Earlier this week, A-TACS developer Digital Concealment Systems released their new FG variant for use in forest green environments. Immediately, potential users offered their critique. “This pattern is too green.” “That pattern is too tan.” We’ve heard comments running the gamut. But remember, camouflage is an illusion and the point of the trick is to make something disappear. The problem is that the only constant is the camouflage itself.

Regarding camouflage, this is the most general rule. The more specialized a camouflage is, the less utility it provides. What does this mean? It means, camouflage has to be relevant to the environment it is pitted against. For example, you could have the most perfect of camouflage, making yourself out to blend in like a bush in the desert. But the second you move, you no longer blend in. You might have a great desert camo suit but the second you get near water, everything turns green and you stick out.

This was the point of the holy grail of camouflage, the so-called universal camo pattern. Unfortunately, the pattern the US Army decided to call UCP is anything but. Instead, we’ve all seemed to latch on to something that is in fact the great compromise; Crye Precision’s MultiCam. It blends in to every environment at about the 70% level across the board. A true universal pattern isn’t designed to be perfect in any one environment but rather to be “ok” in ALL environments.

The lesson here is that, while well intended, the adoption of multiple specialized patterns guarantees that Soldiers will inevitably find themselves in environments where their uniform becomes a hindrance rather than a help.

The problem isn’t new. We’ve seen it time and time again.

Many may not know this but the so-called ERDL camouflage pattern adopted by the US military at the end of the Viet Nam conflict actually had two variants; a green and a brown dominant version. This is because Viet Nam wasn’t all jungle but rather consists of multiple micro environments. There are the brown dominant central highlands and the verdant jungle areas. Unfortunately, the supply system had trouble making sure that the right uniform was on the right guy for the right environment. In fact, issues with different patterns infiltrated all portions of the supply chain. There are examples of the ripstop poplin jungle fatigues that were manufactured using both pattern variants in a single garment! Unfortunately, this isn’t the last time that has happened (right SJ?)

Then, there’s the recent past. Prior to the adoption of UCP, the US Army relied upon Woodland and Desert camouflage patterns. All Soldiers were issued Woodland clothing and equipment regardless of posting. The 3-Color Desert pattern was considered specialty equipment and only issued to select personnel based on operational requirements. Unfortunately, during 1991′s Operation Desert Storm many American troops wore Woodland clothing due to the shortage of desert issue. Ten years later, this same situation was repeated during the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom and what’s worse, once again during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Unlike post-9/11 operations, the military had ample time to procure and issue specialized desert clothing and equipment prior to the commencement of hostilities with Iraq, yet they failed to accomplish that task. Consequently, we had troops that wore a combination of Desert and Woodland clothing while some received no desert issue at all. The concept of universal camouflage was envisioned to overcome these issues. One pattern for clothing and equipment so that Soldier’s could deploy at a moment’s notice, anywhere in the world.

Most recently, we’ve seen British troops dying their desert uniforms with green dye in order to blend in better with areas of dense vegetation in Afghanistan. Issues like this have caused the US Army to develop a family of patterns strategy with a base pattern sharing a common geometry of shapes yet with different color palettes for different environments.

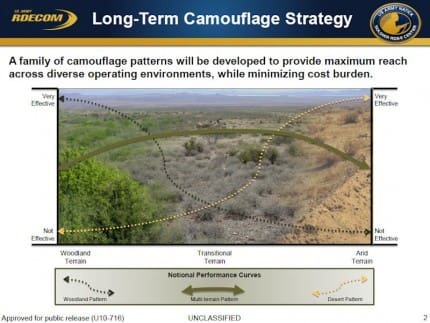

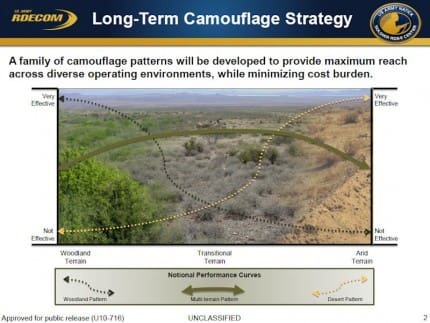

While dedicated camouflage patterns are fantastic in the environment they are designed for, they work against the Soldier in other environments. As you can see in this graphic shown at the Industry Day conference, the Army has learned that Soldiers in Afghanistan traverse multiple micro environments during a single mission. If the Army adopts dedicated patterns, Soldiers will potentially be safe as houses in one micro environment, but as their mission progresses, their uniform will do the enemy’s work for him, making them stick out like the proverbial sore thumb.

Soon we will be hit with a deluge of new families of camouflage patterns. There is going to be a lot of specialization out there. All I ask is that you remember to consider your application. If you will be sitting in a hide or blind all of the time, go for a very specialized pattern but if you will be operating in a wide ranging variety of environments then look for something more generic.

It’s a real quandary isn’t it? Even if you can afford to purchase all kinds of cool patterns, how will you make sure you’re in the right pattern at the right place and time? Can you imagine having to halt during a movement so that everyone can change clothes?

You might be interested to know that Legion Firearms has recently introduced rifles in a burnt bronze color and have now perfected their own combat gray. Check out their website or like them on

You might be interested to know that Legion Firearms has recently introduced rifles in a burnt bronze color and have now perfected their own combat gray. Check out their website or like them on