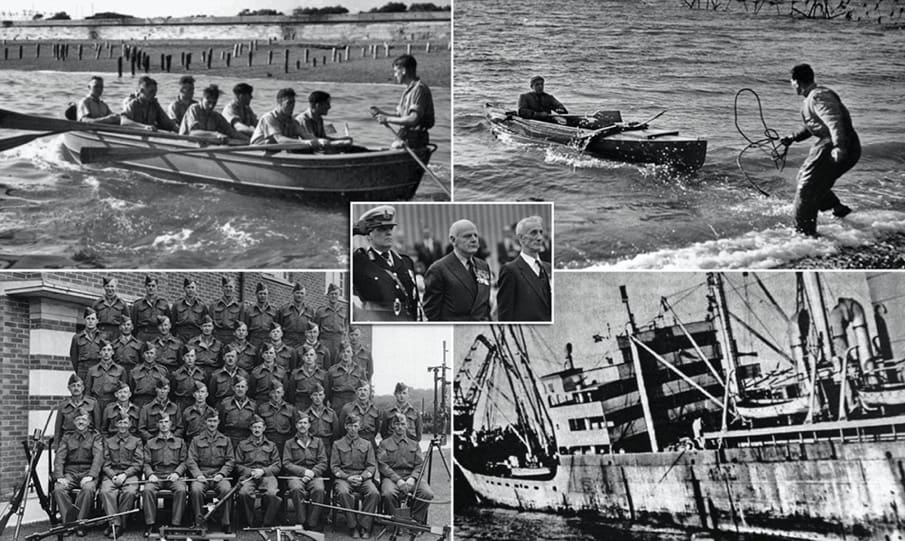

Operation Frankton was a commando raid designed to disrupt the shipping of the German-occupied French port of Bordeaux in southwest France during World War II. The raid was carried out by a small Royal Marines unit known as the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD), part of Combined Operations, now known as the Special Boat Service. They planned on using six canoes to be taken to the area of the Gironde estuary by submarine. They would then paddle by night to Bordeaux. They would attack the docked cargo ships with limpet mines and then escape overland to Spain on arrival. Twelve men from no.1 section were selected for the raid, including the commanding officer, Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler, and with the reserve Marine Colley the total of the team numbered thirteen. One canoe was damaged while being deployed from the submarine, and it and its crew, therefore, could not take part in the mission. Only two of the ten men who launched from the submarine survived the raid: Hasler and his no.2 in the canoe, Bill Sparks. Of the other eight, six were executed by the Germans, while two died from hypothermia.

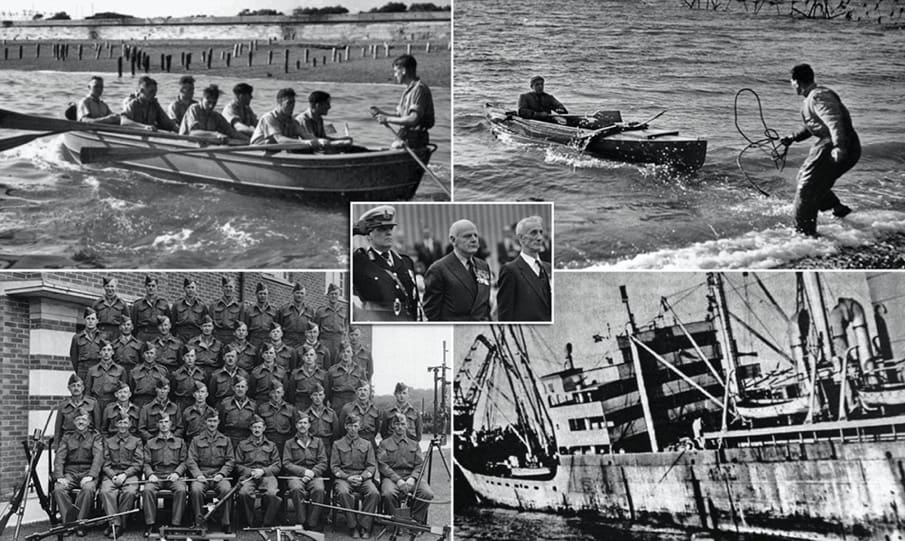

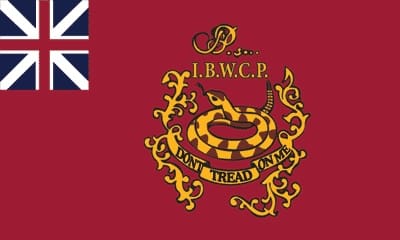

The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed the mission shortened the war by six months. The words of Lord Mountbatten, the Commander of Combined Operations, are carved into a Purbeck stone at Royal Marines Poole (current headquarters of the SBS): “Of the many brave and dashing raids carried out by the men of Combined Operations Command none was more courageous or imaginative than Operation Frankton.” The Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD) was formed on 6 July 1942 and is based at Southsea, Portsmouth. The RMBPD was under the command of Royal Marines Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler, with Captain J. D. Stewart as second in command. The detachment consisted of 34 men and was based at Lumps Fort, and often exercised in the Portsmouth Harbor and patrolled the harbor boom at nights.

The Bay of Biscay port of Bordeaux was a significant destination for goods to support the German war effort. In the 12 months from June 1941 – 1942, vegetable and animal oils, other raw materials, and 25,000 tons of crude rubber had arrived at the port. Hasler submitted a plan of attack on 21 September 1942. The initial plan called for a force of three canoes to be transported to the Gironde estuary by submarine, then paddle by night and hide by day until they reached Bordeaux 60 miles (97 km) from the sea, thus hoping to avoid the 32 mixed Kriegsmarine ships that patrolled or used the port. On arrival, they hoped to sink between six and 12 cargo ships then escape overland to Spain.

Permission for the raid was granted on 13 October 1942, but Admiral Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, increased the number of canoes to be taken to six. Mountbatten had initially ordered that Hasler could not take part in the raid because of his experience as the chief canoeing specialist but changed his mind after Hasler (the only man with experience in small boats) formally submitted his reasons inclusion. The RMBPD started training for the raid on 20 October 1942, which included canoe handling, submarine rehearsals, limpet mine handling, and escape and evasion exercises. The RMBPD practiced for the raid with a simulated attack against Deptford, starting from Margate and canoeing up the Swale.

Mark II canoes, which were given the codename of Cockle, were selected for the raid. The Mark II was a semi-rigid two-man canoe, with the sides made of canvas, a flat bottom, and 15 feet (4.6 m) in length. When collapsed, it had to be capable of negotiating the submarine’s narrow confines to the storage area then, before it was ready to be taken on deck, erected and stored ready to be hauled out via the submarine torpedo hatch. During the raid, each canoe’s load would be two men, eight limpet mines, three sets of paddles, a compass, a depth sounding reel, repair bag, torch, camouflage net, waterproof watch, fishing line, two hand grenades, rations, and water for six days, a spanner to activate the mines and a magnet to hold the canoe against the side of cargo ships. The total safe load for the ‘Cockle’ Mark 2 was 480lbs. The men also carried a .45 ACP pistol and a Fairbairn-Sykes Fighting Knife.

The men selected to go on the raid were divided into two divisions, each having its own targets.

· A Division

· B Division

A thirteenth man was taken as a reserve, Marine Norman Colley.

Mission

On 30 November 1942, the Royal Navy submarine HMS Tuna (N94) sailed from Holy Loch in Scotland with the six canoes and raiders on board. The submarine was supposed to reach the Gironde estuary, and the mission was scheduled to start on 6 December 1942. This was delayed because of bad weather en route and the need to negotiate a minefield. By 7 December 1942, the submarine had reached the Gironde estuary and surfaced some 10 miles (16 km) from the estuary’s mouth. Canoe Cachalot’s hull was damaged while being passed out of the submarine hatch, leaving just five canoes to start the raid. The reserve member of the team, Colley, was not needed, so he remained aboard the submarine with the Cachalot crew Ellery and Fisher.

According to Tuna’s log, the five remaining canoes were launched at 1930 hours on 7 December. The plan was for the crews to paddle and rest for five minutes every hour. The first night, 7/8 December, fighting against strong cross tides and crosswinds, canoe Coalfish had disappeared. The surviving crews encountered 5 feet (1.5 m) high waves, and canoe Conger capsized and was lost. The team consisting of Sheard and Moffatt held on to two of the remaining canoes, which carried them as close to the shore as possible, and had to swim ashore. The teams approached a significant checkpoint in the river and came upon three German frigates carrying on with the raid.

Lying flat on the canoes and paddling silently, they managed to get by without being discovered but became separated from Mackinnon and Conway in canoe Cuttlefish. On the first night, the three remaining canoes, Catfish, Crayfish, and Coalfish, covered 20 miles (32 km) in five hours and landed near St Vivien du Medoc. While they were hiding during the day and unknown to the others, Wallace and Ewart in Coalfish had been captured at daybreak near the Pointe de Grave lighthouse where they had come ashore. By the end of the second night, 8/9 December, the two remaining canoes, Catfish and Crayfish, had paddled a further 22 miles (35 km) in six hours. On the third night, 9/10 December, they paddled 15 miles (24 km), and on the fourth night, 10/11 December, because of the strong ebb tide, they only managed to cover 9 miles (14 km). The original plan had called for the raid to be carried out on 10 December, but Hasler now changed the plan. Because of the ebb tide’s strength, they still had a short distance to paddle, so Hasler ordered them to hide for another day and set off to and reach Bordeaux on the night of 11/12 December.

After a night’s rest, the men spent the day preparing their equipment and limpet mines, which were set to detonate at 21:00 hours. Hasler decided that Catfishwould cover the western side of the docks and Crayfish the eastern side.

The two remaining canoes, Catfish and Crayfish, reached Bordeaux on the fifth night, 11/12 December; the river was flat calm, and there was a clear sky. The attack started at 21:00 hours on 11 December. Hasler and Sparks in Catfishattacking shipping on the western side of the dock placed eight limpet mines on four vessels, including a Sperrbrecher patrol boat. A sentry on the deck of the Sperrbrecher, apparently spotting something, shone his torch down toward the water, but the camouflaged canoe evaded detection in the darkness. They had planted all their mines and left the harbor with the ebb tide at 00:45 hours. At the same time, Laver and Mills in Crayfish had reached the eastern side of the dock without finding any targets, so returned to deal with the ships docked at Bassens. They placed eight limpet mines on two vessels, five on a large cargo ship, and three on a small liner.

On their way downriver, the two canoes met by chance on the Isle de Caseau. They continued downriver together until 06:00 hours when they beached their canoes near St Genes de Blaye and tried to hide them by sinking them. The two crews then set out separately, on foot, for the Spanish border. After two days, Laver and Mills were apprehended at Montlieu-la-Garde by the Gendarmerie and handed over to the Germans. Hasler and Sparks arrived at the French town of Ruffec, 100 miles (160 km) from where they had beached their canoe, on 18 December 1942. They contacted someone from the French Resistance at the Hotel de la Toque Blanche and were then taken to a local farm. They spent the next 18 days there in hiding. They were then guided across the Pyrenees into Spain.

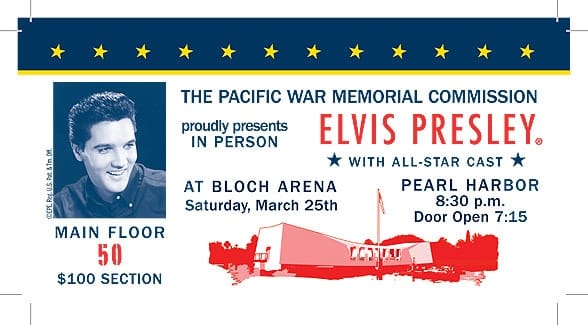

It was not until 23 February 1943 that Combined Operations Headquarters heard via Mary Lindell’s secret message to the War Office that Hasler and Sparks were safe. On 2 April 1943, Hasler arrived back in Britain by air from Gibraltar, having passed through the French Resistance escape organization. Sparks was sent back by sea and arrived much later.

Aftermath

On 10 December, the Germans announced that a sabotage squad had been caught on 8 December near the Gironde’s mouth and “finished off in combat.” It was not until January 1943 that all ten men on the raid were posted missing in the absence of other information until news arrived of two of them. Later it was confirmed that five ships had been damaged in Bordeaux by mysterious explosions. This information remained until new research of 2010 revealed that a sixth ship had been damaged even more extensively than any of the other five reported. This research also revealed that the other five vessels holed were back in service very shortly afterward.

For their part in the raid, Hasler was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and Sparks the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM). Laver and Mills were also recommended for the DSM, which could not be awarded posthumously, so instead, they were mentioned in despatches.

Of the men who never returned, Wallace and Ewart were captured on 8 December at the Pointe de Grave (near Le Verdon) and revealed only certain information during their interrogation, and were executed under the Commando Order, on the night 11 December, in a sandpit in a wood north of Bordeaux and not at Chateau Magnol, Blanquefort. A plaque has been erected on the marked bullet wall at the Chateau, but the authenticity of the details on the plaque has been questioned; indeed, given the evidence of a statement by a German officer who was at the execution, there can be no doubt that the Chateau has no link with Wallace and Ewart. A small memorial can also be seen at the Pointe de Grave, where they were captured. In March 2011, a €100,000 memorial was unveiled at this same spot. After a naval firing squad executed the Royal Marines, the Commander of the Navy Admiral Erich Raeder wrote in the Seekriegsleitung war diary that the executions of the captured Royal Marines were something “new in international law, since the soldiers were wearing uniforms.” The American historian Charles Thomas wrote that Raeder’s remarks about the executions in the Seekriegsleitung war diary seemed to be some ironic comment, which might have reflected a lousy conscience on Raeder’s part.

After having been set ashore, MacKinnon and Conway managed to evade capture for four days, but they were betrayed and arrested by the Gendarmerie and handed over to the Germans at La Reole hospital 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Bordeaux, attempting to make their way to the Spanish border. Mackinnon had been admitted to the hospital for treatment for an infected knee. The exact date of their execution is not known. Evidence shows that Mackinnon, Laver, Mills, and Conway were not executed in Paris in 1942 but possibly in the same location as Wallace and Ewart under the Commando Order.

The attack had been planned for the fourth night, but because they were not far enough up the river, Major Haslar delayed it until the fifth night, deciding to move in closer to the target area. They continued along the river with great caution and found a lay-up position in reeds, only a short distance from two large cargo ships. In their hide position, the men worked out details of the plan of attack. With only CATFISH and CRAYFISH now available, Catfish was to take the shipping on the east bank, and Crayfish the shipping on the west bank.

Nineteen limpet mines with nine-hour fuses were placed, resulting in considerable damage to at least five large ships in the harbor. Adolf Hitler was furious. One of the cockles had been discovered, and he demanded to know how ‘this child’s boat’ could have possibly breached all German defenses and security, traveled over seventy miles at night in very rough seas and against the tide, then attacked and sank his shipping with not one of them being discovered! The answer that Hitler did not want to hear was that these ‘children’s boats’ had been crewed by well-trained, determined, and courageous, Commando raiders of the ROYAL MARINES. Major Hasler received a DSO for his part in organizing and leading the raid and Marine Sparks a DSM. The RMBPD later became The Special Boat Squadron.

The Commandos’ final task was to leave the target area undetected then make their way through France in the hope of finally reaching England. After a few miles, they went and wished each other luck, hid their cockles a quarter of a mile apart by sinking them, and headed inland. The men headed north for Ruffec in the hope of connecting with the Marie-Clare Line that operated in the Ruffec area. Contact was made, and Marie-Clare (Mary Lindell) had the men moved to Lyon while traveling to Switzerland to report their contact. A route was arranged for them to travel to the south of France, cross the Pyrenees, and return to England via Gibraltar.

CATFISH: Major Hasler/Marine Sparks reached the target area destroyed shipping. He returned home via Marie-Clare Escape Line and Gibraltar.

CRAYFISH: Corporal Laver/Marine Mills reached the target area, destroyed shipping. Last seen landing. Captured by Germans. Executed in Paris on 23 March 1943.

CONGER: Corporal Sheard/Marine Moffat capsized in a second tidal race. He was last seen swimming to shore off Point de Grave. Moffat’s body was found later. Sheard’s body was never found, presumed drowned.

CUTTLEFISH: Lieutenant Mackinnon/Marine Conway last seen off The Mole at Le Verdon. He was later captured by Germans, executed in Paris on 23 March 1943.

COALFISH: Sergeant Wallace/Marine Ewart missing near Banc des Olives after the first tidal race. Later captured by Germans and executed near Bordeaux on 12 December 1942.

CACHALOT: Marine Ellery/Marine Fisher – canoe damaged on torpedo hatch of HMS Tuna. They were unable to take part in the raid.