“He said gorilla. Not guerrilla. Guer, go. HUGE difference kids,” Martin Harvey

A pirate is a seaman who threatens, seizes, or destroys any ship at high seas and often even harbors at the shore. Besides, they have been involved in many other criminal activities, such as piracy and the slave trade. Without any legal rights, the pirates are doing it for personal reasons. And they were regarded as criminals in all countries because those attacks were illegal acts. Piracy was punishable by death almost everywhere during the times when it was at its height. The critical difference between them and the privateers or buccaneers, about whom we can also claim that they were some sort of pirates, but not treated like criminals, is also the legality of their acts.

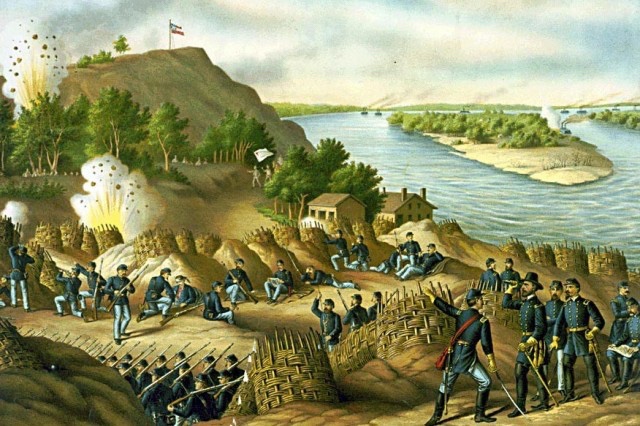

The U.S. allowed about 1,700 private warships to cruise the ocean, searching for British prizes during the Revolution, when a cash-strapped Congress could not launch an efficient navy of its own at the time. These revolutionary privateers carried congressional commissions, effectively legalized pirates, which outlawed attacks on neutral ships and prisoners’ mistreatment but otherwise allowed them free rein to rob and plunder. Most privateers were motivated by greed as much as by patriotism.

However, Washington was also outfitting a fleet of lightly armed schooners, and the debate over the navy took place in Congress. Although most members thought the idea of a navy insane, the Marine Committee was formed to oversee the production of 13 frigates.

Meanwhile, with its deep-rooted culture of fishing, shipbuilding, and ocean trade, Massachusetts considered whether to unleash its citizens by allowing state-sponsored privateering. Throughout history, governments at war have used the authority under international law to authorize independent operators to transport enemy merchant cargoes. There had already been incidents off the Massachusetts coast of scavenging looting crews abandoning ship down one side as local marauders clambered up the other side wielding clubs and cutlasses; the loot from these raids had to give them visions of bigger gains to come. To legalize privateering, the government would provide the colony with an instant navy for little to no cost.

In March of 1776, Congress followed suit and ordered that all British ships be considered “fair game for civilian warships.” After months of bitter debate on the general theme of business and patriotism, Philadelphia leaders embraced trade, going so far as to provide signed preprinted applications for commissions complete with blank spaces where names of ships, captains and owners could be inserted with minimal fuss. An early proponent of privateering, John Adams, appreciated, “I was always extremely interested in it.” Privateers had to pay monetary obligations to ensure their proper conduct under regulations. Although it is only fragmentary, incomplete information, more than 1,700 Letters of Marque were granted during the American Revolution. Approximately 800 privateers were commissioned and are frequently attributed with burning, looting, and capturing around 600 British ships.

Following congressional recognition of privateering, privateers flocked from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. Most had reputations for contraband, quirkiness, and eccentricity until this point. Most privateers just smuggled items throughout the Royal Navy’s blockade.

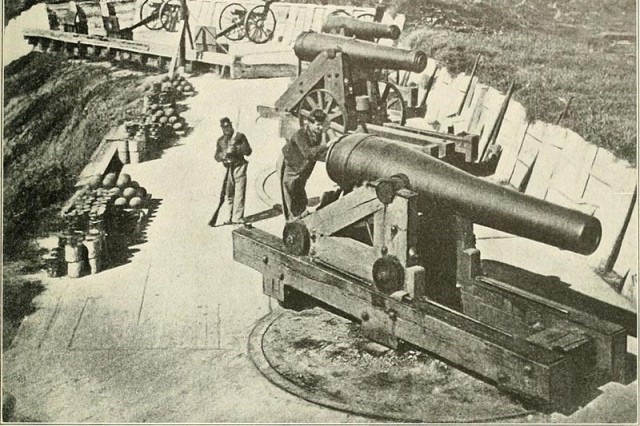

Weapons shortages resulted in delays in securing gunpowder, but some, like the Brown brothers, managed to solve the problem by converting their iron foundry to cannon-making. The Brown brothers were accused of charging ‘extortioners’ prices for guns for Congress’ frigates, giving preference to their vessels and advertising for crews with promises of quick fortunes, congenial captains, ample alcohol, and a thrilling opportunity to smite “the tyrant’s pilferers.”

Privateering was a natural fit for the brothers, and they immediately began cutting gun ports through the trade ships’ bulwarks and clearing holds to make room for more crewmen needed to sail the captured prizes home for auction. They were also named a member of the congressional committee that oversaw Congress’ frigates’ construction.

In 1777, the Ranger, an 18-gun sloop captained by a young John Paul Jones, sailed across the Atlantic with a vow “to draw off the enemy’s attention by attacking their defenseless structures,” a plan fulfilled the following spring in his daring hit-and-run raid on the British port of Whitehaven. However, Richard Grenville’s prediction that he would do infinite damage to their shipping was realized by the pirates he so loathed. While still skeptical of America’s ability to defeat them on the battlefield, the British were forced to concede one point about the rebel privateers that diplomats on the European Continent had noted in July 1776: “What is certain on the side of the Americans is their activity at sea and the ships of the Crown they are capturing.”.

In the Caribbean alone, whose position as the hub of Britain’s New World trade made it the primary hunting ground for at least a hundred New England privateers by May 1776, maritime losses reached over $2 million within a year. Royal Navy captains in the West Indies learned that a storm was approaching, but their superiors had no clue. “Time is running out,” they urged their companion, “for our journey to the English Channel.”

Before then, most American vessels carried goods such as tobacco and paper to trade for European munitions. The privateers among them were adventurous predators who might provision in French and Spanish ports but rarely sold prizes there (doing so violated those nations’ neutrality agreements with Britain), instead dispatching them back to America for appraisal and auction.

The first ship that sailed into Europe was the 16-gun Continental brig named Reprisal. Under its captain, Lambert Wickes, and carrying Benjamin Franklin to France to serve as an ambassador, the Reprisal sailed to Europe in December 1776 to join the endeavor to create an international alliance. Reprisal then set out to plunder the seas, capturing 13 merchant vessels before being chased into a French harbor by an enemy frigate.

Small privateers like Retaliation and most other ships were forced to flee before a frigate’s firepower, which could hurl a barrage of hurtling metal from up to two dozen 12-pound cannons mounted along each side. The frigate HMS Brune, for instance, destroyed a 12-gun schooner with a single broadside and significantly damaged a 9-gun schooner. In trying to treat the wounded among Volunteer’s crewmen, the boarding party found the vessel “so much damaged that we hardly had time to get them all on board before she sank.” Similarly, a Boston privateer, Speedwell, carrying 14 guns and 90 men, took a frigate’s broadside “between wind and water” (the portion of the hull usually below the waterline but exposed to the air the vessel is heeled over in the wind). The study revealed that “she was lost at sea immediately, and all her crew perished during the voyage.”

On May 17, 1777, another American captain, Gustavus Conyngham, sailed aboard Surprise with 25 men from the French port of Dunkirk and intercepted Prince of Orange, a mail steamer plying between Holland and the British port of Harwich.

In the late 1700s, British political and military leaders denounced the Revenge’s hit-and-run combat style and the many other warships now swarming European waters. For the people in Parliament, the pirates were an immoral group of terrorists to be exterminated. One report of the capture of a supply ship alleged that “rebels stripped the killed and wounded, robbed every article of clothes, bedding, and provisions belonging to the sick, burned the cutter and added every insult to the distress.” And any foe that would, “against the laws of God and Man,” fire on a vessel under a flag of truce deserved, it was declared in Parliament after one such incident, “all the horrors of rebellion,” by which was meant no mercy.

Privateers comprised two distinct ventures. A Letter of Marque permitted merchants to attack any hostile vessel they encountered along their commercial voyage. A privateer commission was issued to those who were commissioned to attack enemy merchant shipping. The primary objective was to engage a lightly armed commercial ship.

Privateers of every type of vessel were pressed into service. The largest 18th-century ship was the 600-ton, 26-gun ship Caesar out of Boston. Simultaneously, crew sizes were as little as a few men in a whaleboat and as high as 200 aboard a fully equipped privateer. Vessels designated for Privateering and Letters of Marque were launched from places up and down the east coast.

Privateers didn’t usually fly the black pirate flags; they flew a flag that looked very similar to the “Don’t tread on me flag.” Privateers that could effectively convince their opponent that the opposition was futile did the best. When that plan failed, it often resulted in extremely violent fighting with unpredictable results. Many of the pirates were captured or sank when the situation wasn’t going their way. Most did not raise the pirate flags that we know of today, but there were two basic types, Black and Red, if they did. The black was raised when you planned to raid the ship but didn’t plan on killing everyone and the Red Flag or “no quarter giving” or “the blood flag” meant they planned to kill everyone, and no mercy was to be given. It also didn’t always have to have a skull and bones. It was up to the captains what it would look like, and most pirates didn’t fly them. Those flags were used truly by pirates not necessarily by privateers.

Despite all the hardships, the crippling of British commercial shipping was highly effective, and fortunes destined to aid the founding of the new Republic were made. It is estimated that American privateers’ total economic damage was about $18 million, or about $302 million in today’s dollars during the war.

George Washington recognized early in the war that his best strategy was to “sink Britain under the disgrace and expense of war.” To survive against the formidable British military, countless small- and large-scale offensive operations needed to be conducted and maintained to keep the enemy off balance, under strain, and demoralized.

SCUBAPRO Sunday is a weekly feature focusing on maritime equipment, operations and history.