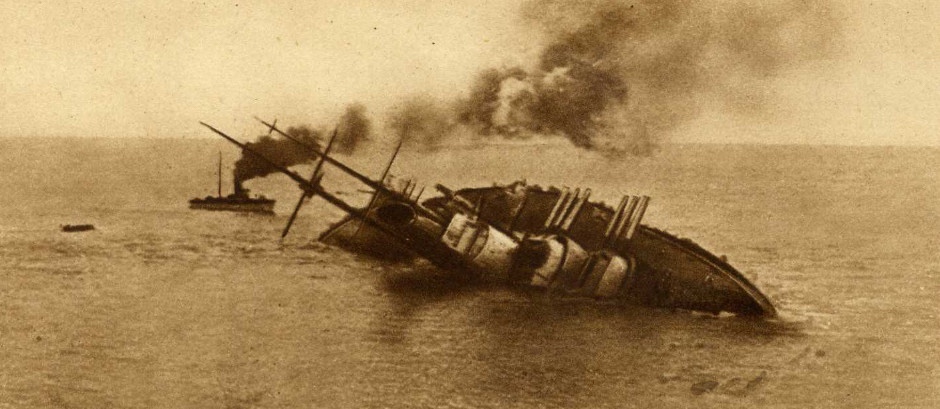

When Rossetti and Paolucci were dragged onto the small boat, they turned to watch the Viribus Unitis sinking into the water. In his book, “The Viribus Unitis,” Paolucci describes how the ship began to heel over more and more until the water reached the level of the deck and the ship capsized utterly. I noticed that the massive turret guns were being tossed around like toys. Towards the keel, I noticed a man crawling until he reached the top of the ship. It was Captain Vukovic who made the announcement. He died a short time later after being struck in the head by a wooden beam while attempting to save his life by swimming to shore after having extricated himself from the whirlpool of water.” Rossetti and Paolucci were transported as prisoners of war to an Austrian hospital ship for their recovery. There, they discovered that the second canister of explosives, which had been set free by Paolucci just before they were apprehended, had exploded against the hull of an Austrian ship named Wien, causing it to capsize and sink.

Italy and Austria signed a peace treaty three days later, on 4 November 1918, bringing the war to an end. The following day, the Italian fleet seized control of Pola, allowing Rossetti and Paolucci to be released from captivity. The two gentlemen were presented with gold medals in recognition of their bravery. Rossetti received a reward from the Italian government of 650,000 lire as compensation for his services. “A war adversary who, in dying, left me with an ineradicable example of generous humanity,” he said of Captain Vukovic’s widow when he presented the reward. Widows and mothers of other war victims received the funds used to establish a trust fund for them.

croatian-treasure.com/viribus