11th February 2026, Cadillac, MI: Avon Protection has expanded its EXOSKIN protective ensemble range with the EXOSKIN-S2 high-performance CBRN suit, designed for operators in the military, first responder and special forces segments.

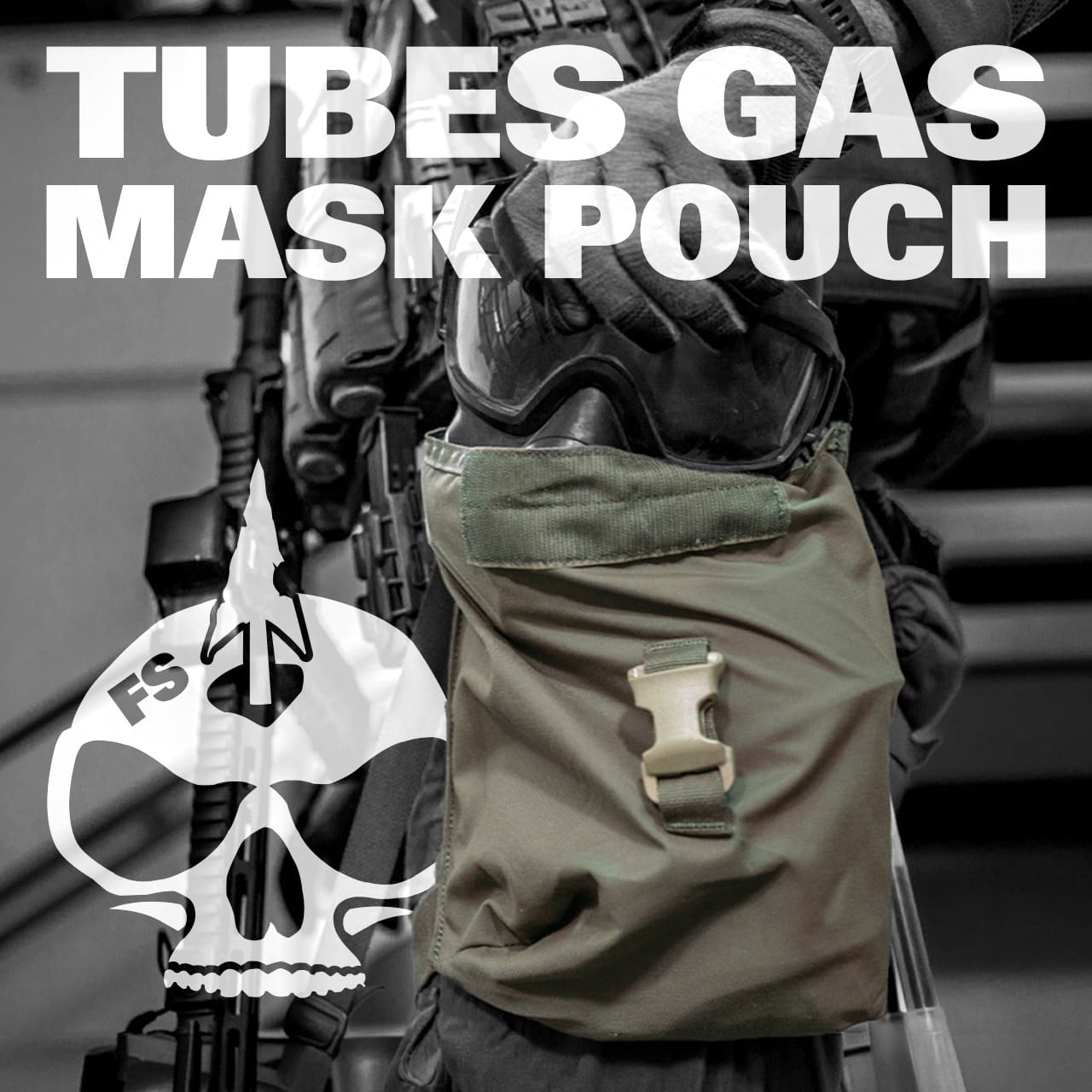

Avon Protection’s EXOSKIN-S2 high-performance CBRN suit.

With the commercial availability of the EXOSKIN-S2, users now have increased options for their protective suit requirements across the spectrum of CBRN threat environments: the EXOSKIN-S1 low-weight (4.4lbs), low-burden system for lower risk operations, and the EXOSKIN-S2, which offers a protection profile tailored toward operations with higher threat levels.

EXOSKIN-S2 leverages an advanced Avon Protection design that utilizes an activated carbon fabric (ACF) inner layer for enhanced protection against aerosol threats, vapor, liquid and particulate chemical warfare agents (CWAs). Combined with a low-noise emitting outer layer, the suit provides improved protection for operations in CBRN environments of up to 24-hour duration for longer time in the field.

EXOSKIN-S2 retains the ‘suit as a system’ ensemble design of the original EXOSKIN-S1 suit with its focus on seamless integration with essential CBRN protective equipment, including Avon Protection respirators, EXOSKIN-B1 boots and EXOSKIN-G1 gloves. Key enablers include an integrated hood with double elasticated aperture that ensures a protective seal around the respirator, maximizing protection without restricting movement. It also features hook and loop adjustable tabs on the lower legs, a thumb loop and inner leg gaiter with stirrup to prevent ingress when worn.

Other common design elements across the EXOSKIN suit range include a quarter zip and full zip options with hook and loop fastening for improved integration with body armor; and multiple outer fabric pattern and color design formulations to minimize user detection in hostile environments.

“Our EXOSKIN range has been designed to protect operators from CBRN threats while reducing the physiological burden, so they stay more comfortable for longer,” Steve Elwell, President, Avon Protection, said. “With EXOSKIN-S2, we are giving users a greater choice of protection levels and continuing to deliver the Avon Protection quality assurance they know and trust to keep their operators safe in demanding environments.”