This is the fourth and probably final installment of this series. Not that I have said everything there is to say on the subject, but I judge that I have said enough to get small unit leaders started on the right track. In this segment, I will be discussing leader tools already in use or available like Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), inspections, and rehearsals that can be either enablers or obstacles to effective combat load management – depending on how they are used or misused. Establishing unit SOPs, conducting systematic inspections, arranging appropriate rehearsals, and aggressively managing the load, of soldiers, teams, and unit vehicles, is leader business. More experienced senior NCOs and Officers have to take charge, set the example, and provide guidance and supervision. Smart leaders certainly do not let the burden fall on individual soldiers and our junior and least seasoned leaders to figure out by blind trial and error the best possible practices.

During every phase of the process, good leaders emphasize appropriate attention to detail (positive leadership technique) while avoiding the pitfall of inappropriate micromanagement (negative leadership technique). Admittedly, it can sometimes be challenging to recognize the difference or the line between the two. Let us start with SOPs. Keep in mind, at best, SOPs serve only to codify a unit’s pre-planned intentions or reactions to various generic combat situations. Simple, expedient drills or checklists to be employed when there is no time to do detailed planning. Therefore, at a minimum, SOPs always have some value as a baseline or starting point from which to make adjustments. Still, SOPs and doctrinal “school solutions” are just guidelines and not straitjackets. Realistic and specific mission analysis can and should be applied to validate or invalidate the general assumptions contained in SOPs in relation to pending missions.

Consequently, I have found that SOPs can be better and more functional tools for units if they are constructed and employed as relatively simple descriptive guides to action rather than applied as overly detailed prescriptive dictates. I suggest reviewing the Standing Orders for Roger’s Rangers circa 1759 as a classic example – albeit outdated. Rest assured, encyclopedic tomes burgeoning with minutia will not be read, remembered, nor followed when a mission goes south in the middle of the night in a driving rainstorm. If your unit SOP is thicker than the Ranger Handbook because it tries to cover every conceivable contingency, I suggest dedicating some smart soldiers to the task of trimming it down to a more useful size. Then, validate that leaner SOP by applying it consistently during all of the unit’s subsequent realistic training evolutions.

Even then, do not fall in love with your SOP. Even the best SOPs developed in garrison – like tactical plans – rarely survive unchanged after the first real-world contact with the enemy. Despite that reality, humans tend to cling to the familiar, and individual egos are often invested in how existing unit SOPs have been established and applied. Moreover, leaders may be inclined to extrapolate neat combat scenarios in SOPs that they would prefer to fight on paper and in training. Rather than the realistically messy and unpredictable engagements one might not want to even contemplate but are more likely to face. I know, changing on the fly is hard; but it is something a leader must be prepared to do – and do well. Real war is like that. Bottom line, Moses did not bring your SOP off a mountain on a stone tablet. Be prepared to adjust or even discard an SOP if it is not applicable to the situation at hand.

Inspections naturally complement and dovetail with unit SOPs. Ideally, inspections should always be approached as a team event and should be mission-focused, thorough but quick, and impersonal. No egos involved. Inspections – done right – are not gotcha drills. Properly conducted inspections should be designed to help the unit expediently find and correct issues before those issues become hazards to mission success. For people who have spent time in an Airborne unit, the Jumpmaster Personnel Inspection (JMPI) would be recognized as a good example of what a sound inspection protocol should look like. Granted, some units have a bad habit of padding the time required for the entire pre-jump process, but JMPI itself is rarely anything but efficient and effective.

This would be a good time to talk about uniformity. Again, JMPI provides a good template in my professional opinion. In JM School – at least when I went through in the early 80s – we practiced the prescribed inspection sequence over and over and over again. For the first several days no deficiencies were intentionally rigged onto the jumpers. That was so that we could work on our precision first. Speed would come naturally over time. Most importantly, it also meant that we learned by repetition what right looked and felt like. That way, when deficiencies were eventually introduced in the jumpers we JMPIed, those issues jumped out at us, were called out with the correct nomenclature, and could be subsequently corrected expeditiously.

The inspections by every JM were uniformly conducted; likewise, parachutes are identically packed by Riggers and then donned in a uniform manner by jumpers. That is true of static line as well as HALO parachutes and JMPI. Is uniformity absolutely essential? Not necessarily; a parachute is actually a very simple apparatus. As long as the activating system is properly assembled and functional, gravity and air pressure will do the rest. The parachute itself can be “trash packed” – as is not uncommon with some civilian skydivers – and still probably work. But even for civilians, a reserve parachute, packed by a certified rigger, is usually required as a mandatory back up. However, unlike a civilian jumper, the military jumps as a means of infiltration, not for recreation. Mistakes do not just affect one individual.

In Airborne units, a JM is an NCO or Officer with other leadership duties. However, during pre-jump and JMPI, he or she acts as a technical expert whose focus is on one narrow but important subset of the mission – the insertion phase. As we all know, other technical experts like mechanics, medics, communicators, and armorers, all do specific pre-operational inspections and have their own important roles in getting a unit ready for a mission. Getting every jumper out of the aircraft and onto the dropzone safely is raison d’être for the JM. Indeed, in static line, mass tactical jumps, the drop altitude may be so low that a reserve might not have time to fully inflate if the primary has been improperly rigged or otherwise fails. Therefore, I would say the level of attention to detail for military parachute operations is fully justified. And, in the case of JMPI, uniformity ensures that the inspection process does not take undue time away from other critical pre-mission tasks like rehearsals for actions on the objective.

Of course, a demand for uniformity must be based on actual mission needs – not on conformity for conformity’s sake. More on that later. Rehearsals are more comprehensive, but serve much the same purpose as relatively static inspections like JMPI. Properly done, rehearsals are essentially dynamic inspections by unit leadership of the team in action. I will say that again. rehearsals are dynamic inspections. A unit will always have limited time between planning and mission execution. Therefore, rehearsals have to be prioritized. Usually, those essential “actions on the objective” tasks I mentioned earlier are done first. For bigger units like battalions and above, a large scale sandtable of the objective area and a “walk through, talk through” format is often the most practical option. Future virtual systems will digitize the process and allow leaders to avoid congregating on the battlefield but I expect these types of rehearsals will still be important.

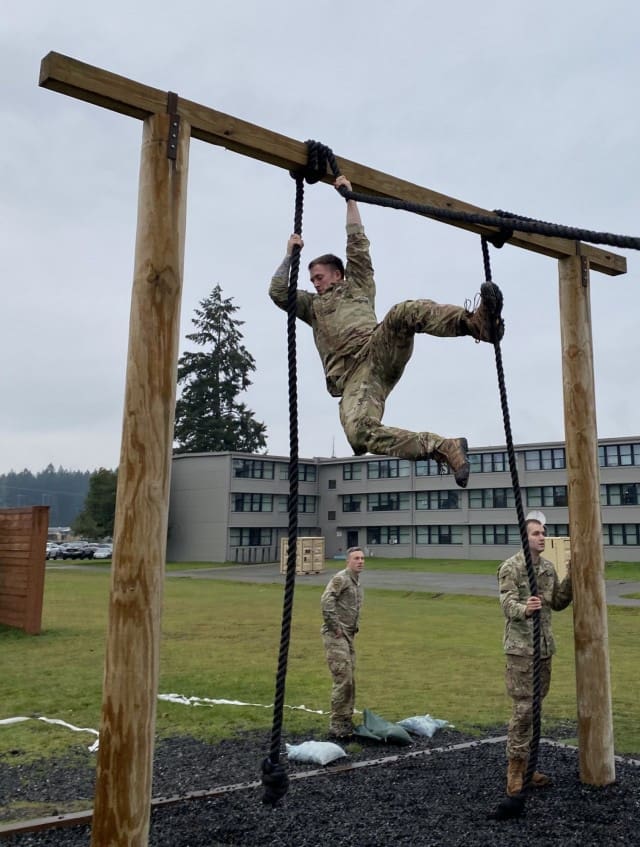

Smaller units, say company and below, likely will use a sandtable as well, but will also need to do individual and small-unit physical rehearsals of critical actions. I will use one movie reference to illustrate a fictional critical action that required priority rehearsal. As readers may recall, in The Dirty Dozen, Jimenez was the only raider who was supposed to climb the rope. Yet, every one of the dozen had to practice scrambling up the rope. Why? Because destroying the antenna on top of the chalet, and shutting down communications, was mission essential. After all, Jimenez might get killed before he got a chance to make that climb. As fate would have it, he did die and someone else made that ascent and completed that task in his place. A leader identifies those tasks – large and small – that require physical rehearsals. In turn, the leader makes sure those rehearsals are conducted to standard and as close to a “full mission profile” i.e., as realistically as time and resources will allow.

In a unit that takes training seriously, just about everything that is done in training constitutes a rehearsal. Think of first aid training. If units are doing it routinely to standard as gaged by technical experts like medics, leaders can have confidence that soldiers have the skills to do buddy and self-aid and casualty evacuations, and need not dedicate any additional time to those critical tasks before a real mission. Likewise, it pays dividends for units to consider Ruck Marches as rehearsals rather than just Physical Training events. Certainly, physical conditioning is one perfectly valid goal of the exercise; it just need not be the sole or even primary event focus. Instead, always make the extra effort to carry the real items or realistic dummy substitutes whenever possible. Think about adding time, distance, and difficulty (complex terrain), to the march rather than simply carrying the same prescribed weight over the same course every iteration.

Consider incorporating additional tactical load carriage tasks like casualty carries to the event, but do not just practice carrying notional casualties. Rather, use the opportunity to rehearse the hasty redistribution of combat loads (IAW unit SOP) within the small unit necessitated by that casualty(s). Consider having soldiers build a travois or cart with pre-positioned scraps to move a casualty longer distances. I have attached a picture (below) of some dummy load examples for those that might not be familiar with the concept. Along the left, are the “store-bought” or commonly issued training versions of a radio, grenades, and M4 magazine. Frankly, these are not often found outside of schoolhouses and centrally-run events like Expert Infantry Badge testing. Most units simply do without and, therefore, significantly short change the realism of their training.

However, with a little effort and imagination, suitable substitute training aids can be manufactured. Take for example the item at the top of the picture. A casual observer might just see a piece of a utility pole. It is that. I see a close enough approximation of a Javelin anti-tank missile. In fact, taking it a step further, I have been considering trying my hand at chainsaw sculpting and carving myself a Carl Gustav out of it. Am I suggesting that units could whittle themselves a 1:1 scale replica of a Recoilless Rifle? Yes, yes, I am. Why not? It would not have to be secured in an Armsroom. Moreover, appropriate diameter and lengths of PVC or galvanized pipe can be hacked to stand in for 84mm, 81mm, 60mm rounds, or even Bangalore Torpedoes.

Granted, people not building their own house may not have residual building material lying around like I do. However, scrap lumber and plumbing bits like these can be found on any building or demolition site every day. Contractors have to haul this stuff away all the time. If a unit offered to take some away for training purposes, I am sure that could be worked out at no cost to anyone. I have done it myself. In any case, with a little work on my table saw I was able to quickly produce a wooden radio, M4 magazine substitutes, claymore mine, blocks for 5.56 and 7.62 bandoleers, and blocks of C4 (drilled for simulated priming). If the empty bandoleers are not available, some can be fabricated from old ACU/BDU shirt sleeves. A claymore bag can be made from a pants leg. It really is not that hard.

Here are some other load management tips. Spend time training on basic fieldcraft and “survival” skills. Troopers and units need to be able to live with relative safety and comfort in the field. That means practice constructing at least hasty fighting positions and effective sleeping shelters. Individual soldiers need to know how to get the most out of their issue multi-layer clothing systems. If they have experience and confidence in their clothing that creates opportunities to leave non-mission essential clothing items behind and lighten that load. Moreover, soldiers will be able to get more quality rest – if not actual sleep – when the tactical situation permits. That, in turn, sustains the fighting strength of the unit in the longer term.

Sadly, this is a point of failure for a lot of units and it highlights uniformity and conformity gone wrong. Unit SOPs – and some lazy leaders – have a bad habit of dictating the exact items a soldier brings to the field. Then demanding that everyone wear the identical uniform regardless of the level of activity. If soldiers are properly trained, each should be able – with minimal supervision – to meter their own core temperatures by adding or subtracting layers as appropriate for their level of activity and metabolism. In a temperate zone, the risk is that a soldier will learn the hard way, spend an uncomfortable night, and do better the next time. Of course, if environmental conditions are more extreme, leaders may need to be more prescriptive about what is carried and worn. However, uniformity of a formation or unit should not ever be a factor or goal in these kinds of decisions in the field.

Likewise, as I mentioned in an earlier segment, time spent teaching soldiers how to properly use and get maximum utility out of their issued weapons can provide additional opportunities to lighten the load. Soldiers who have confidence in their ability to hit what they aim at will be less inclined to carry unwarranted amounts of ammunition or to waste ammunition spraying and praying. The unit should have even more confidence in the skills of their teammates selected to man crew-served weapons. It is extremely helpful for the rifle squads to have the chance to see the machinegunners, anti-tank gunners, and mortar crews engaging targets in live fire action as often as possible. That is true even in support units. For best results, gunners manning weapons on assigned vehicles in any unit should be the best trained and experienced available on those guns.

In conclusion, a leader always needs to consider the human animal when planning and managing combat loads. We are nature’s ultimate generalists. Whether by design or adaptation we are one of the few omnivores on the planet. Humans are capable of consuming and processing nutrients from almost anything and everything any other species can use for food. That gives us more survival options and greater range than any critter that is constrained to be only a herbivore or carnivore. Consequently, despite being inherently ill-suited to withstand extremes of heat, cold, altitude, and pressure, we have successfully adapted ourselves to live and thrive in the most austere environments of this world and beyond. Humans are certainly not fleet of foot as the cheetah, or as powerful as our simian cousin the gorilla, we cannot climb trees like a chimpanzee, nor are we natural swimmers like a dolphin. Yet, we can run fast enough, are strong enough, can climb high enough, and can swim well enough to compete successfully with all those more specialized animals in their domains. Generalization is our strength.

However, the physiological compromises that make us multifunctional animals also make us vulnerable. We stand fully erect to see danger or game farther away. Our feet and legs are well suited to walking long distances – unencumbered – in search of food. However, the small bones of the feet are relatively fragile and our joints are prone to damage from overuse or overloading. We are simply not optimized to carry extra weight for any distance. When we put a 100-pound rucksack or equivalent weight on our backs, it is an unnatural act that routinely results in stress injuries – often with permanent impacts. Unfortunately, combat demands that we do just that. That is a fact that we, as leaders, are not going to be able to change. Therefore, leaders must do everything they can to mitigate the unavoidable negative consequences of carrying a combat load. Remember, carrying a load is never the mission, it is always the means to an end, not an end in and of itself.

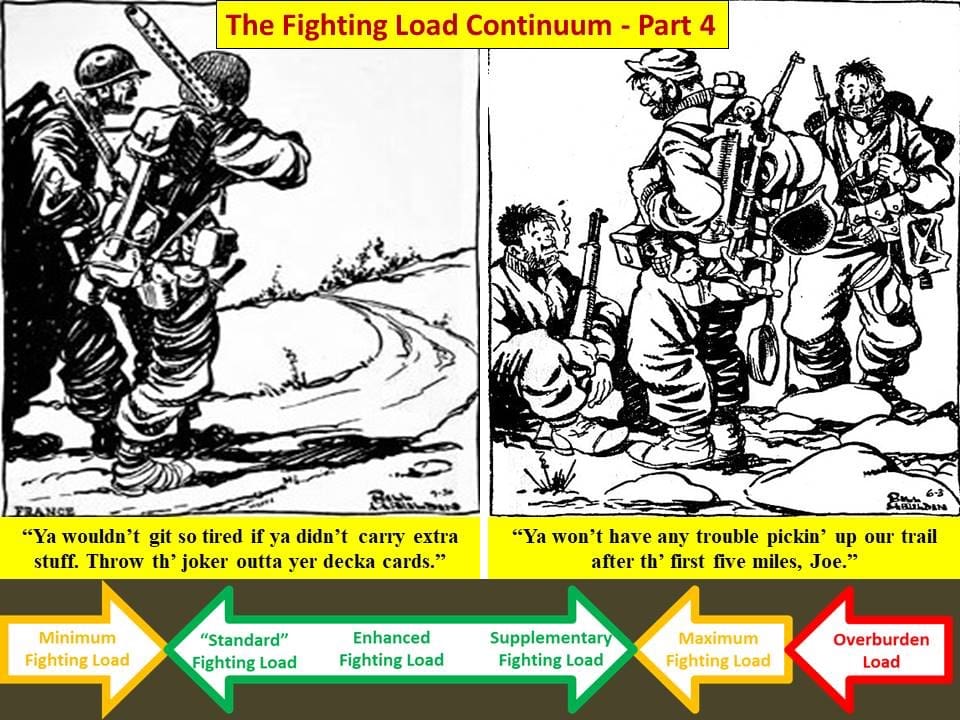

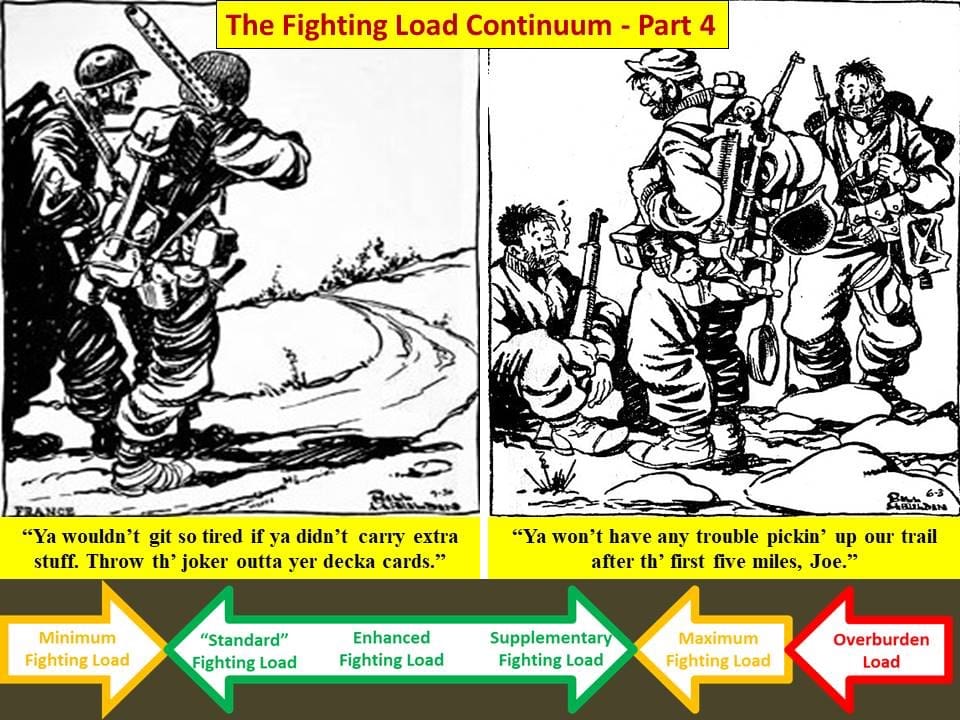

I do not expect there will be any technological solution anytime soon. Getting your soldiers the latest ruck that SOF is using is not going to change that reality either. I have seen the strongest soldiers in the world, with the latest and greatest gear, humbled by an overloaded ruck – even the “coolest” commercial versions. A leader may not be able to lighten the load appreciably on any given mission; but, can – at least – make sure soldiers only carry what is absolutely necessary and then only for as brief a period as possible. Note the Willie and Joe cartoons above. I suggest leaders internalize the spirit of Willie’s advice on the left, or risk overloaded soldiers making their own decisions and leaving a trail of abandoned gear behind as they struggle to move forward. Lots of American units have experienced that in previous wars – and it can happen again. I said in Part One of this series that there is no magic solution to managing the problems of excessive combat loads. Yet, good leadership can make any situation better. Good leadership is as close to magic as we are likely ever going to get.

-De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.