In the past, a reader or two has asked me to do an article or even a series focused on fieldcraft. At first glance, it sounded like a general topic that would be easy to write about. Then I started to think about it and realized that the subject did not lend itself to simple or short parables. Fieldcraft techniques are very situationally dependent. What a soldier does to survive and thrive in the Arctic must be tailored to that environment and, therefore, not necessarily directly applicable anywhere else. Likewise, jungle, mountain, or desert environments, and all the variations from sea level to higher altitudes demand their own unique approaches for success. Of course, urban environments also call for specific “fieldcraft” techniques.

Not to mention techniques unique to dismounted soldiers that are different than those employing watercraft, ground mobility systems, and aircraft. Over my career, I worked in all of those settings and with a good many of the aforementioned land, sea, and air, mobility platforms. I cannot claim to have fully “mastered” any, but I am informed by considerable and diverse experience. Still, I felt the need to eliminate most of the variables to keep it simple and of manageable size. It occurred to me that – regardless of the environment or the mission – there were certain tools that I always carried that I counted on to help me get the job at hand done. Some high-value utensils of fieldcraft that I could share.

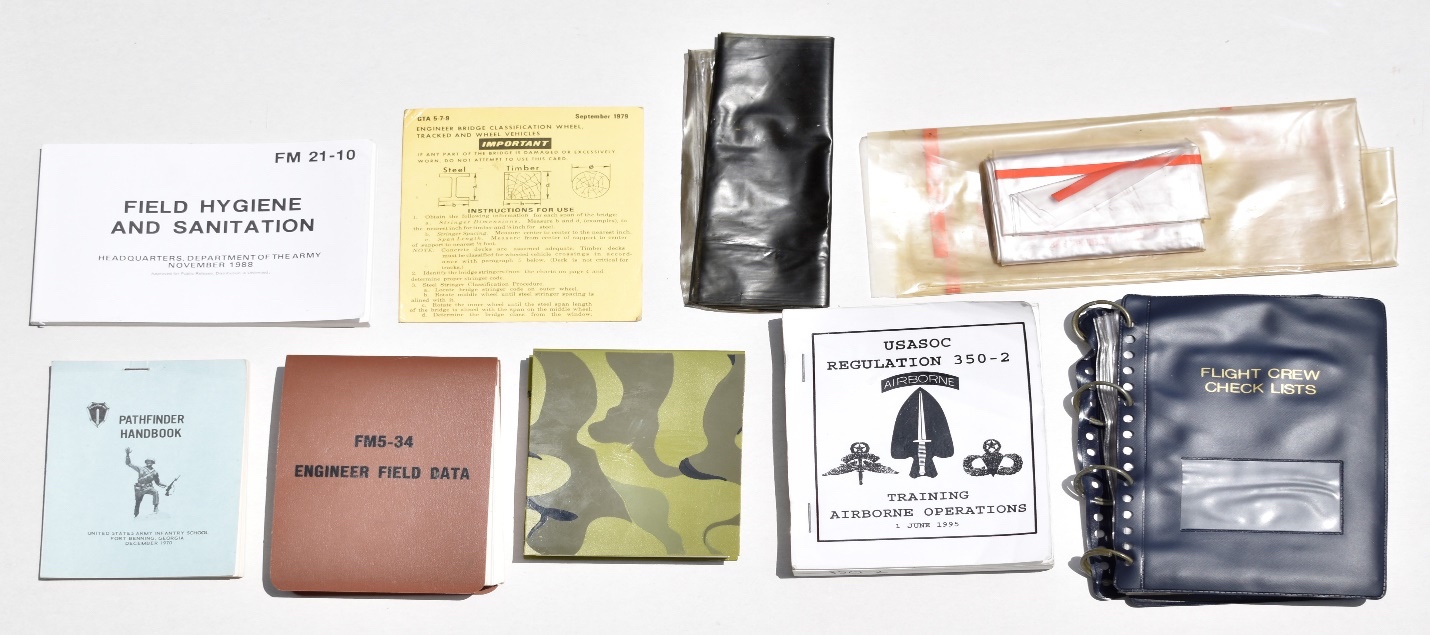

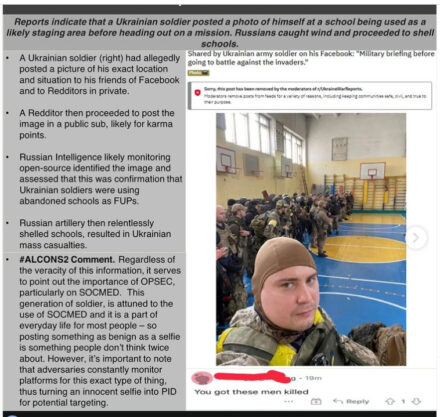

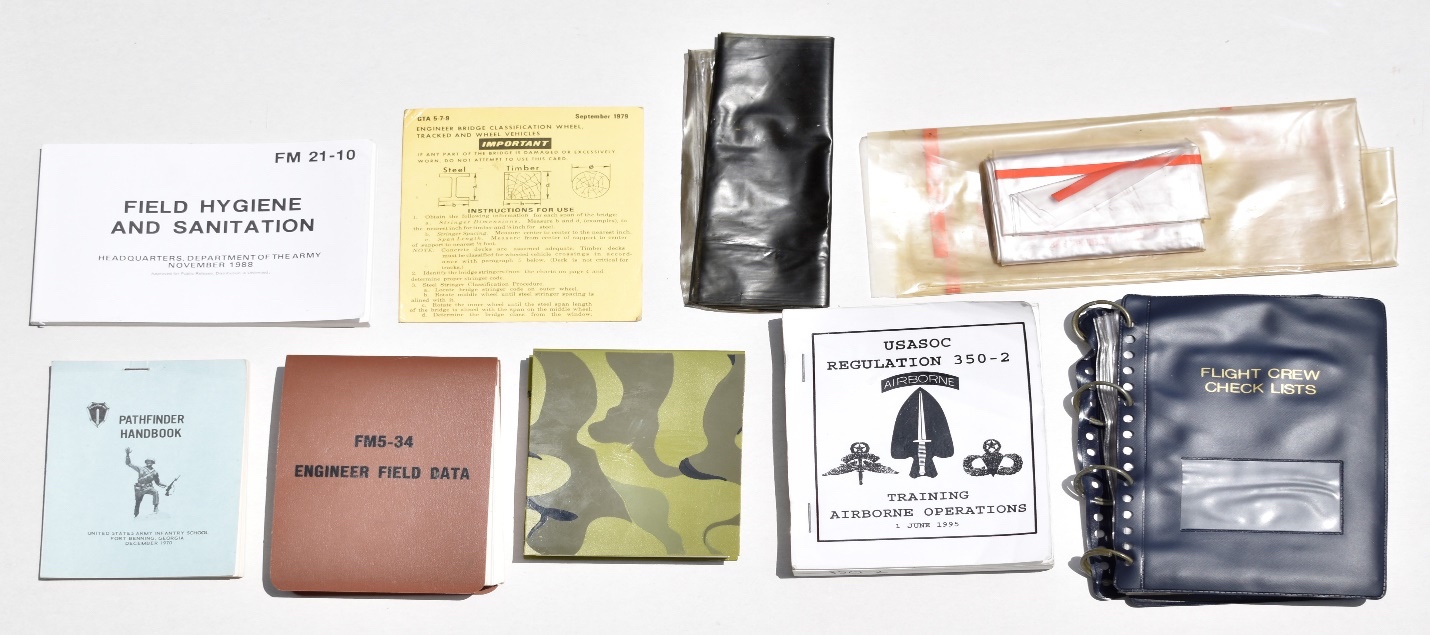

That is not to say that I could point to any individual items that I carried religiously from my first assignment to my last. But as I looked back, I realized that there were distinct types of tools that I always carried and found useful. I am going to talk about them in no particular order and provide some explanation as to what, how, when, and why, I used them. The first category would be memory aids. By that, I mean pocket-sized Reference Books and Graphic Training Aids (GTAs) that were readily available to me and other soldiers. I have a sample of some of those items in the picture below to include the Ranger Handbook (camouflage cover), Engineer Field Data, Pathfinder Handbook, Jumpmaster Duties, and so on.

When I was a Pathfinder, that handbook went everywhere with me. It had concise information on load limits and flight characteristics of various fixed and rotary wing aircraft. Checklists for sling load and rappelling operations. How to set up HLZs and DZs. Ground to air signals and radio communication protocols. In short, it had the essential tips of the trade every Pathfinder needed. Of course, through repetition, I committed much of that sort of checklist or “cheat sheet” information to memory. However, I quickly learned that when tired, or under stress, it was best not to rely on memory alone.

Case in point, the various iterations of the Ranger Handbook have been the go-to book for small unit tactics for decades. Most any Officer or NCO in a unit that does dismounted patrolling uses it as a reference. Indeed, one would be ill advised to plan a patrol without a quick review of the pointers in the book. When I was an Infantry Scout, I also started carrying the Engineer Field Data manual (Brown plastic cover). It had information on Route Reconnaissance and Bridge Classification formulas that directly supported our mission. As does the yellow Bridge GTA “whiz wheel” above it. Not to mention useful information on Demolitions, Field Fortifications, Obstacles, and even Field Sanitation, in one handy package.

Eventually, I started pulling what I considered the critical pieces out of each of the booklets, laminating them, and putting them and the GTAs into a Flight Crew Checklist ring binder (bottom right). It is simply a collection of transparent sleeves held together by metal rings. I replaced the rings on mine with grenade pull rings that would not ever come apart the way the originals sometimes did. I carried the one above for about 25 years. To protect it even more I stowed it wrapped up in a Protective Mask Waterproof Bag (top right). In the days before heavy-duty Ziplock bags, I carried the smaller handbooks in a waterproof “elephant rubber” (dark plastic top center). These “rubbers” come packed – or at least they used to – with mortar ammunition.

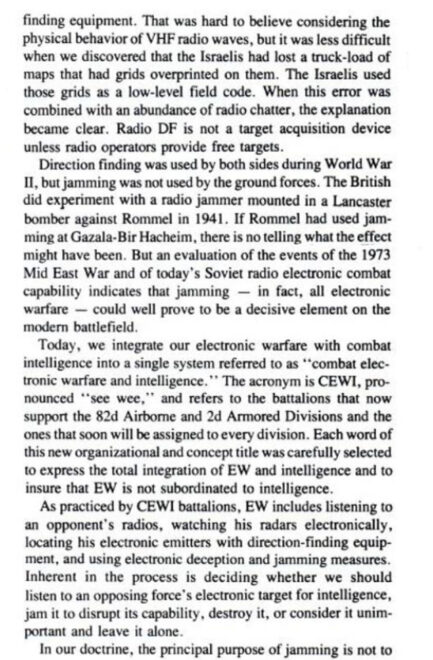

Of all the tools I carried over the years, I would expect that the concept of the “Field Knife” requires the least explanation. Soldiers have carried similar sized multipurpose blades for hundreds of years. I have several examples in the picture below. With one exception, they all have a blade that is approximately seven inches long. On the far left is that exception. It was the first knife I ever purchased in the Army. A 4-inch Buck Folder in a leather sheath that I carried on my uniform belt. I quickly found out that it was capable of doing the things that I needed a knife to do in garrison, but was too small for field tasks like cutting camouflage for an M113 APC or clearing fields of fire for a machinegun.

Moving from left to right, the next knife is the M7 Bayonet. The same blade had been introduced as the M3 Fighting Knife in WWII and as the M4 Bayonet for the M1/2 Carbine at the end of the war. The M7 version was issued with the M16 and the M16A1 Rifles starting around 1959. In Germany in the 1970s, the M7 Bayonet was issued virtually every time we drew our weapons from the Armsroom. The one in the picture is the latest version still being produced by Ontario Knives. It is strictly a stabbing weapon. Optimized for the thrust attack on the end of a rifle. It is still a good blade shape for that purpose. However, it is not well suited for those common field tasks I mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Next is the classic “Kabar” style knife. In this case, the more Army friendly Camillus “Fighting Knife” without any USMC logos. When I went down the street from an Infantry to an Aviation Battalion, I was introduced to the Shotgun News – the printed eBay of the day for all things tactical. As soon as I saw the Kabar, I ordered one. It was my first true Field Knife and I have measured every knife since then against it. Cutting camouflage or clearing fields of fire were no longer a problem. I have owned a number of these knives over the years. The first 3 or 4 I broke. Mostly because I kept throwing them at trees when I was bored – or having knife throwing competitions with my buddies. It was not designed for that. Funny, since I stopped throwing them at trees, I have not broken one since.

When I got to Fort Lewis – my first real Stateside assignment – I discovered that there were stores off post that catered to soldiers’ tactical needs. Stores with knives. So, when I saw the Gerber in one establishment’s display case, I had to have it. It looked aggressive. Exactly what a “Fighting Knife” should look like. I liked wearing it on my web gear. But, not surprisingly given the blade shape, it was not a very good Field Knife. I had paid about $70.00 for it so I did not put a big investment like that away immediately. Still, a few months later, I gave up and went back to the trusty Kabar. That is the knife I carried for three years in Hawaii. Then I got to Bragg in 1983, and I found out that Fayetteville had even better stores. Including one that had Randall knives in stock. $300.00 later I owned a Model 18. I carried this one for several years. It is not as easy to sharpen as the Kabar but otherwise, it is a top-of-the-line Field Knife.

Briefly, after the M9 Bayonet was issued with the M16A2 to the 82nd, we started carrying it to the field. It had been sold not just as a Bayonet but also as a multifunctional “Field Knife.” It is not as good a bayonet as the M7, but it actually is a fair Field Knife. Certainly, on par with the old Kabar. The biggest problem, in my opinion, was that the scabbard was too heavy. It was made of excessively thick plastic, had a sharpening stone glued on, and a “wire cutting” lug mounted on the bottom. Plus, it came with a pouch for an M9 pistol magazine. Given a more lightweight sheath option without the accessories, I think more soldiers would have had a favorable opinion of it – or maybe not. The M9 is still the standard issue Army bayonet.

This timeframe (mid-1980s), was also the era of the Army’s “Light Infantry” experiment and I started to actively look for something a little lighter than my Randall. Second from the right, I found an Ek knife that was exactly what I was looking for. Light, simple, strong, and with the “right” blade shape for a Field Knife. I carried this knife through the Q-Course and my next several SF assignments. I probably would have carried it till the end. Except that the Yarborough Knife came along. I picked mine up at the SF Museum the first chance I had. Serial number 0058. I considered just storing it at home and taking some other easier to replace knife overseas. Taking it to combat meant that I had to accept the fact that it might very well get lost or destroyed. Nevertheless, I wanted to see for myself if it was a good Field Knife. I ended up carrying it on duty, exclusively, for the next nine years. I have had no issues or complaints.

One last point about sheaths or scabbards. Most knives I have owned originally came with a leather or nylon web sheath. Some are very well made. Yet, I was never satisfied with them. Leather doesn’t do well in wet conditions, especially if exposed to salt water. Moreover, both leather and web sheaths did not offer great protection for the knife because they tended to be flexible. Practically none offered “positive” security for the knife without straps/snaps that always seemed to get in the way when trying to resheath the blade. The M9 Bayonet scabbard came with two straps. With that in mind, I had a Kydex sheath made for the Ek when I got it and one for the Yarborough (far right) as well. They worked great for me. So much so that I have since bought similar sheaths for almost all of my old fixed blade knives including the Kabar.

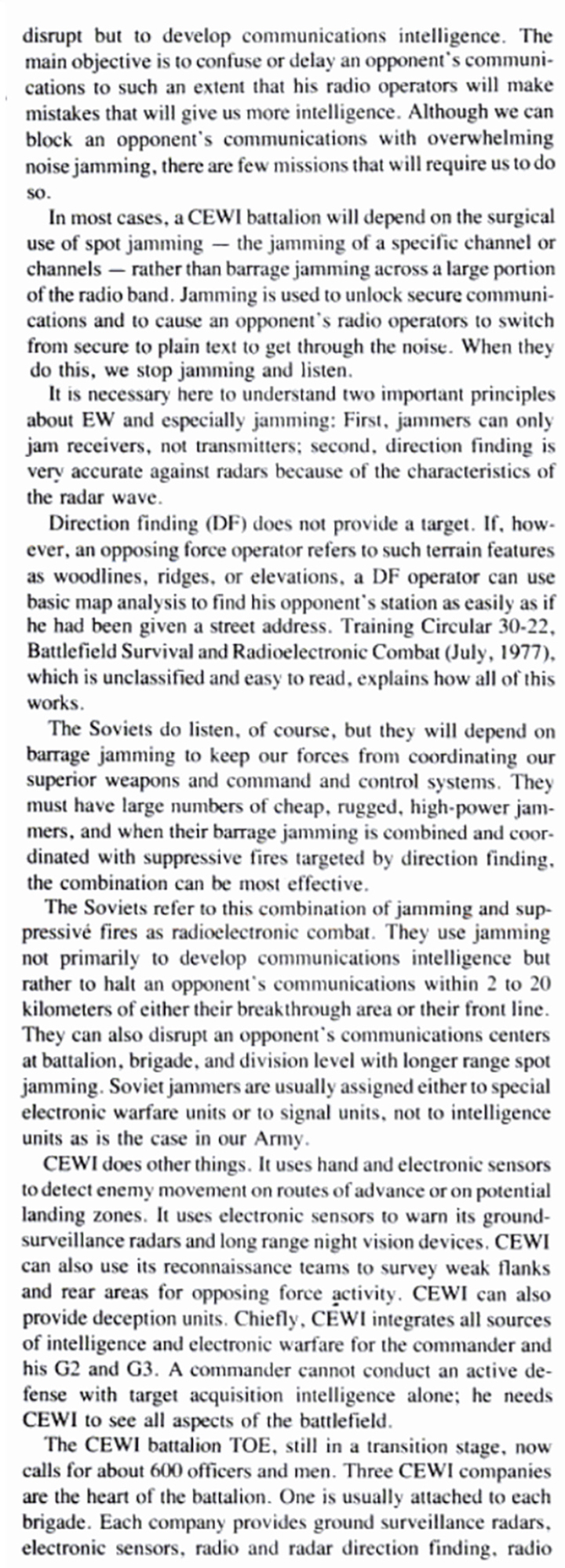

Signal devices would be another major category of tools I always needed. When I was designated to be the RTO for my Weapons Platoon Leader in Germany in 1975, I learned that the radio was not simply a means of communication. It really was a leader’s primary weapon – and, together, we were that weapon’s crew. As I became more senior – and, thankfully, radios became smaller – I found myself eventually carrying two IMBTRs set on multiple frequencies, with one or two other individuals, carrying larger radios to support me, within arm’s reach. Even before I retired, data transmissions were already becoming more the norm than voice transmissions. That trend has done nothing but accelerate. Technology is great, but in terms of “fieldcraft,” I am going to highlight less technologically sophisticated options that I always carried – with or without a radio. Things like signal panels, strobes, mirrors, whistles, and flashlights.

Above, I have laid out some of those items. At the base is a VS 17 Signal Panel. There are at least two versions of this panel in the inventory. The older style, dating from Vietnam, had an OD Green envelope pocket at one end that the panel could be folded into to hide the bright colors. Around the Desert Storm time frame, I started to see versions being issued without that feature. I always preferred the older type. However, I also always modified them the way I learned how to as a Pathfinder. That involved cutting off the two end strips with the snaps as shown on the far left. We then had the 550 cord tiedowns resewn on the panel. We found that we rarely used the snaps and they just made the panel a little heavier and bulkier. Granted, not much weight savings for a single panel; but, if you are carrying 12-15 of these panels – as we routinely would – it made a noticeable difference. I have carried at least one panel modified in this way ever since then. During GWOT, I added one of the smaller thermal IFF Panels (not shown) to my kit as well.

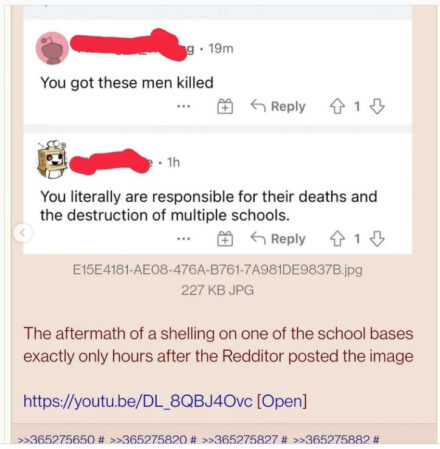

The side of the panel one chose to display depended on the light conditions and the background color. The rule was to use the side with the best contrast to the surroundings. Old timers will recognize the Fulton Flashlight on the bottom left. It was bulky, finicky, and put out about 5 lumens for half an hour on a good night. But from WWII until the mid-80s it was “state of the art” for flashlights – and was all we had. Yeah, even SOF guys. Just to the right is the Mini-Maglite that was better in just about every possible way. Yet, as far as I know, the Army never officially issued them. Instead, Soldiers bought probably tens of thousands for themselves. I do not think anyone went to Ranger School after about 1985 without buying at least one of these in Columbus, Georgia. Eventually, I started using various Surefire Flashlights (not shown) – some I bought and some were issued. After I retired, I found I had a good number of the Maglites lying around. So, I retrofitted them with LED bulbs and Lithium batteries and have them stashed in all my vehicles and around the homestead.

The Pen Flare, center, is a handy pyrotechnic signal device. Once I got issued one in 1976, I never worked without it. Signal mirrors came in glass, metal (not shown), and now plastic versions. All work well enough, glass is usually clearer, metal is the least fragile, and the plastic type can float in case you drop it in water. Whistles, left of the mirrors, come in classic military style with a “pea” or newer “pea less” versions. I have found whistles to be an indispensable leader tool many times over the years. It beats trying to yell commands during high noise events like firefights – in training or combat. A whistle can handily bridge language barriers. As long as everyone has been briefed on what a blast or two on the whistle means before the mission starts. And, of course, it is useful if one gets lost or injured. On the top right of the picture is a silk-weight orange signal panel that used to be part of an aviator’s survival kit. If weight is a real issue, or the VS 17 was left behind in a ruck, this can always be carried in a fatigue pocket and serve as an emergency ground-to-air signal.

Strobe lights (right and center) have also been Aviator and SOF issue since Vietnam. The older version (SDU-5) on the far right was eventually a 5-piece system. It came initially with a green pouch with only a 360-degree white light strobe function (bottom right). This was adequate in the days before night vision devices. To make it more unidirectional for downed piolets to use in hostile territory, a plastic sleeve with blue plastic film on one end was issued (center right). The sleeve fits over the body of the strobe for storage and was then reversed and mounted on the front of the strobe for use. It worked as designed, but was not well liked because it made the package bulkier and hard to fit into or get out of the pouch. The upper right strobe on the display has the IR Cover in place that started to be issued as NODs became more widely available. The downside was that, while invisible to the naked eye, the IR Strobe was still a light that flashed 360 degrees and would be visible to anyone else with NODs. And, no, the sleeve did not mate very effectively with the strobe if the IR Cover was in place.

The green MS2000 Strobes, just to the left of the older orange ones, came out in the late 90s. They were generally issued with the same green pouches and combined all the old functions in a slicker package. The IR cover is attached but can be flipped out of the way for a white light strobe function. The green outer casing can be extended to create the unidirectional blue light function. The green strobe on the right is fully extended. I ran into many a soldier that had no idea that feature was built in. No one had ever shown them how to do much more than turn the strobe off and on. The green strobes used common AA Batteries. The older versions used a military-specific mercury battery. Back in the day, we had to turn a battery in to get a new one. Both versions of the strobe are better with Lithium Batteries. I bought a conversion cap for the older SDU-5 and now it uses 123 Lithiums. Of course, newer, smaller versions have come out over the years. Especially for helmet mounting options. Still, these are very durable devices that reliably do the job. I have had a couple for at least 25 years and they are still soldiering on.

Let me turn now to a protective gear item. I have worn a lot of gloves over the years in cold weather situations. The old school less-than-satisfactory issue leather gloves with wool liners, for example. Those only supplied some insolation value when they were dry – and they were rarely completely dry. In colder and dryer places like Alaska, it was Trigger Finger Mittens and even bigger Arctic Mittens (not shown). They provided better insolation, but little dexterity. The modern Gloves suites that have been issued in the last 20 years or so have been much better and are routinely being changed/upgraded every few years. I have also often used “work gloves” like the issue Gloves, Heavy Duty, aka, “Engineer Gloves” for rappelling or stringing barbed wire; and even specialized staple reinforced gloves to handle concertina wire (not shown).

However, the gloves I always had with me in hot, cold, wet, and dry, conditions were the issue Gloves, Flyers, Summer or “Aviator Gloves” like those shown above. I was first issued a pair in 1976 as a Pathfinder in Germany and was never without a pair throughout the rest of my career. The most commonly available type were the ones in Air Force Sage Green with gray leather (far left). Much less common is the OD Green and black leather version adopted for Army Armored Vehicle Crewmen in the late 80s IIRC. I was gifted a pair of those at the M1 Master Gunners Course at Fort Knox in 1993. Some all-black versions were made in the 90s as well, and tan versions were issued during GWOT.

Non-Aviators who could get them, like Pathfinders and MACVSOG, started using them in the 1960s in Vietnam. Following their example, I used them in the field to protect my hands – while preserving dexterity as much as possible – everywhere else the Army sent me. Places like perpetually rainy Fort Lewis and the dryer Yakima training area, the Northern Warfare Training Center in Alaska, the Hawaiian Islands, the Philippines, winters in Korea, multiple trips to the Jungle Warfare Training Center in Panama; a dozen African countries, and even more Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries before and during GWOT. What did they protect me from? Standard risks, like red hot weapons, or vehicles and other metal objects baking in the sun. Or, conversely, in colder climes, they helped me avoid touching cold-soaked items with bare skin. I used them as inner liners for mittens in Alaska and they came in very handy for doing tasks that required more dexterity than the mittens would allow. Reloading M16 Magazines by hand for instance, or clearing a stubborn weapons stoppage, or some routine basic weapons maintenance tasks outside or in any non-heated space.

Everywhere else, they provided at least some protection against common threats like Black Palm and other ubiquitous thorny vegetation; not to mention poison oak, ivy, and the like. Of course, they also protected me from burning myself when tending a fire, or heating some chow, or grabbing a hot canteen cup or other metal containers off a stove or out of a fire. Today, I would still strongly recommend wearing similar light gloves, albeit the more modern versions that are fully touch screen compatible. One caveat, these are thin gloves by design and that means they will wear out faster with hard use than thicker and heavier alternatives. Therefore, I generally kept a couple of spare pairs on hand for contingencies.

I believe that is enough for now. I will do a Part 2 in the near future to cover other “Survival Items” and things like Multitools, Lashing Material, Navigational Aids, Machete and Axe, Weapons Maintenance Kit, Medical/First Aid Supplies, Food, and Water. Even E-Tools and Toilet Paper. As I pointed out as we went along, the things I carried evolved over time and older items were routinely replaced with newer versions as they became available. Moreover, what I carried changed based on my mission requirements. Just as a Medic will rightly have need of different tools of his trade than a Machine Gunner, so does a Leader’s essential tools rightly differ from those of a new Private. In other words, what I carried at any point in my career and talked about in the article, may or may not be specifically relevant to anyone serving today. Times change. It is the concepts and the principles behind the gear choices that are important, not the details.

De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.