ZEROING IS NOT TRAINING

Zeroing your weapon simply calibrates your sight so that the bullet flight intersects with your line of sight at a specific distance. Zeroing has nothing to do with “Train as you fight.” Zeroing is just a Pre-Combat Check; it’s maintenance…”PMCS,” if you will. Just the same as a wheel alignment is to your tactical vehicle.

“Zeroing is not a training exercise, nor is it a combat skills event. Zeroing is a maintenance procedure that is accomplished to place the weapon in operation, based on the Soldier’s skill, capabilities, tactical scenario, aiming device, and ammunition.”

[Ref: TC 3-22.9, Appendix E Introduction]

YOU DO NOT HAVE A 25 METER ZERO

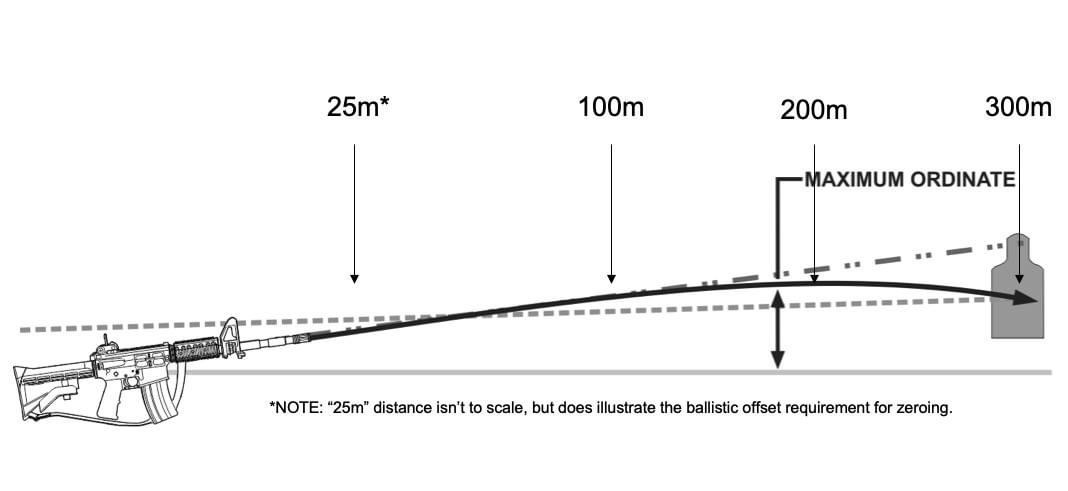

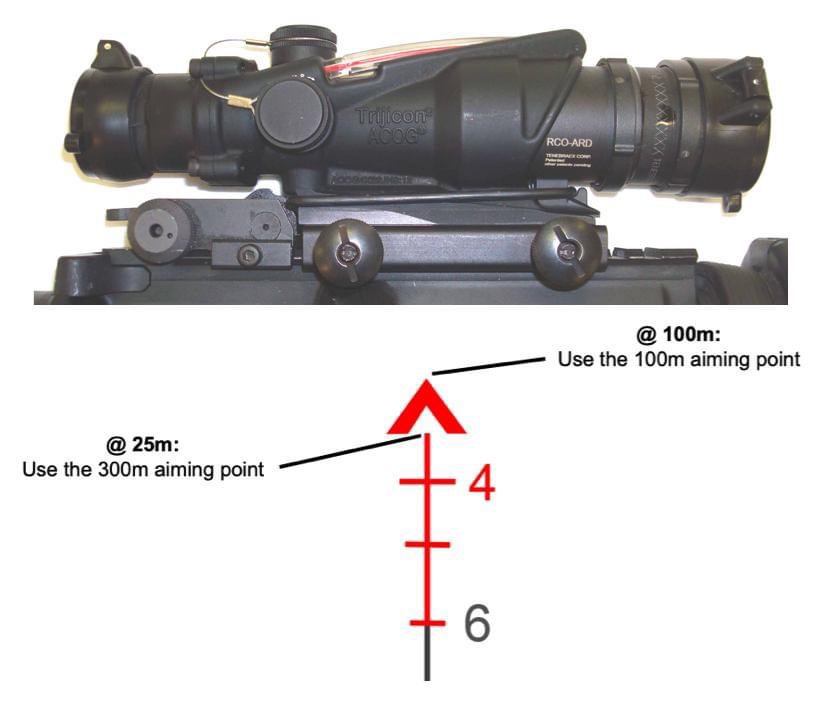

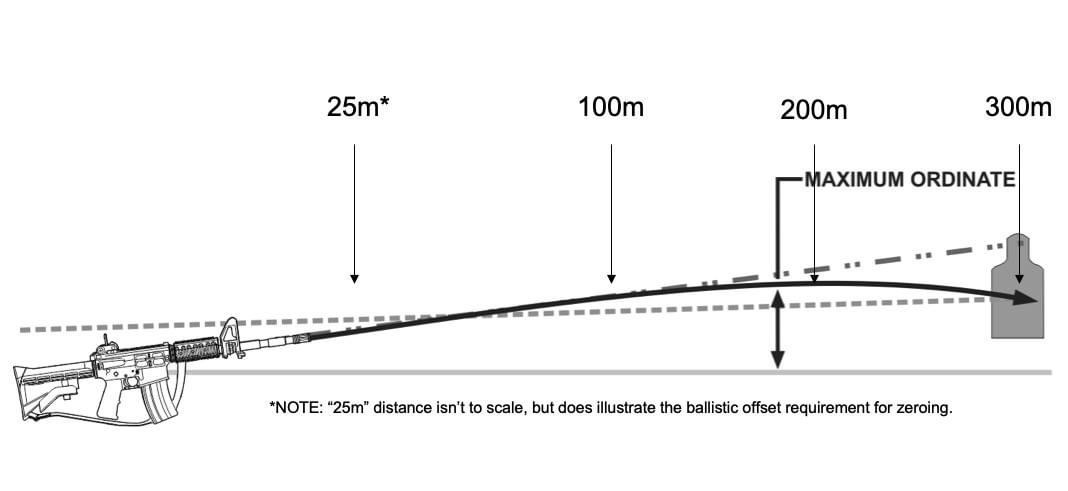

You have a 300m zero, conducted at 25m. In order for the bullet to strike where the Soldier is aiming at 300m, the bullet will cross the Soldier’s line of sight twice: once at 30m and again at 300m. The Army does not have 30m live fire shooting ranges, but it does have 25m ranges. So, what’s the work around? At 25m, the bullet is still below the line of sight (LOS), so we adjust the bullet’s point of impact (POI) to strike 1.5 MOA below the point of aim (POA). This is called a “ballistic offset.”

The same concept applies to Marines. The Marine Corps does not have a 36 yard zero. The Marines have a 300 yard zero, with a “Pre-Zero” conducted at 36 yards.

SIGHTS ARE ZEROED TO THE WEAPON, NOT TO THE PERSON SHOOTING THE RIFLE

Either the sight is matched to the bullet trajectory, or it isn’t. The person pulling the trigger can’t magically alter the exterior ballistics of the bullet. We demonstrate this reality at our Trainer courses by having cadre use someone else’s rifle with a known good zero to consistently engage targets at 300m.

[Ref: “Effects of Sight Type, Zero Methodology, and Target Distance on Shooting Performance Measures While Controlling for Ammunition Velocity and Individual Experience,” para 9(3), US Army Research Lab report ARL-TR-8594, Dec 2018.]

ZERO WITHOUT COMBAT GEAR

TC 3-20.40 removes combat gear as a condition for zeroing, recognizing that what the Soldier wears has nothing to do with the flight of the bullet, and may interfere with a solid, comfortable and unhindered shooting position needed to calibrate the weapon sight.

[Ref TC 3-20.40, Table E-14 “Conditions” vs Table E-48 “Conditions”]

“A common misconception is that wearing combat gear will cause the zero to change. Adding combat gear to the Soldier’s body does not cause the sights or the reticle to move. The straight line between the center of the rear sight aperture and the tip of the front sight post either intersects with the trajectory at the desired point, or it does not. Soldiers should be aware of their own performance, to include a tendency to pull their shots in a certain direction, across various positions, and with or without combat gear. A shift in point of impact in one shooting position may not correspond to a shift in the point of impact from a different shooting position.” [Ref: TC 3-22.9, para E-14 Note.]

REMOVING SIGHTS WON’T LOSE THE ZERO

“Removing and reinstalling the CCO or RCO will not lose the sight zero. Soldiers must record the sight serial number and the rail slot it was mounted in to retain the zero, however.” [Ref: TC3-22.9, para 3-26.].

We demonstrate this capability at our Unit Marksmanship Trainer Courses by swapping CCOs and RCOs multiple times onto an M4A1 and consistently engage 300m targets.

ETA: Luke Wright makes a great point in his comment to this post. When given the opportunity, always reconfirm your zero after reinstalling your sights. Rails/mounts may become out of spec over time and adherence to sight mounting procedures becomes critical. Depending on the precision required for distances and sizes of target engagements, the “acceptable” return-to-zero capability becomes a little squishy.

When zeroing, the following progression takes place, with a caveat*.

MECHANICAL ZERO

Sight windage and elevation knobs are centered within their ranges of adjustment in order to offer a reasonable chance of hitting the A8 25m zero target.

According to the M4A1 military specification (MIL-C-71186), mechanical zeroing will only get rounds somewhere in a 22”x16” box around your 100y aiming point. At 25m, that’s a 6”x4” impact zone. This clearly isn’t a valid zero, BUT it will get the Soldier on the A8 25m zero target.

10M LASER BORE-LIGHTING

Sight windage and elevation setting that accounts for the bullet’s trajectory at 10m that approximates a 300m zero to offer a better chance of hitting near the point of aim on 25m A8 zero target.

Laser bore-lighting is not an effective zero. For the CCO, a 10m bore-light only gives the Soldier about a 50% probability of hit at 200m. For night aiming lasers, a bore-lighting only gives the Soldier a 50% probability of hit at 150m. This, too, is clearly not a valid zero, BUT it will get a Soldier on the A8 25m zero target:

“The purpose of the bore-light is to get ‘bullets on paper’ during live-fire zeroing. Bore-lighting is not the same as zeroing the weapon.”

[Data and quote from “Training Lessons Learned on Sights and Devices in the Land Warrior Weapon Subsystem,” Army Research Institute, November 1999]

*CAVEAT – MECHANICAL ZERO & 10M LASER BORE-LIGHTING:

Unless a weapon was re-barreled or a new weapon sight was issued, the mechanical zero and laser bore-lighting should be bypassed. There’s no reason why the weapon sight setting would have changed since the last time it was zeroed at true distance during your last range event.

Since neither a mechanical zero nor a laser bore-lighting accurately applies a weapon zero, conducting those steps again will simply undo the previously validated weapon zero.

“25M ZERO”

First, you do not have a 25m zero. You have a 300m zero. In fact, the Army does not conduct a “25m Group & Zero Event.” The Army conducts “Table 4 – Basic.” “Zeroing” at 25m is applying a windage and elevation sight setting that approximates the trajectory of a 300m zero to maximize the chances of hitting the point of aim on a 300m target. Sometimes called a “near-o,” since it’s not truly a zeroed weapon, just “nearly,” and the Army uses a 25m range to get close to the first crossing (the “near” side) of the bullet with the shooter’s line of sight.

Soldiers must not rely on a 25m “zero.” Small errors at 25m create big errors at 300m. For example, a ½” sight error at 25m will cause approx. 6” error at 300m, which is more than halfway to missing your target (the E-type silhouette width is 19.5”).

CONFIRMATION OF ZERO AT TRUE DISTANCE

Small inaccurate sight settings that go unnoticed at 25m are fully expressed at farther distances. Confirmation of zero at 300m will expose those inaccurate sight settings and allow the shooter to obtain a proper and true zero.

While a 25m range is utilized to apply sight settings for a 300m zero, weapon sights are still not considered zeroed. Confirmation at true distance must take place.

Confirmation can be accomplished in any of the following ways, arranged in order of preference from most- to least-preferred.

Location of Misses and Hits (LOMAH) has acoustic sensors and digital plots of exact bullet impacts, giving Soldiers precise feedback to apply a true zero. It’s fast and it’s easy. Unfortunately, the Army doesn’t equip every firing lane or range with LOMAH. Not yet, anyway.

Known Distance (KD) range, with “spotters” inserted into each bullet hole on the paper target so Soldiers can adjust their sights to hit exactly where they’re aiming. Most Army training installation don’t have a KD range, though, so this isn’t a universal option. When available, though, this is preferred over the next option.

Automated Range Facility (ARF)/Modified Range Facility (MRF) with targets set to “hit-bob” mode react when a bullet strikes anywhere on the 300m E-type silhouette (19.5” x 40”). This method DOES NOT allow the shooter to apply a precise sight setting since no precise feedback is given. A strike anywhere on the target will register as a hit. Did you hit the target in the shoulder? Maybe the hip? Nobody knows. This does satisfy the Army requirement to confirm a true distance zero, however.

Bottom line: mechanical zeroing and laser bore-lighting help to get rounds on paper at 25m, which helps to get rounds reasonably well on target at 300m, which finally allows the shooter to get a true zero.

This is the first of a series of posts about the zeroing process. A recent post revealed a surprising amount of misinformation and mythology about zeroing in the Army, so we’re tackling the issue block by block. We’ll break down concepts and application for the entire process in future posts.

By SSG Ian Tashima, CAARNG Asst State Marksmanship Coordinator