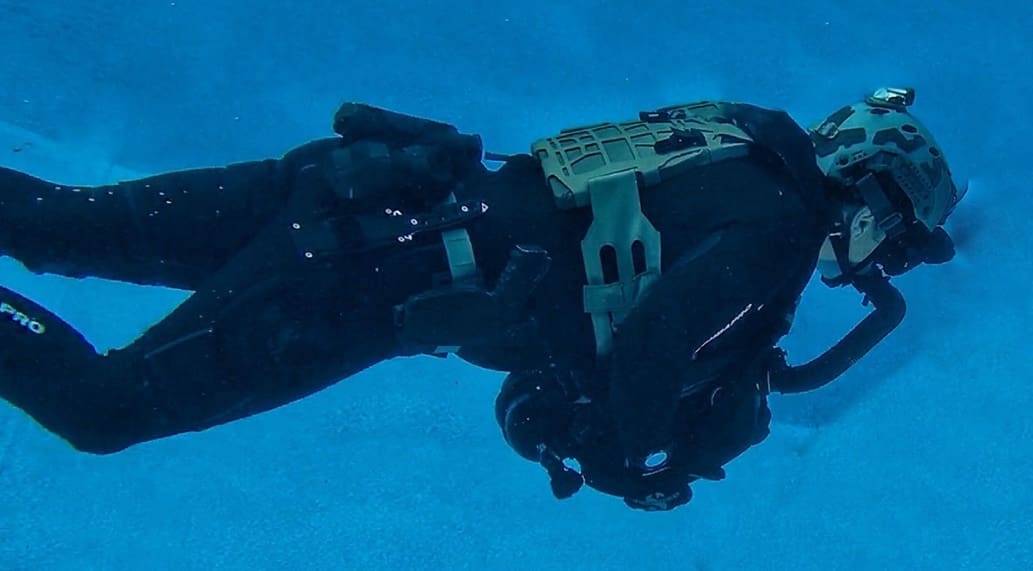

Over the past ten years or so, more and more divers have started wearing helmets when they dive. It is done for a lot of different reasons. For example, when using a Diver Propulsion Vehicle (DPV) to help protect your head if you run into something; wearing your Night Optical Devices (NOD) so when you get out of the water, you can take your mask off and pull your NODs down; for protecting your head when working around piers or doing a ship attack. You want to be ready to fight when you get out of the water, so you have your helmet on and, for some reason, people like to wear GoPros for everything they do now. But the main reason is protection for your head.

There are some things you should take into consideration before you jump into the water with your helmet on. How much protection do you need? Is it just for bump protection? If so, can you just use a thicker dive hood or do you really need something more? Let’s say you and your dive buddy are swimming along, he has his head down looking at the attack board and you are along for the ride, thinking about what you need to buy at home depot to add to your new deck you want to finish up this weekend, and then BAM!! KaPOW!! He runs into the pier cutting his head open. Now you have to buy him a steak dinner and/or lots of beer to make up for him hitting his head.

Any time you will be around piers, rocks or ships, you should have something covering your head, even if it’s just a thin dive hood. If you choose to wear a helmet, you have a few choices. Start with its physical components: does it need to be Ballistic, Non-Ballistic (glass-filled nylon or carbon fiber), or can it just be something just used for mounting gear, like the Ops Core Skull Crusher/ Head-mounted system.

Almost all helmets can be used in the water, but like everything you bring into the water, it needs to be adequately cleaned. Some companies make very cheap knock offs of different helmets. Please don’t be fooled if you pay $100 for something that would normally cost $1000. There is a good chance it won’t last that long and please for the love of god don’t do that with a ballistic helmet and then use it in war. I know looking cool is rule one, but a very close second is” don’t go dying on me” because you wanted to look cool.

All helmets used by U.S. SOCOM (sorry, bought by U.S. SOCOM) can be used in the water. If you are planning on getting out of the water and you might get in a gunfight, you might want to wear your ballistic helmet. If you are using a DPV or just need bump and scratch protection, then a non-ballistic helmet should work. If you just want to look around with your NODs when you get out of the water, a Skull Crusher works excellent. If you’re going to add lights or again you want/need to record something, then any of the above will work.

One of the issues you can have when diving a helmet is getting your mask to fit under or over. Once you have it where you want it, you can’t take it off and put it back on quickly. However, with the SCUBAPRO Odin helmet mask strap, you can attach your mask to your helmet for quick donning and doffing, when done with your dive or working around saltwater.

If you need to use a Full-Face Mask like the OTS guardian or even have a thin dive hood on, sometimes this makes buckling the chin strap a little hard. You should consider adding a chin strap extension. The extension will truly make it easier to dive your helmet; it will also help you adjust and remove it, if needed, above and below the water. Most companies make chin strap extensions for use with gas masks or other reasons.

I have had numerous inquiries about the nuts and bolts used on Ops-Core helmets and “why don’t they use stainless steel bolts so that they won’t rust?” Stainless steel does rust; it is just more rust resistant than most metals. The nuts and bolts on your ballistic helmet are ballistic bolts; they are designed not to break apart as easily if shot or blown up. So proper maintenance is required for anything you bring into the water. If you bring it into saltwater, it needs to be soaked, not just rinsed, in freshwater to get the salt crystals out. If the salt crystals are not rinsed out, they will slowly start to cut through the nylon fabric and cut it apart. This is also true for climbing ropes, harnesses, and armor carriers used in the water — make sure to clean them well. Also, always take the pads out of the helmet and make sure they are soaked in freshwater then dried.

You don’t have to take the chin strap off. Just make sure it’s dry, as well, before you store your helmet. Do not leave your helmet in the sun to dry; the sun is not suitable for anything. It is the one thing that is bad for nylon and other material like that. Leave it in a cool, dry place with air moving around and, if you can, with a dehumidifier or Damp-Rid to help pull the water out of all the webbing. Once it is dry, you can wipe the bolts with a little (a little, not a lot) of WD-40 or another type of water displacement film. Once all of this is done, you can put your helmet away or hang it in your locker. Make sure if you do put it in a helmet bag or your locker, try and have some Damp-Rid or Desiccant packs in there to help pull the moister out of your gear, as it is tough to get all the moisture out completely.

SCUBAPRO has also just launched their Professional Services webpage. It’s just a start but we hope this well show our commitment to Working divers, the Military and Public Safety Divers.

SCUBAPRO Professional Services